By Barbara R. Blackburn

Instructional rigor is a key component of effective instruction. Too often we think that our instruction is rigorous, but oftentimes it is not. Our assumptions about rigor, as well as our practices, make a difference in what we expect from students.

Instructional rigor is a key component of effective instruction. Too often we think that our instruction is rigorous, but oftentimes it is not. Our assumptions about rigor, as well as our practices, make a difference in what we expect from students.

One of the biggest misconceptions about rigor is that scaffolding should not be a part of rigor. In fact, scaffolding is a core part of rigorous instruction. The higher the level of rigor, the higher the need for support.

Defining Rigor

In Rigor is Not a Four Letter Word, I define rigor as creating an environment in which:

- Each student is expected to learn at high levels.

- Each student is supported so he or she can learn at high levels.

- Each student demonstrates learning at high levels.

Notice we are looking at the environment you create. The tri-fold approach to rigor is not limited to the curriculum students are expected to learn. It is more than a specific lesson or instructional strategy. It is deeper than what a student says or does in response to a lesson.

True rigor is the result of weaving together all elements of schooling to raise students to higher levels of learning. Scaffolding is an integral part of the definition. It’s simply not right to set a high bar and expect students to get there without support and scaffolding. Rigor and scaffolding are only effective in partnership.

Providing additional scaffolding throughout lessons is one of the most important ways to support your students. Oftentimes students have the ability or knowledge to accomplish a task, but are overwhelmed at the complexity of it and get lost in the process. This can occur in a variety of ways, but it requires that teachers ask themselves during every step of their lessons, “What extra support might my students need?”

Scaffolding: A Critical Component of Rigor

Support and scaffolding are critical for student success. However, I’ve found that scaffolding can be misunderstood. For example, when I was a student, if someone needed help, they were pulled out of class, put in a corner, and given extra worksheets to do. I have no idea if the level or the practice was appropriate. One of the lessons I learned was to never ask for extra help.

Much later, as a consultant, I was visiting a high-poverty school that was struggling with test scores. I was leading an evaluation team designed to provide feedback to the teachers. I visited a science classroom and noticed that some students were working on an informational sheet about plants. When a student asked for help, they were given an alternate sheet that simply required them to color the plant. When the team met, we realized that was the major scaffolding strategy: coloring.

Much later, as a consultant, I was visiting a high-poverty school that was struggling with test scores. I was leading an evaluation team designed to provide feedback to the teachers. I visited a science classroom and noticed that some students were working on an informational sheet about plants. When a student asked for help, they were given an alternate sheet that simply required them to color the plant. When the team met, we realized that was the major scaffolding strategy: coloring.

When a student is struggling to learn, they need assistance. B K. Garner in Getting to Got It points out that students use cognitive structures to process information and create meaning in these four ways:

- Making connections

- Finding patterns

- Identifying rules

- Abstracting principles

Struggling learners are having difficulty in one or more areas. Our role is to help them process information properly and create meaning that is correct and that makes sense.

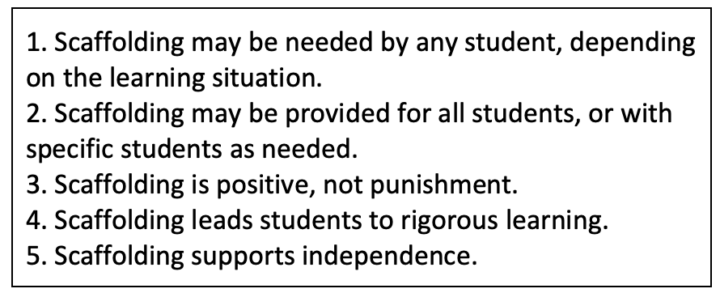

My 5 Beliefs About Scaffolding

►1. Scaffolding may be needed by any student, depending on the learning situation.

First, I’ve found that scaffolding may be needed by any student. For example, when I was a professor at a university, I taught graduate students – teachers working on a master’s degree. You might think they wouldn’t need any extra help; after all, they had made it this far. However, I taught an advanced research paper that was unlike anything they had written before. Because of this, they needed scaffolding for the assignment. I broke it down into chunks, modelled the type of writing, and led writing conferences for feedback. One of my students said, “I didn’t think I needed help, but I wouldn’t have been successful without it.”

It’s easy to identify students who regularly struggle. It’s less so when you have honors students who are struggling and hiding their needs. Part of effective instruction is identifying all students who need help.

►2. Scaffolding may be provided for all students, or with specific students as needed.

Second, scaffolding may be needed for your entire class, such as in the example with my graduate students above, or with certain students. The art of scaffolding is determining what scaffolding is needed, but also who needs it. If you are teaching a new or complex strategy, you may need to use some standard scaffolding skills with all students to ensure success. However, you will have times where a small number of students need additional scaffolding. Both are appropriate.

►3. Scaffolding is positive, not punishment.

Oftentimes, students are afraid of asking for help. They may be ashamed, or they may not want other students to laugh at them. It is part of our job as teachers to help students understand that needing and accepting help is a normal part of the learning process. When we “make” them stay after school without offering other options, students view scaffolding as punishment. When we give students pages of extra practice, students view scaffolding as punishment. Let’s create scaffolding opportunities that students see as positive and supportive.

►4. Scaffolding leads students to rigorous learning.

Effective scaffolding always leads students to rigorous learning. When we make a decision to simply “dumb things down” so students can be successful, we are depriving them of the opportunity to learn at high levels. For example, simply giving students something easier to read may help them feel good, but using a process where students read an easier text, then move back to something more complex once they have built background knowledge and vocabulary, allows them to succeed at a more rigorous level.

►5. Scaffolding supports independence.

Finally, scaffolding supports independence. Sometimes, perhaps unintentionally, we provide support in a way that encourages students to become dependent on us. They can develop learned helplessness, a set of learned skills where students don’t even try on their own – they simply wait and look to us for answers. This is not what we want for our students. We want to provide the scaffolding, lessen it over time, and encourage students to try more and more on their own.

A Final Note

It’s important to recognize that scaffolding is an integral part of rigor. Students will rise to the level of high expectations, but they may need support and scaffolding to achieve the goal. Understanding beliefs about rigor and how this applies to your classroom is critical.

Find scaffolding tools and supports at

the Scaffolding for Success book page.

Dr. Barbara R. Blackburn, a “Top 10 Global Guru in Education,” is a bestselling author of over 30 books and a sought-after consultant. She was an award-winning professor at Winthrop University and has taught students of all ages. In addition to speaking at conferences worldwide, she regularly presents virtual and on-site workshops for teachers and administrators.

Dr. Barbara R. Blackburn, a “Top 10 Global Guru in Education,” is a bestselling author of over 30 books and a sought-after consultant. She was an award-winning professor at Winthrop University and has taught students of all ages. In addition to speaking at conferences worldwide, she regularly presents virtual and on-site workshops for teachers and administrators.

Barbara is the author of Scaffolding for Success (Routledge/Eye On Education, 2025) and many other books and articles about teaching and leadership. Visit her website and see some of her most popular MiddleWeb articles about effective teaching and support for new teachers here.

Feature image by LeDecodeur from Pixabay