Based on the insights gleaned from TNOC Festival, future research in urban ecology could benefit from multispecies urbanism, which emphasizes the integration of diverse species into city planning to enhance biodiversity and ecosystem services.

I recently attended The Nature of Cities Festival (TNOC Festival) in Berlin, Germany, where I hosted a session with colleagues on the Global Roadmap for the Nature-based solutions for Urban Resilience in the Anthropocene (NATURA), a National Science Foundation research initiative co-led by the Urban Systems Lab. TNOC Festival uniquely blends elements of a conference, art exhibition, and retreat, all centered on urban nature. This year, it was held at Atelier Gardens, a former hub of German filmmaking now repurposed as an event space. The philosophy of Atelier Gardens focuses on soil, soul, and society, integrating natural, social, and spiritual elements. This ethos matched the essence of the TNOC festival, promoting an inter- and transdisciplinary exchange and offering new experiences in the field of urban ecology.

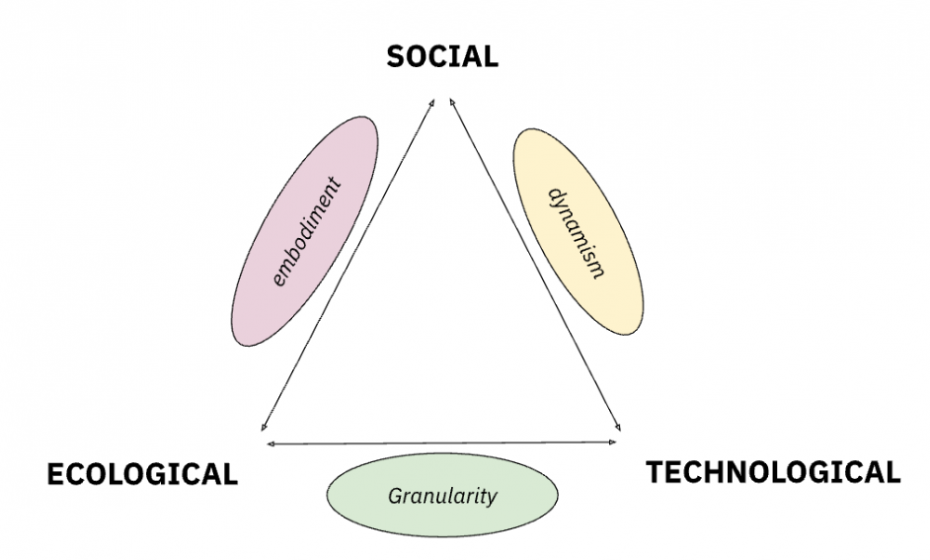

Three key themes — granularity, dynamism, and embodiment — which emerged from the sessions I attended, are each highly relevant to my work at the Urban Systems Lab and on the NATURA Global Roadmap.

The themes illuminate the complex interactions between social, ecological, and technological components in urban environments, and in this blog, I explore how they connect to three compelling TNOC Festival sessions:

I contend that these themes are crucial for advancing urban nature research, as they fill knowledge gaps and re-invigorate researchers, and align comprehensively with the social-ecological-technological systems (SETS) framework. By examining urban landscapes through these lenses, researchers can gain a more nuanced understanding of the intricate relationships shaping our cities and their natural elements.

The NATURA Global Roadmap and Social, Ecological, Technological Systems (SETs)

The NATURA Global Roadmap (GRM) is a groundbreaking initiative to synthesize knowledge and identify gaps in urban nature-based solutions (NbS) across academia and practice. By leveraging insights from NbS implementation in seven world regions, the GRM aims to create a comprehensive understanding of global urban sustainability efforts. This multi-faceted project will culminate in a global report and seven regional assessments on the state of urban NBS, slated for release in early 2025. Given the project’s scope and complexity, careful attention must be paid to granularity, dynamism, and embodiment throughout its execution.

One of the most helpful ways to contextualize this urban nature research is through a social, ecological, and technological systems framework (SETS), to measure the interactions between people, nature, and infrastructures. Similar to the Atelier Gardens model of soil, soul, and society, a SETS framework allows a holistic understanding of urban nature systems. In this context I argue that embodiment falls under a social-ecological interaction, dynamism as a social-technological interaction, and granularity as a technological-ecological system.

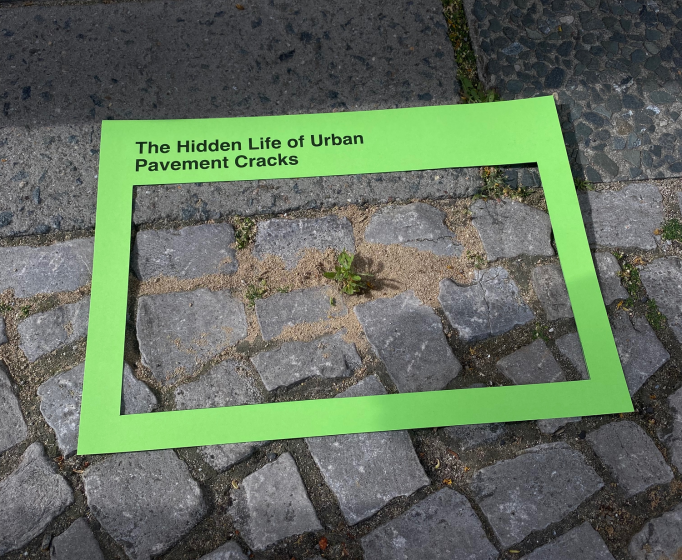

The Hidden Life of Urban Pavement Cracks

The Global Roadmap is interested in a variety of scales – including global, regional, national, city-wide, and site. What is difficult to focus on in a project of this size is the micro-ecosystem. The micro-ecosystem is the heart of the work that Dr. Sophie Lokatis and Susanne Weiland presented during their session “The Hidden Life of Urban Pavement Cracks.” They showed the resilient biodiversity that exists in urban pavement cracks, how it changes throughout the seasons, and the importance of this habitat for ground bees and wasps.

Weiland began the session by describing her masters project in which she documented the biodiversity of one pavement crack in London for six months. She discovered how riverine plants grow in the rainy months when the cracks are underwater for days at a time, and coastal plants grow in the drier season made possible by the salt spread on sidewalks during the winter to melt snow. She used this tiny cycle to show the resiliency and cohabitation of urban plants, even on the smallest scale.

Dr. Sophie Lokatis described her background in entomology that led to a project of documenting ground bees and wasps living in pavement cracks in urban areas. She showed the participants how to spot nests and how she captures and studies these incredible pollinators. Together they are part of an inaturalist project that encourages people to document urban pavement crack biodiversity all over the world.

Granularity and Technological-Ecological Systems in Urban Ecology

Granularity in urban nature research is crucial for understanding and managing the complex interplay between technological and ecological systems. By examining urban ecosystems at fine scales, researchers can uncover detailed insights into the biodiversity and ecological processes that occur in the smallest niches, such as pavement cracks. This level of detail is often overlooked in broader-scale studies but is essential for a comprehensive understanding of urban ecology. Granularity in research can also enhance the ability to develop targeted restoration and conservation strategies. Understanding the specific needs and habitats of species like ground bees and wasps can inform urban planning and green infrastructure development. This integration of technological and ecological systems ensures that urban environments can support diverse and resilient ecosystems even in the face of urbanization and climate change.

Architecture as Trees

During the first day’s plenary, Ferdinand Ludwig discussed his work on “living structures” inspired by living root bridges created and maintained by the Khasi in Eastern India. These bridges are fashioned using the aerial roots of rubber fig trees. As the aerial roots grow, the Khasi manipulate the roots to grow together by tying them and supporting the structures with wood or bamboo. These bridges can grow into constructions that hold up to 50 people and last for hundreds of years if maintained properly.

Ludwig was inspired by this process for his work in Germany on baubotanik or “living plant constructions.” Baubotanik is a building method of creating architectural structures through the interactions between technical joints and plant growth. Ludwig emphasizes the dynamics of this architecture, as hundreds of young plants fuse around a metal structure forming a “hyper-organism” that is constantly changing. This process challenges the idea that urban architecture projects have a finish date – that there is always room for growth and evolution.

Dynamism and Social Technological Systems in Urban Ecology

The concept of dynamism runs through Ludwig’s work and parallels the granularity in urban nature research by highlighting the ever-changing nature of urban ecosystems. Just as baubotanik structures evolve and adapt over time, urban ecosystems at micro scales, such as pavement cracks, are also dynamic and resilient. This dynamism is intrinsic to social technological systems, where human interventions and natural processes intertwine to create sustainable urban environments.

By embracing the dynamism and granularity of urban nature, researchers and planners can foster urban spaces that are not only biodiverse but also adaptable and resilient. This approach acknowledges that urban ecosystems are living systems, continually influenced by both technological advancements and ecological interactions. Thus, integrating granular research and dynamic living structures into urban planning can lead to more sustainable and innovative solutions for urban development.

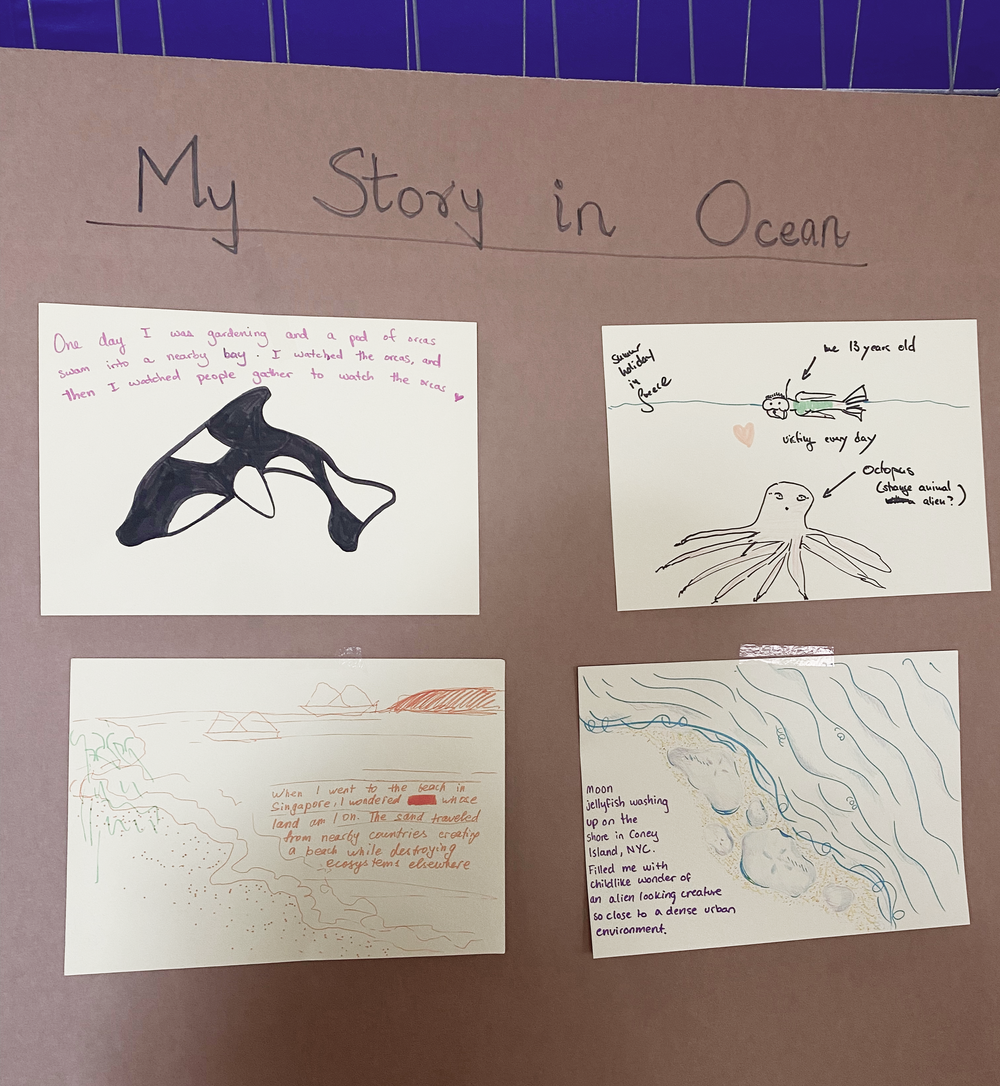

Exploring the Power of Stories and Art for Understanding Diverse Perspectives on Nature-based Solutions

This session, run by Vanya Bisht, Mariana Hernández, and Danielle MacCarthy, invited participants to share personal stories about nature in four different urban ecosystem types: forest, urban core, river, and ocean. Using storytelling and drawing, participants expressed their experiences and visions for these ecosystems.

I was a part of the ocean group, where we explored how to redefine the concept of a beautiful beach. I drew a picture of moon jellyfish washing up on Coney Island shores, reminiscent of my childhood fascination with such an alien creature appearing in the midst of a dense urban environment. It caused me to think more deeply about my access to shorelines as a child and what felt special about the experience.

These narratives then informed a collaborative plan for what these urban ecosystems could look like in 2040 through the conceptualization and implementation of Nature-based Solutions. Instead of only imagining crystal clear waters and golden sands, we considered finding recreational joy in rocky or seaweed-filled beaches. This reimagining supports dune and mangrove restoration, which are vital for biodiversity and erosion protection, and reduces the carbon footprint associated with importing sand for “golden beach” aesthetic purposes. We also discussed the importance of access to waterways, drawing from experiences of limited water access in many areas of New York City, emphasizing the social component of urban coastlines.

Embodiment and the Social-Ecological System

The session highlighted the concept of embodiment, where personal interactions with nature are expressed and integrated into the planning of urban ecosystems. Embodiment in this context refers to the physical and emotional experiences individuals have with their environment, which are crucial in shaping their connection to urban nature. By sharing stories and creating drawings, participants physically engaged with their memories and perceptions of nature, embodying their experiences in a tangible form.

This embodiment creates a social-ecological system where human experiences and natural elements are interwoven. Personal stories and creative expressions become part of the broader ecological narrative, influencing how urban ecosystems are conceptualized and designed. The social aspect is evident as participants’ collective experiences and insights contribute to a shared vision for future urban environments, emphasizing the interconnectedness of social and ecological systems. By incorporating these embodied experiences into urban planning, we can create more inclusive and responsive urban ecosystems. This approach ensures that the design of urban spaces reflects the diverse ways people interact with nature, fostering environments that support both ecological resilience and social well-being.

Furthermore, this process of sharing and embodying personal experiences is vital for inspiring researchers. It provides them with rich, qualitative data and insights that might not emerge from traditional scientific methods alone. Engaging with the lived experiences of individuals helps researchers to appreciate the nuanced and multifaceted relationships people have with urban nature, driving innovative and empathetic approaches in their work. By connecting on a human level, researchers can develop a deeper understanding of the social dimensions of urban ecology, ultimately enhancing the impact and relevance of their research. Thus, the session not only redefined the aesthetics of urban nature but also reinforced the importance of integrating human experiences into the ecological fabric of cities, inspiring researchers to consider the holistic and dynamic nature of urban ecosystems.

Conclusion

The Nature of Cities Festival in Berlin provided a dynamic platform to explore urban nature’s multifaceted dimensions. Granularity emphasized the importance of fine-scale research in urban ecosystems; dynamism highlighted the evolving nature of urban environments; and embodiment incorporated personal experiences and emotional connections with nature into urban planning. The festival showcased interdisciplinary exchange, reinforcing the necessity of a SETS framework in urban nature research to promote resilient, inclusive, and vibrant urban ecosystems worldwide.

Based on the insights gleaned from the festival, future research in urban ecology could benefit from multispecies urbanism, which emphasizes the integration of diverse species into city planning to enhance biodiversity and ecosystem services. City planners can apply these insights by designing urban spaces that accommodate various species’ needs, promoting coexistence between humans and wildlife at multiple scales. This approach can lead to healthier, more resilient urban environments. Additionally, emerging technologies such as remote sensing, environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis, and Artificial intelligence-backed climate modeling will enable more precise monitoring and management of urban ecosystems. These innovative methods and interdisciplinary collaborations will be crucial in advancing our understanding and implementation of nature-based solutions in urban settings.

Natalie Pierson

New York City

Originally posted on Urban Systems Lab blog.

References

“Ferdinand Ludwig’s Schedule for TNOC Festival 2024.” n.d. Accessed July 9, 2024. https://tnocfestival2024.sched.com/artist/ferdinand.ludwig.

Ludwig, Ferdinand. 2022. “Baubotanik.” 2022. https://www.arc.ed.tum.de/gtla/forschung/baubotanik/.

McPhearson, Timon, Elizabeth M. Cook, Marta Berbés-Blázquez, Chingwen Cheng, Nancy B. Grimm, Erik Andersson, Olga Barbosa, et al. 2022. “A Social-Ecological-Technological Systems Framework for Urban Ecosystem Services.” One Earth 5 (5): 505–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2022.04.007.

“NBS Global Roadmap.” n.d. NATURA. Accessed July 9, 2024. https://natura-net.org/nbs-global-roadmap.

“The Hidden Life of Urban Pavements Cracks · iNaturalist.” n.d. Accessed July 9, 2024. https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/the-hidden-life-of-urban-pavements-cracks.

“TNOC Festival 2024: Exploring the Power of Stories and Art f…” n.d. Accessed July 9, 2024. https://tnocfestival2024.sched.com/event/1Z1TT/exploring-the-power-of-stories-and-art-for-understanding-diverse-perspectives-on-nature-based-solutions.

“TNOC Festival 2024: The Hidden Life of Urban Pavement Cracks.” n.d. Accessed July 9, 2024. https://tnocfestival2024.sched.com/event/1Z1Vh/the-hidden-life-of-urban-pavement-cracks.

Wieland, Susanne Elizabeth. 2022. “‘The Hidden Life of a Pavement Crack.’” JAWS: Journal of Arts Writing by Students 8 (Art and Non-Human Agencies): 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaws_00040_1.

About the Writer:

Natalie Pierson

Natalie, a New School graduate in Environmental Studies and Interdisciplinary Science, now serves as Lab Manager at USL. In her current position, Natalie applies this holistic perspective to advance equitable urban practices, bridging scientific inquiry with on-the-ground urban climate adaptation.