about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

Murals are everywhere now—on schoolyards and salt boxes, buses and armories, waterfronts and wildlife refuges. They are declarations made in public, at the scale of daily life. And increasingly, they’re asked to do more than beautify: to cool streets, catalyze coalitions, shift behaviors, and tell a truer story about who “we” are and what futures we’re willing to work for. This roundtable brings together artists, planners, scientists, and civic leaders living inside that question: how can murals be catalysts for climate and community action?

A first theme is the power—and responsibility—of beauty. Kwadwo Adae argues that craft matters: skillful work earns public trust and ignites what he calls a “Contagious Encore Effect,” where one mural begets another and, ideally, trees and other green infrastructure follow. Jane Golden shows how Philadelphia’s practice has evolved from one-off neighborhood works to system-level interventions that literally move people toward greener choices. Here, beauty isn’t a frill; it’s an instrument that invites attention, curiosity, and pride—the preconditions for collective action.

Second, murals as connective tissue. Mark Johnson and Kilia Llano describe murals as living social instruments rather than static images—civic rituals that transform spectators into co-authors. Annie Lin calls mural-making an “OG icebreaker” that convenes officials, residents, businesses, and youth—rooms where climate science alone rarely gets a hearing. In New Haven, that energy has coalesced into “cool murals” blending climate data, reflective paints, and community storytelling—art that doesn’t just symbolize resilience but practices it.

Third, the medium is not neutral. Erika Svendsen foregrounds material choices: cool pigments that reflect heat, mineral binders that root us in earth, coatings that scrub pollution. If the message is in the medium, then the wall can become micro-infrastructure for adaptation. This raises practical questions that recur across essays: How do we specify materials for environmental benefit and durability? Who maintains them over time? How do we measure impact rigorously yet legibly?

Fourth, limits and unintended consequences. Lisa Lee and Tara von Schmidt insist that murals are not policy, nor are they filtration systems, safer streets, or affordable housing. Without links to tangible next steps—volunteering, advocacy, design changes, budget shifts—murals risk becoming decorative conscience. Tara urges vigilance when projects stand in for, rather than support, real change, especially where community voice is light and institutional branding heavy. Lisa’s intersection murals—useful for visibility and safety but subject to fading and regulations—remind us that design lives inside governance.

Fifth, place specificity. Mike Houck’s Portland story shows how a single heron could pull people’s gaze to a neglected wetland and mobilize policy attention toward an urban refuge. Shayna Rose’s Baltimore salt boxes flip humble winter infrastructure into a citywide canvas, seeding a different imagination for streets. In New Haven, Thermal Reflections and Take the Risk to Cool Down anchor conversations about heat, history, and apprenticeship. These are not generic backdrops; they are ecologies of memory, power, and possibility. A catalytic mural reads the room—and the watershed.

Finally, authorship and trust. Michael DeAngelo urges prioritizing excellence in the physical world of public art amid a rush toward disembodied, machine-generated imagery. His point isn’t tool panic; it’s about accountability and craft. If murals are to help us reattach to place, they must be anchored in human skill and lived experience.

From these threads arise the open questions we hope readers will carry forward:

-

What counts as impact, and on what timescale—surface temperatures, transit ridership, canopy growth, or the slower metrics of belonging and civic capacity?

-

Where is the line between catalyst and cover, and what safeguards—shared governance, community commissioning, maintenance funds—keep murals from substituting for policy?

-

How can materials, fabrication, and siting maximize climate benefit while minimizing environmental cost, and what standards help cities scale “cool murals” responsibly?

-

Who decides the story on the wall, and how do authorship, apprenticeship, and compensation reflect local knowledge and histories?

-

If a mural asks “What will you do?”, what proximate, doable actions are available within a five-minute walk of the wall?

Why does this matter now? Because climate change is a hyperlocal, uneven present, and the work of transition won’t happen in spreadsheets alone. It will happen where people can see themselves, bring their kids, meet neighbors, argue a little, learn a little, and leave with a task for tomorrow. Murals excel at staging that kind of public life. Our contributors aren’t offering cure-alls; they’re offering evidence and caution, technique and poetry. They ask us to raise the bar on craft, embed art in coalitions, mind the chemistry, budget for maintenance, measure what matters, and insist that every wall points past itself to a living network of people, policies, and places.

In short: make beauty consequential; turn spectators into stewards; align materials with missions; refuse fig leaves; choose sites that teach; and bind images to invitations—clear steps that let the story on the wall walk into the world.

about the writer

Lisa Lee

Lisa Lee is the Director of Sustainability Programs at EZ Ride, one of New Jersey’s Transportation Management Associations (TMAs). She oversees the statewide EV Accelerator Program and the Bike and Pedestrian Program and encourages schools and communities to implement asphalt art projects, complete and green streets and conducts walk-bike audits, speed studies, and air quality monitoring to improve safety for those who walk and bike, and to reduce air pollution, and global climate change.

Lisa Lee

When possible, we should use art to encourage people to consider our planet and live in a way that reduces global climate change.

Murals in cities can serve as a visual message for all who see and encounter them. Besides being a way to improve the aesthetics of communities or to honor a community leader, they can be a call to action or can remind people of what is occurring and the need to change behavior. In the visual below, the right side of the mural demonstrates the negative impacts of climate change: the dead flowers, dirty ocean water, and wildfires are a powerful reminder that if nothing is done, these consequences will continue. In my view, I think the message could have also included a call to action, such as “What Will You Do?” to remind people that they can make a difference.

It is an important and good idea for more artists to go beyond the beautiful images they create to intentionally make their art a powerful statement and message for people in cities. Many artists create murals to honor local activists for their contributions or to improve community aesthetics. Murals that also convey a message can increase their effectiveness and help achieve a goal beyond making the community more attractive.

There are numerous issues that people in cities face, including crime, traffic safety concerns, poverty, hunger, and a lack of affordable housing. In my role, trying to make communities safer and to reduce traffic congestion and emissions and encourage walking or biking as active transportation, we created an intersection mural in the City of Passaic at an intersection where a few pedestrians and cyclists were struck and injured by traffic. The mural included a painting of ladies dancing in the center by a local student. Unfortunately, the high amount of traffic on this roadway caused the center artwork to fade quickly. The mural also included painted curb extensions and plastic delineators to prevent illegal parking on street corners and improve pedestrian visibility.

We also painted striped, high-visibility crosswalks to make them more visible to drivers and had the City repaint the stop bars and yellow curbs to let drivers know that parking by the curbs is illegal. The curb extensions also play a role in shortening the crosswalks, which is helpful for seniors and children who walk slower. The extensions feature traditional Mexican and Puerto Rican foods, Pozole and Mofongo, and bongo drums and cuatros from the dominant Latino culture in the city. Due to MUTCD regulations, written messages are not permitted on roads as it may be distracting to drivers, but a sign can be placed to explain the point of the art for residents.

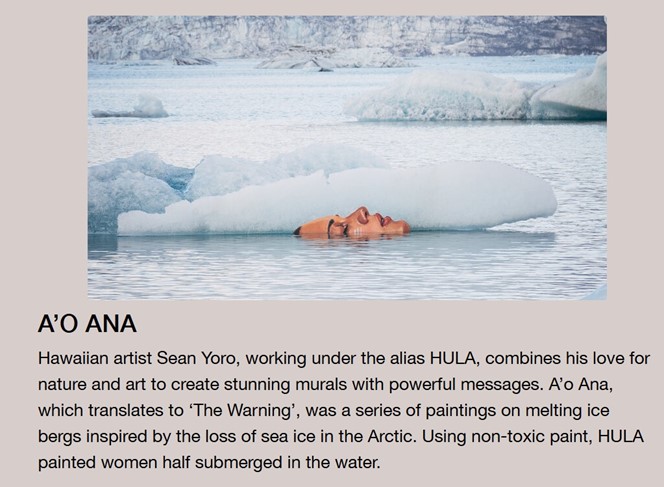

The mural below, made by a local Hawaiian artist, shows a woman being submerged in the ocean. The visual draws attention to the impacts of the melting icebergs but lacks a written message and loses an opportunity to emphasize the artist’s point that the loss of sea ice will affect society.

I would encourage artists and environmental advocates to use community art installations to emphasize important messages that can motivate the community to take steps to reduce our impact on climate and the environment. We can remind people to drive less and bike & walk more, or use transit to reduce transportation emissions. When possible, we should use art to encourage people to consider our planet and live in a way that reduces global climate change.

Tara von Schmidt

When that is linked to actual action, then one day a mural reaches beyond art on a wall and becomes part of a living thing.

Murals are often talked about as powerful catalysts for change—and they can be. They transform blank walls into places where stories are told and conversations begin. Sometimes, just one image on a building can catch someone’s eye in a way charts or news articles never could. Murals can really do a good job of rendering complex matters—like rising sea levels or disappearing species—very personal and intimate. Artful transformation of science is a rare kind of magic: public art does exactly that.

That said, I think we need to be honest about the limits of murals, especially when it comes to climate action and community impact. A mural does not automatically move change. And its impact hinges on the way in which it’s produced, who’s involved, and what comes after. Beautiful or not, a climate-themed mural that doesn’t connect to real opportunities—volunteering, advocacy, or minor behavioral changes —threatens to turn into a simply pleasant thing to glance at. It can be noticed for a second, then quickly disappears into the hum of everyday life.

There’s also this tricky place where murals begin to function in the place of real change. They enhance a neighborhood’s appearance and create a sense of progress—and that absolutely has worth. But a mural about clean air doesn’t clean the air and a mural about equity doesn’t fix policy. And when such works are commissioned by institutions or developers without community involvement, they often begin to appear more like cover-up than dialogue. Here’s a way of saying “look, we care”: while not doing much to prove it.

There comes then the question of who’s getting represented. When murals do not reflect the people who live in a community, they often miss the point. If it’s not a message or picture that reflects local voices, people cannot resonate. And when the ones trying to come up with the artist or the theme don’t represent that community, there’s already a disconnect present in the project. Rightly, people want to be seen and heard in their own community.

Yet, murals can have meaningful value. They occupy this neat space between awareness and action. When they’re co-created purposefully and in service of something larger than themselves, they have the potential to bring real momentum in climate action and awareness. A mural has real power, but that doesn’t mean having the right paint or the right wall, it means what gets built after it; the conversations, the partnerships, the connections that come from it.

So, I wouldn’t say that murals don’t contribute to climate awareness. I would say it’s how we wield them. A mural can’t fix a system alone, but it can brace the work that does. It can provide an opportunity for reflection, a moment of pride or just a reminder that something matters here. And when that is linked to actual action, then one day a mural reaches beyond art on a wall and becomes part of a living thing.

about the writer

Jane Golden

Jane Golden has been the driving force of Mural Arts Philadelphia since its inception, overseeing its growth from a small city agency into the nation’s largest public art program. Under her direction, Mural Arts has created over 4,000 works of transformative public art. In partnership with innovative collaborators, she has developed groundbreaking and rigorous programs that employ the power of art to transform practice and policies related to youth education, restorative justice, environmental justice and behavioral health. Golden currently serves on the Mayor’s “Clean and Green” Initiative cabinet, and as Critic-in-Residence at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

Jane Golden

The Transformative Power of Murals

For over four decades, Mural Arts has been at the forefront of creating murals that not only beautify neighborhoods but also generate memorable, cohesive, and sometimes even magical experiences.

For over four decades, Mural Arts has been at the forefront of creating murals that not only beautify neighborhoods but also generate memorable, cohesive, and sometimes even magical experiences. These projects have been instrumental in changing attitudes and behaviors within communities. In the early years, the focus was on episodic efforts—individual projects that highlighted a single community’s histories and heroes. These murals brought vibrancy and pride to neighborhoods while providing technical and team-building skills to former graffiti writers and apprentices, expanding their portfolios and creative ambitions.

From Neighborhood Beautification to Systemic Change

As Mural Arts’ work expanded into new sites and systems, the ambitions and challenges grew more complex. The organization was called upon to transform neighborhoods with vacant lots and to turn tagged and graffitied schoolyards into dynamic history lessons. One of the early mobile initiatives was the “Design in Motion” project, launched in 2009 and 2010. This effort involved creating a fleet of 20 multi-colored, exuberantly designed recycling trucks. Led by artist Desireé Bender and art education students, and in collaboration with Philadelphia University’s Design Center and the Philadelphia Streets Department Recycling Office, “Design in Motion” coincided with the introduction of the city-wide single-stream recycling program.

The trucks, covered in vinyl wraps featuring artwork inspired by textile studies from The Design Center’s now-closed collection, became moving murals throughout Philadelphia. Their dedication was marked by grand parades down Broad Street on Earth Day in 2009 and 2010. Public elementary schools, their teachers, students, and sanitation workers were actively involved in the selection of designs, making the project a shared civic experience. The initiative encouraged Philadelphians to participate in recycling efforts, and it had a lasting impact—students would eagerly watch for the recycling trucks, celebrating both the drivers and themselves as local heroes.

Connecting Communities to Green Spaces

In 2023, “Getting to Green: Routes to Roots”, developed by artists Laura Deutsch and Shira Walinsky, sought to inspire Philadelphia residents to use public transportation to explore the city’s green spaces. The project included unique artwork such as bus wraps featuring images of nature and local monuments, posters in bus shelters, and print materials with hand-drawn maps. These resources encouraged riders to discover new pathways and routes, while short video profiles shared the personal stories of riders, drivers, and the routes themselves.

A key focus of the project was to promote equity in public transportation by engaging immigrant, refugee, and non-native English-speaking communities. By facilitating access and understanding of the bus system, the project encouraged these communities to venture beyond familiar areas and enjoy the city’s natural beauty. Throughout the year, “Getting to Green: Routes to Roots” highlighted transit routes to nature walks, picnic spots, bike paths, and special events, creating opportunities for residents to connect with both their city and its environment.

Note: This project is ongoing.

Looking Ahead: FloatLab at Bartram’s Gardens

Looking to 2026, the FloatLab will be situated along the southern shoreline of Bartram’s Gardens, adjacent to natural tidal wetlands and historic Lenni Lenape sites. Designed by Höweler + Yoon Architecture, the FloatLab is an ADA-compliant, sloped circular platform that invites visitors to engage with the Schuylkill River at eye level. This unique structure is intentionally multi-valent and multi-functional—serving as a platform, vessel, lens, and threshold for meaningful and unprecedented public engagement with the river’s ecology.

The FloatLab will reconnect Philadelphians and visitors with their natural environment and the historic Bartram’s Gardens site, fostering new relationships between the site and nearby immigrant and working-class communities. The higher portion of the loop can accommodate a full classroom or arts audience, while the sloping ramp enables visitors to connect with the river in their own way—be it collecting water samples, painting outdoors, exploring floating gardens or freshwater mussel beds, or simply spending time reflecting on the living, tidal river that has sustained life for thousands of years.

about the writer

Shayna Rose

Shayna Rose is the Toward Zero Planner for the Baltimore City Department of Transportation. In her role, Shayna analyzes high-injury roadways and intersections and identifies systemic interventions to improve traffic safety at these locations, using a transportation design approach that centers pedestrians, bicyclists, and other vulnerable roadway-users.

Shayna Rose

How can murals be catalysts for climate and community action?

Every time one of these placemaking projects is installed, I imagine that it inspires several new people to dream up alternative visions for their own streets.

Baltimore is a supremely creative city. Home to the renowned Maryland Institute College of the Arts, offering a shockingly low cost of living, and benefitting from easy access to major cities along the Northeast Corridor, Baltimore has long been attractive to artists.

When you live in a city of artists, everything is a canvas. We have bountiful murals on public and private structures and on just about every sort of vertical surface you can imagine―walls, bridge columns, railings, and more―that depict neighborhood life, folk legends, local historical figures, national heroes, and abstract concepts. The latest and most popular canvas is our municipal salt boxes, a type of public service infrastructure that is unique to Baltimore. While the Baltimore City Department of Transportation takes care of salting the major roads, BCDOT distributes yellow wooden boxes filled with salt to neighborhoods so that Baltimoreans can tend to their own blocks of minor streets and sidewalks. In 2020, local artist Juliet Ames decided to decorate one―a simple bedazzled spruce-up of the typical black, boxy “SALT BOX” letters. Her act of small-scale muraling spurred a citywide phenomenon, prompting artists and everyday residents alike to enliven salt boxes in their neighborhoods. The artistic salt box became an official BCDOT program, allowing artists to secure artwork to the boxes at the beginning of the snow season and remove it at the end, and it remains an extremely popular way to add whimsy and cultural commentary to the public realm.

The artistic salt box is a prime example of how art can inspire people to reconsider the mundanity of everyday life, which in turn can inspire action. Before I became a transportation planner, like everyone else, I would walk down a street and listen to my music or call my mom without contemplating that a street could be anything other than it is. Now, it is second nature for me to look at a wide, multi-lane, high-speed street and imagine an entirely different setting ―one with a streetcar, a wide bicycle lane protected by vegetation, new tree cover, expanded sidewalks with plentiful public seating, and maybe just one car lane instead of five. My vision is for the angrily revving engines, blaring car horns, and air heavy with exhaust and tire microplastics to be replaced by the gentle clinks of changing gear chains, peaceful chatter, clean air, and the occasional whoosh of a bus going by. Maddeningly, I see this vision on every street I encounter, and it consumes me; it’s elusive, but I can feel it right at my fingertips. In their own way, the prevalence of salt boxes as an example of artistic community placemaking makes this vision feel just a bit more within reach.

As in many cities across the country, art that enhances roadway infrastructure is increasing in popularity in Baltimore. Each year, we have more murals inside intersection curb extensions, sidewalk wayfinding, and creative outdoor seating structures that replace parking. My favorite was a skate ramp placed in a parking spot outside of a tattoo shop in my own neighborhood (it unfortunately is no longer in place after it was destroyed by a reckless driver). Every time one of these placemaking projects is installed, I imagine that it inspires several new people to dream up alternative visions for their own streets. Some of those people may go on to do their own placemaking projects or become so consumed by the possibility of what a street could be that they get involved in transportation advocacy. The pace of change can feel slow, but I like to think that with these kinds of installations increasing exponentially each year, the groundswell of appetite for transformation is inevitable.

about the writer

Mike Houck

Mike Houck, co-founder of TNOC engages urban nature conservation, land use planning, green infrastructure advocacy. He founded the Urban Greenspaces Institute whose motto is “In Livable Cities is Preservation of the Wild” reflecting the belief that without creating livable and loveable cities it will be impossible to protect “pristine” areas outside the city. To be livable and loveable people must have access to nature where they live, work and play. He co-edited Wild in the City, A Guide to Portland’s Natural Areas (2000) and Wild in the City, Exploring The Intertwine (2011) and The Routledge Handbook of Urban Ecology (2011).

Mike Houck

Ugly Building, Threatened Wetland? Put A Bird On It!

What had begun as a beautification project had become an artful tool that piqued enough interest to attract more resources to restore and manage the city’s first official urban wildlife refuge.

My relationship with the 160-acre wetland dates back more than 50 years, a relationship that began with imploring city leaders to designate it as an urban wildlife refuge. Then, over a few pints, our always colorful mayor, Bud Clark―who revered the herons―designated it as the city bird. Inspired by Bud’s action poet laureate, William Stafford, wrote Spirit of Place*, perfectly capturing the city’s ethos toward nature.

How to use those actions to advocate for better management and public involvement to protect and manage the newly designated Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge? A brilliant Blitz Weinhard beer bottle mural ad on a shabby brick wall inspired me to think a galactically huge image of a heron on an equally shabby wall might do the trick. I left a cryptic note on the muralist’s desk: “Love your mural, willing to do a heron”? Serendipitously, ArtFx muralist Mark Bennett’s house faced the refuge. He had long mused about “muralizing” that “butt-ugly” building.

A medical illustrator created the watercolor; scaffolding came from a local resident; a local paint store donated paint; and I kicked in $1,500 to hire a fine art assistant. Soon, the gray monolith was brightened by a 70-foot-tall, stately Great Blue Heron. People who had previously raced by the wetlands stopped, gawking at the massive artwork. For many passersby, it was the first time they stopped, watching herons swallowing huge carp or carting them off to the nearby nesting colony; spying arrays of diving and dabbling waterfowl, and gasping as they saw osprey and eagles dragging carp from the muddy shallows.

What had begun as a beautification project had become an artful tool that piqued enough interest to attract more resources to restore and manage the city’s first official urban wildlife refuge.

Twenty years later, Bennett called me, asking, “Houck, when are we going to finish that building?”. The heron occupied only one of eight on the mausoleum’s gray walls. Asking what it would cost me, Bennet replied, $35,000. At market rate, it would have cost $185,000. Gulping, I realized it would likely take even more and major public involvement effort to accomplish what would be a gargantuan mural.

Even more formidable challenges lie ahead. I needed buy-in from the neighborhood, the building’s new owners’ permission, and, most importantly, I needed the Arts and Culture Council’s Public Art Murals Program blessing. I could hardly complain, given that the purpose for creating the mural wasn’t merely to beautify an ugly building but to bring public attention and involvement to care for the wetlands. I needed to weave together the permits and permissions, raise $75,000, and create a design that would celebrate the biodiverse wetland as a green oasis for nature and people within a short paddle to the city’s urban core.

Shane, Mark’s son, had to grind off thousands of tiny rebar to allow access to the walls; each wall was power washed; He projected photos I gave him onto sheets of paper, tracing each with an electric pen that burned holes in the paper; laid paper grids on the wall and rubbed charcoal, leaving faint outlines of each critter, a process not unlike the paper cartoons Michaelangelo used in the Sistine Chapel.

He and his assistant then painted exquisitely detailed herons, egrets, hawks, hummingbirds, and dragonflies. The result―a stunning 55,000 ft.² wetland mosaic. As with the earlier heron mural, cyclists, runners, walkers, and entire families lingered on the trail, awestruck at the artwork and enjoying the diverse wildlife they previously had raced by.

* Spirit of Place: Great Blue Heron

Out of their loneliness for each other

two reeds, or maybe two shadows, lurch

forward and become suddenly a life

lifted from dawn or the rain. It is

the wilderness come back again, a lagoon

with our city reflected in its eye.

We live by faith in such presences.

It is a test for us, that thin

but real, undulating figure that promises,

“if you keep faith I will exist

at the edge, where your vision joins

the sunlight and the rain: heads in the light,

feet that go down in the mud where the truth is.”

William Stafford, 1987

More Resources:

Article Portland Monthly: https://www.pdxmonthly.com/travel-and-outdoors/2016/05/yes-portland-has-an-official-bird-like-for-30-years-now

Colleen Murphy-Dunning & Ian French

about the writer

Colleen Murphy-Dunning

Colleen Murphy-Dunning is Executive Director of both the Hixon Center for Urban Sustainability and the Urban Resources Initiative (URI) at the Yale School of Environment (YSE). URI carries out community-driven urban forestry to improve both the social and physical environment of the City of New Haven.

about the writer

Ian French

Ian French is the Director of Communications and External Relations at the Hixon Center for Urban Sustainability. He holds a Bachelor of Science (BS) from Yale-NUS College in Singapore, and a Master of Environmental Management (MEM) from the Yale School of the Environment. Ian believes that cities are the crucial unit for addressing the climate crisis, and he finds hope in equitable science-backed solutions that revitalize ecosystems while centering communities.

While science tells us why action is needed, murals show us what we’re fighting for and who we’re fighting with.

Urban areas like New Haven are disproportionately affected by the impacts of climate change. With 85% of local residents at risk of experiencing extreme heat, there is an urgent need for both climate mitigation and adaptation strategies that are accessible to all. Here and elsewhere, murals are not just art. They are tools for urban climate resilience.

Take New Haven’s growing “cool mural” movement, which represents a unique blend of climate science, artistic expression, and community engagement. Cooling murals use heat-reflective paint and design techniques to lower surface temperatures, making them both visually striking and functionally impactful. But beyond their physical cooling effects, these murals ignite something deeper: collective empowerment and ownership of climate solutions.

Two cooling murals were completed in New Haven in 2023 and 2024, demonstrating what is possible when art and science intersect. These murals resulted from a partnership between the Yale School of Art, Yale School of the Environment, Yale School of Architecture, the New Haven Department of Arts, Culture, and Tourism, and community members. Located in Fair Haven, Take the Risk to Cool Down is a vibrant mural by Yale School of Art alum Victoria Martinez (MFA ’20), created in collaboration with a team of Yale artists and climate communicators. Installed outside MATCH, a community manufacturing hub, the mural combines artistic expression with climate action. Inspired by climate data like warming stripes and painted using heat-reflective cooling paint, the piece reduces local heat while spreading awareness about the need for investment in resilient, livable urban spaces.

The second mural, Thermal Reflections, is located on the historic Goffe Street Armory in New Haven’s Dixwell neighborhood and was co-created with the community to reflect local history, climate challenges, and environmental stewardship. Overlooking a community garden by Gather, the design features a red-to-blue gradient symbolizing rising heat and the cooling power of nature. Developed through the city’s first Mural Apprenticeship Program, lead artist Michael DeAngelo trained four local artists in mural-making and cooling paint techniques. Now the city’s largest mural, Thermal Reflections stands as a vibrant symbol of community healing and climate engagement.

Building on this momentum, a third cooling mural is underway at Betsy Ross Arts & Design Academy. Led by recent Yale graduate Haejin Park and supported by the Hixon Center for Urban Sustainability, Urban Resources Initiative, and the City of New Haven, the mural will transform the school’s basketball court. Through design workshops, students have helped shape the mural’s message of hope and resilience, becoming co-creators of the space they play in each day.

When community members participate in creating these cool murals, they don’t just contribute to the artwork, they become ambassadors for the message. They become invested. The act of painting together creates space for dialogue, reflection, and collaboration. And through the creative process, volunteers build a personal connection to the cause, making them more likely to advocate for change long after the paint dries.

When community members participate in creating these cool murals, they don’t just contribute to the artwork, they become ambassadors for the message. They become invested. The act of painting together creates space for dialogue, reflection, and collaboration. And through the creative process, volunteers build a personal connection to the cause, making them more likely to advocate for change long after the paint dries.

This participatory model works because it allows murals to tell a story that people see themselves in. Where science often struggles to connect on an emotional level, art excels. A mural can make passersby stop, look, feel, and think. It can express urgency, hope, and interconnectedness in ways a report or policy memo simply cannot. And when it reflects nature, it taps into biophilia: our innate desire to connect with the natural world.

Art like this makes climate action visible, emotional, and inclusive. While science tells us why action is needed, murals show us what we’re fighting for and who we’re fighting with. In cities facing the front lines of climate change, that kind of movement building is not just powerful; it’s necessary.

about the writer

Annie Lin

Annie Lin (she/her/她) loves to be around artmaking and artmakers. As the Director of Community Engagement and Strategies at the Yale School of Art, Annie explores intersections between community and creativity through partnerships. Annie currently serves on the boards of the International Festival of Arts & Ideas and the New Haven Symphony Orchestra and has a background in U.S.-China arts programming. Annie studied music and education and is passionate about cultural equity as an instrument of change.

Annie Lin

Creating a mural is a powerful, hyperlocal first step toward modeling collective change in your environment.

Alicia Keys calls it a concrete jungle. Architects call it the built environment. My research colleagues call it urbanization. Whatever this man-made thing is, it is ours. When we see the extensive systems our civilization has erected, it is awe-inspiring, but in its sheer scale has now become a threat to our existence.

We’ve built a world that is too big to fail, and now we stand in the chasm between living our lives and confronting the consequences. What can one person possibly do against societal habits that have a real environmental cost? Consider the pureed fruit pouch, a lifesaver in every parent’s lunchbox. It represents just one of the countless dependencies—convenient, seemingly small—that lock us into patterns of consumption that are impossible to disrupt.

Enter a process that, without fail, buoys its participants through shared work and aligned values: mural making. A mural can be the antidote to divisions that segregate our communities. It empowers a neighborhood to publicly declare its values and to demand the attention of all who pass by to pronounce: we will be seen, we will be heard. Delightfully, it is a fun and democratic exercise that anyone can participate in.

As an avid arts administrator, I’ve had the privilege of being part of the mural renaissance in New Haven, a city home to hundreds of public works of art celebrating culture and history. Every time I saw a community mural go up, I saw a space of welcome being created. This is key. So how do we bridge our cutting-edge global climate science with the people who experience its harshest impact?

Mural making breaks the ice. The process forces elected officials, residents, business owners, artists, and activists to come together for a common good. It is so easy to be willfully divided―our modern world almost seems to demand it, to our societal detriment. It is much harder to find the narrow path forward toward collective accountability. Art simply makes it easier. It’s the OG icebreaker. It’s a vehicle for restorative dialogue. If there’s anything I’ve learned from art, it’s that people will rally around something beautiful that changes our perspective―through an aria, an exhibition, or a one-man show about being stuck in an elevator…

Art cannot solve the climate crisis at its core, but it can turn heads. It can bring together rare cross-sections of society to begin a conversation about the shared human condition―a necessary precondition for any collective effort. Dialogue that starts with people in the room can lead anywhere.

about the writer

Kilia Llano

Kilia Llano is a multidisciplinary Dominican artist with more than fifteen years of experience in public art, muralism, and art education. Her practice integrates visual creation with a deep reflection on Caribbean identity, colonial legacies, the denial of Blackness, and the ancestral relationship between humanity and nature.

Kilia Llano

Murals have the power to create moments of pause and reflection in the middle of a busy street or a forgotten wall.

Murals in public space can be powerful catalysts for climate and community action because they operate in the most democratic way possible: they are visible to everyone. You don’t need a ticket, an education, or even a shared language to engage with them. Their visual nature allows them to communicate complex climate issues quickly and emotionally, often more effectively than text or data can. A single image can cross language barriers, connect generations, and evoke feelings of urgency, beauty, grief, and hope all at once.

In the context of the climate crisis—where scientific language can be intimidating or inaccessible—murals speak directly to the heart. They allow people to feel something before they are asked to understand it. There is also a spiritual element to public art that should not be overlooked. Murals have the power to create moments of pause and reflection in the middle of a busy street or a forgotten wall. When they depict elements of nature—oceans, trees, animals, fire, water—they remind us that we are part of something larger than ourselves. This emotional and even spiritual connection to the natural world is essential if we want people to not only care, but act.

In the context of the climate crisis—where scientific language can be intimidating or inaccessible—murals speak directly to the heart. They allow people to feel something before they are asked to understand it. There is also a spiritual element to public art that should not be overlooked. Murals have the power to create moments of pause and reflection in the middle of a busy street or a forgotten wall. When they depict elements of nature—oceans, trees, animals, fire, water—they remind us that we are part of something larger than ourselves. This emotional and even spiritual connection to the natural world is essential if we want people to not only care, but act.

In my own community-based work, I’ve seen how murals can also function as tools for empowerment and collaboration. When local residents, artists, and young people come together to design and paint a mural, the process becomes a form of collective storytelling. The mural is no longer just an image—it is a shared voice, a symbol of presence, resilience, and vision. Of course, murals alone won’t solve the climate crisis. But they can open the door. They can invite people in, generate awareness, spark dialogue, and create a sense of ownership and responsibility. And when they are connected to broader organizing, education, and local initiatives, they become not just symbols, but instruments of transformation.

In my own community-based work, I’ve seen how murals can also function as tools for empowerment and collaboration. When local residents, artists, and young people come together to design and paint a mural, the process becomes a form of collective storytelling. The mural is no longer just an image—it is a shared voice, a symbol of presence, resilience, and vision. Of course, murals alone won’t solve the climate crisis. But they can open the door. They can invite people in, generate awareness, spark dialogue, and create a sense of ownership and responsibility. And when they are connected to broader organizing, education, and local initiatives, they become not just symbols, but instruments of transformation.

about the writer

Erika Svendsen

Dr. Erika Svendsen is a social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station and is based in New York City. Erika studies environmental stewardship and issues related to hybrid governance, collective resilience and human well-being.

Erika Svendsen

How Murals Become Catalysts for Climate and Community Action

The paint matters—cool pigments reflecting heat, natural minerals connecting us to earth, coatings scrubbing pollution from the air.

Murals capture the moment when communities pause to envision their futures. Through observation, urban design, and collaboration, mural making becomes a catalyst for both climate and community action. The questions artists ask during this process matter: Does the imagery tell stories that need telling? Will it spark curiosity or contention, or both? What makes this place symbolic? And crucially—can the materials themselves transform the environment, with paints that cool buildings or capture pollutants from the air?

The answers to these questions reveal something deeper about communities themselves. They speak to our collective capacity not merely to represent, but to reflect and act to improve our environment. Community-created public art offers a more nuanced perspective about a place and a people—one that reveals a clear capacity for innovation, connection, and transformation.

When artists, scientists, and communities come together to design and paint murals addressing environmental themes, they engage in a form of biocultural stewardship. They steward not only the physical space but also the cultural narratives that will shape how their community interprets and responds to environmental challenges. The physical act of painting becomes environmental intervention: pigments derived from natural minerals, reflective coatings that can reduce urban heat islands, surfaces that filter particulate matter from the air. Unlike traditional policy documents, murals convey emotion, making issues accessible and personally relevant—while simultaneously making a local corner of the world more livable.

Kilia Llano’s “Conexión” project exemplifies this integrated approach. Rooting her practice deeply in the landscapes and ecosystems she inhabits—from Santo Domingo to Miami to New York—Kilia once paused her creative work to advocate for endangered flamingos, demonstrating how she sees art as inseparable from ecological stewardship. “I want murals to encourage people to be able to admire, and most of all respect these animals, and understand that nature creates a bond between humans that is unbreakable,” she explains. Her vibrant murals become acts of witness to migratory patterns connecting the Caribbean, Central America, and North America, celebrating species like the Cape May Warbler while revealing how migration connects us across borders and generations.

Mark Johnson’s work in Springfield, Massachusetts offers another powerful example. Through his art-based non-profit Chess Angels Promotions Inc., he creates collaborative spaces, such as “Bee the Change”, where art becomes a vehicle for both personal reflection and collective action. His method invites community members to see themselves in the work, transforming public art from something merely observed into something deeply felt and co-created. The physical labor of painting together—brushes in hand, conversations flowing—builds the trust and comfort necessary for meaningful dialogue about identity, history, and shared futures. These conversations are fundamental to building climate resilience.

This is the power murals hold for climate action. They remind us that addressing climate change requires reimagining our relationships with people, places, and materials. The paint matters—cool pigments reflecting heat, natural minerals connecting us to earth, coatings scrubbing pollution from the air. But so do the many hands that apply it and the neighbors who see their corner of the world transform. Beautiful work, inside and out.

Mark Johnson

In every brushstroke lies an invitation to remember our interconnectedness both to the planet and to one another.

Murals are invisible force fields that activate communities from within. They hold the power to transform space, spirit, and consciousness. While often seen as static public art, murals are in truth dynamic social instruments that generate energy, dialogue, and healing. They are symbolic meeting grounds where culture, environment, and identity converge. In this way, murals serve as catalysts not only for climate awareness but also for community cohesion and empowerment.

Murals can be understood as both cultural texts and civic rituals. They communicate layered narratives that merge artistic expression with collective memory. When a mural appears in an urban environment, it does more than beautify a wall. It disrupts invisibility. It reminds the people who walk by that they belong to a living ecosystem of history and hope. Murals invite engagement through color, symbol, and story. Each brushstroke becomes an act of resistance against alienation and a reminder that art has the capacity to shape the physical and emotional landscape of a community. The mural becomes a focal point for participation and reflection, turning observation into action.

As a community artist, I believe the work must always be done for the community and by the community. True impact happens when residents become co-creators rather than passive viewers. The process of designing and painting together builds relationships that mirror the natural balance of an ecosystem. Each person plays a role, each voice contributes a color, and each story becomes part of a collective vision. This participatory model reflects what scholars of community development describe as cultural democracy, a process through which art becomes both education and empowerment.

Involving the community in the creative process also keeps the artist and the people informed about one another. The conversations that take place during planning, painting, and unveiling reveal what residents care about most. This also gives a chance to spark much needed dialog. Listening to these voices ensures that art remains relevant and grounded in lived experience. For me, these dialogues serve as a form of research and reflection. They help me understand what is happening socially, economically, and environmentally within the community. In turn, the community gains insight into the purpose and intention behind the artwork. This exchange of knowledge builds mutual trust and creates a culturally responsive masterpiece.

In many urban environments, this process also becomes a form of therapy. The act of creating a mural allows individuals to release emotion, confront trauma, and reimagine possibility. It offers a sense of purpose and belonging that can counter the disconnection often felt in marginalized spaces. For youth in particular, mural projects can foster agency and leadership by giving them a visible role in shaping their surroundings. When the wall transforms, so does the neighborhood’s sense of identity and pride.

Murals also function as instruments of environmental consciousness. By embedding imagery of nature, sustainability, and regeneration within city spaces, artists translate global concepts of climate action into a local visual language. This can encourage people to see environmental stewardship as an immediate cultural responsibility rooted in care and awareness.

Ultimately, murals are living fields of energy that expand the boundaries of what art can do. They fuse aesthetics with activism, imagination with restoration, and personal healing with collective transformation. In every brushstroke lies an invitation to remember our interconnectedness both to the planet and to one another. Murals remind us that change begins with visibility, collaboration, and care. They teach us that the walls that divide us can also become the canvases that unite us.

Michael DeAngelo

If we prioritize excellence in the physical world over the digital experience in public art, we may inspire those to do the same in their own life.

Presently, our relationship with physical art is becoming increasingly strained as we are continually consumed by digital affectations. Murals, and more broadly public art, may be a last bastion for creations that attempt to live mostly in physical reality and not in the semiconductor realm. Trillions of dollars are being funded towards machines that are being trained to make “art”, to conjure images for those who not only have no mastery of the visual arts but also have absolutely no respect for them. Before we can ask, “How can we harness public art?”, we must first navigate what visual art is and what is the place for visual artists currently?

Visual art is an organization of visual language. Like the English language, it can be communicative, perscriptive, ornamental, salutary, poetic, or catalytic; it can be harnessed for many different means. At its base it is a way for the artist to communicate with the viewer, and the better the artist learns to master this visual language the clearer the message can be heard. The essence of this can be paraphrased from “The Practice & Science of Drawing” by Harold Speed (1913): “There is a need for both expression and technique, a work of art with no expression is a loud scream no one can understand and a work with only technique and no expression only says, look how good at technique I am.” Valuable art is born from the unique, individual, mastery of our collective visual language, the expression deriving therefrom, and all the human error found between the lines. Nothing valuable can come from generating imagery, despite the delusions many share. The value in art is that it is communicative, from one human to another, one human to many, or many humans to many. What does it mean if the author is a computer? Is it just more noise drowning out the real world for the digital? Are we forgetting the problems in our real world for those in the digital? Through mastery, visuals can be created relaying a unique, nuanced perspective of the natural world, and the audience can receive it pure. Visual artists are a lifeline to the physical world.

Public art, most times, is an experience that lives in the physical world, inherently. If the question is how can we make it catalytic, the answer is that it always is. Well-made art always is a catalyst for thought; even something as seemingly benign as ornamentation will catalyze a state of awe, slow us down, and capture us with beauty to be considered. It’s better to ask, how can we strengthen the catalytic nature of art? Leaning into physicality, leaning into public nature, leaning into the human element, accomplishes this. What does that mean? In today’s age, where we have sacrificed our real human networks to be digitized and commodified, it means growing ones that are not digital. Thousands of artists have their work unconsensually fed into machines so the unskilled can “create” digital artifacts masquerading as art. We can create projects consensually with artists in the physical world and grow a network separate from the World Wide Web. We can prioritize and support artists who strive to master our collective visual language, for its those that are the artists who will catalyze an individual, valuable perspective and communicate it succinctly to their community. If we prioritize excellence in the physical world over the digital experience in public art, we may inspire those to do the same in their own life.

about the writer

Kwadwo Adae

Kwadwo Adae is a Ghanaian-American visual & muralist based in New Haven, CT. He is the Founder & Director of Adae Fine Art Academy; an independent art school specializing in the individualized instruction of drawing and painting to children, teenagers, and adults. His practice of community collaborative public art is responsible for the installation of over thirty works of public art since 2014, including four international collaborative mural projects with children in India, Guatemala, Ecuador, and Finland.

Kwadwo Adae

The public realizes the lasting beautification effects of public art are highly desirable on both a personal and community-wide scale.

In the 11 years that I have been a muralist, I have witnessed countless ways and tested multiple theories on how mural installations have the ability to serve as catalysts for community action and climate change. The most important aspect of this to understand is that people do not inherently possess an innate understanding of how a mural installation will change any given public space until the work is fully installed. However, once a mural is successfully installed and the public has a chance to live with a completed, well executed meaningful design, the changes are often profound, and the inherent value holds the capacity to be intrinsically perceived.

One caveat in this process is that muralists must have a certain level of artistic proficiency in their public art practice in order for their work to be embraced most effectively. Due to the fact that mural installations may largely be a consentless process, a well-received mural should be impressive to a certain degree. If the artwork showcases sub-amateur level skills, the community response may be overwhelmingly negative. In order for mural installations to be used as effective catalysts for climate change, the message needs to be proficiently executed.

A common response to mural installations fully embraced by the community is something I call “The Contagious Encore Effect” where the shared public experience of the beautifying effects of a new mural installation suddenly allows people to see subsequent blank wall spaces as potential opportunities for additional public art. The public realizes the lasting beautification effects of public art are highly desirable on both a personal and community-wide scale. Using the highest quality materials, the life of a mural is approximately ten years. Extending beautification efforts with the longevity of trees is what started beautiful partnership between Urban Resources Initiative and myself to have street trees planted as an important part of subsequent mural installations. Whenever possible, I utilize street trees from URI to create murals that fight climate change. For example, I created Sparrow Squadron in 2020 in response to an egregious act of police violence that occurred when Yale & Hamden Police officers fired 16 shots into the car of an unarmed black couple in 2019. I requested Urban Resources Initiative plant two serviceberry and a hackberry tree as part of the public art installation as a means to restore peace and freedom that police violence steals from a community.

In 2023, in The Hill neighborhood, a few months after completing the installation of Everyone Deserves To Come Home To Flowers, I requested that URI plant an Eastern Redbud tree across the street whose flower buds are the same color as the orchid blooms in the installation. Months later I witnessed a new mural installation on the convenience store across the street featuring Gorilla Lemonade on the Sylvan Ave corner of the street. In the last ten years New Haven has blossomed with muralists. Seeing that the installation of well executed murals is contagious, I am hopeful that other New Haven muralists will begin to incorporate tree plantings in their mural installation designs. Our urban forests need augmenting, especially in all of the formerly redlined neighborhoods of New Haven, Newhallville, Dixwell, Fair Haven, West River, and The Hill.