about the writer

Marufa Sultana

Marufa Sultana is an urban ecologist with expertise in wildlife biology, biodiversity conservation, and nature-based solutions, and has experience in both academic and non-academic sectors. She is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Technology Assessment and Systems Analysis (ITAS) at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, where her research focuses on exploring solutions for co-designing future sustainable cities for both people and wildlife. Marufa earned her doctorate in natural sciences from the University of Freiburg, Germany. Prior to her current role, she worked on nature-based solution projects at ICLEI Europe and contributed to biodiversity and ecosystem conservation initiatives at IUCN in Bangladesh.

Introduction

It is as if wildlife remains something to be “managed”, something that only fits within discussions of urban ecosystem services or disservices, rather than being recognized as a vital stakeholder in shaping our shared environments in cities.

Cities are primarily built for humans, not for wildlife. But as we continue to expand and reshape urban areas, the likelihood of encountering and interacting with wildlife has increased. Numerous examples of such interactions have been documented from many cities across Europe and North America, which have experienced a historical urbanization process. For many years, these interactions were largely viewed through the lens of management by wildlife biologists and urban professionals.

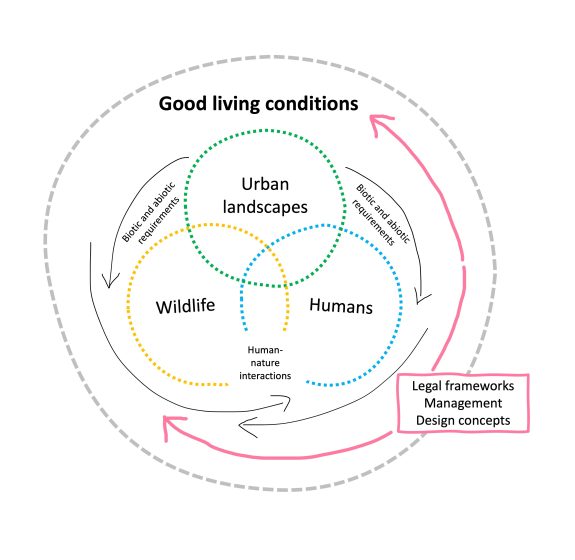

Recently, we have noticed a shift from traditional utilitarian thinking that focused on wildlife management mainly in terms of human usefulness, toward a more holistic view. Scientists and practitioners are starting to collaborate in building sustainable urban futures for both humans and non-human species, aiming for coexistence and shared benefits that allow us to live in harmony with nature (IPBES, 2024). Emerging concepts like “wildlife inclusive city” (Apfelbeck et al., 2020; Kay et al., 2022), “multispecies justice” (Raymond et al., 2025), and “animal-aided design (Weisser & Hauck, 2025), are propelling debates about moving beyond an anthropocentric worldview and giving wildlife an actual place at the discussion table in urban planning.

This challenges us to view wildlife not just as something to manage, but as active stakeholders in our decisions about future urban transformations. Giving wildlife a voice in how we plan and design urban spaces can help create cities that are healthier, more beautiful, and more balanced for everyone. By inviting wildlife into the conversation―not just symbolically, but through data, design, and policy―we can help build cities that are resilient and just.

But what does it take to give wildlife a place as stakeholders in decisions about urban planning? Because even though we speak about giving wildlife a voice, there’s still a lot of tension and resistance from multiple directions in society. It is as if wildlife remains something to be “managed”, something that only fits within discussions of urban ecosystem services or disservices, rather than being recognized as a vital stakeholder in shaping our shared environments in cities. Will we manage to overcome century-old and entrenched dichotomies, and what could be concrete pathways forward?

References:

Apfelbeck, B., Snep, R. P. H., Hauck, T. E., Ferguson, J., Holy, M., Jakoby, C., Scott MacIvor, J., Schär, L., Taylor, M., & Weisser, W. W. (2020). Designing wildlife-inclusive cities that support human-animal co-existence. Landscape and Urban Planning, 200, 103817. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LANDURBPLAN.2020.103817

IPBES (2024). Summary for Policymakers of the Thematic Assessment Report on the Underlying Causes of Biodiversity Loss and the Determinants of Transformative Change and Options for Achieving the 2050 Vision for Biodiversity of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. O’Brien, K., Garibaldi, L., Agrawal, A., Bennett, E., Biggs, R., Calderón Contreras, R., Carr, E., Frantzeskaki, N., Gosnell, H., Gurung, J., Lambertucci, S., Leventon, J., Liao, C., Reyes García, V., Shannon, L., Villasante, S., Wickson, F., Zinngrebe, Y., and Perianin, L. (eds.). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11382230

Kay, C. A. M., Rohnke, A. T., Sander, H. A., Stankowich, T., Fidino, M., Murray, M. H., Lewis, J. S., Taves, I., Lehrer, E. W., Zellmer, A. J., Schell, C. J., & Magle, S. B. (2022). Barriers to building wildlife-inclusive cities: Insights from the deliberations of urban ecologists, urban planners and landscape designers. People and Nature, 4(1), 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/PAN3.10283/SUPPINFO

Raymond, C. M., Rautio, P., Fagerholm, N., Aaltonen, V. A., Andersson, E., Celermajer, D., Christie, M., Hällfors, M., Saari, M. H., Mishra, H. S., Lechner, A. M., Pineda-Pinto, M., & Schlosberg, D. (2025). Applying multispecies justice in nature-based solutions and urban sustainability planning: Tensions and prospects. Npj Urban Sustainability, 5(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00191-2

Weisser, W. W., & Hauck, T. E. (2025). Animal-Aided Design–planning for biodiversity in the built environment by embedding a species’ life-cycle into landscape architectural and urban design processes. Landscape Research, 50(1), 146–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2024.2383482

about the writer

Manisha Bhardwaj

Dr Manisha Bhardwaj is a wildlife ecologist, motivated to identifying and mitigating the negative impacts of the human activity on wildlife. At University of Freiburg, she leads the research theme of “Human-Wildlife Interactions”, in the Chair of Wildlife Ecology and Management. Her research explores how human activity, particularly transport infrastructure and other land-use changes, influences behaviour and ecology of wildlife.

about the writer

Tanja Straka

Tanja is a guest professor in Urban Ecology at the Freie Universität Berlin, with a PhD from the University of Melbourne. She is passionate about understanding how people and wildlife can thrive together in cities. Bridging ecology and social science, her work explores human-wildlife relationships, the drivers of human behaviour, and the impacts of anthropogenic stressors on urban biodiversity, with a special love for bats. Tanja collaborates closely with NGOs and her career has taken her across Europe, West Africa, India, New Zealand, and Australia.

Manisha Bhardwaj & Tanja Straka

Giving wildlife a place as stakeholders in urban planning is not about perfection. It is about curiosity and the willingness to understand what it means to share space in the city.

Concepts such as wildlife-inclusive cities, multispecies justice, or approaches like Animal Aided Design offer valuable tools and frameworks to integrate ecological and social needs of cities. Giving wildlife a voice does not mean pretending animals participate in meetings. It rather means representing their needs through our, albeit sometimes limited, current ecological knowledge while simultaneously working with people’s values, emotions, and encouraging reflection on our own behaviour with wildlife. Urban planning cannot outsource responsibility to design alone. In order to have successful wildlife-inclusive cities, a transformative rethinking of human-nature relationships in built environments is needed. And moreover, they will only succeed if people can live with the outcomes.

Human-wildlife conflicts are often rather human-human conflicts. Someone will feed wild boar in parks because they find them entertaining and fascinating, while their neighbour will chase them away violently for becoming comfortable around humans or destroying property. The truth is, while wild boar are at the center of this particular conflict, feeding and desensitizing wild boar to humans is the mechanism by which the conflict occurs. What is often missing from discussions about coexistence with urban wildlife is honest reflection on how our own behaviour creates the very situations we later frame as “wildlife problems”. Giving wildlife a place at the table does not only mean designing urban areas for wildlife, but also means holding humans accountable for the conditions we produce through our behaviour.

Preferences play a large role in acceptance and tolerance. Wildlife lives with us in cities, whether we like some species or taxa or not. In cities, birds or pollinators are often celebrated and actively designed for, as in projects such as “Mehr Bienen für Berlin ― Berlin blüht auf” or the increasing number of studies related to birds and well-being1. In contrast, mammals and reptiles are more often discussed and studied in the context of conflict, risk, or nuisance2. Research from Germany, for example, shows clearly that while squirrels, hedgehogs, and foxes are generally appreciated, wild boars, raccoons, and rats are far less welcome3. If wildlife-inclusive cities only include the species we already like, we are not really moving beyond an anthropocentric worldview. So, the question is: do we really need to like wildlife or benefit from them in order to share the urban environment, or can we approach this differently? In other words, how to give the less-liked or “less-beneficial” wildlife a “stake” in this discussion.

Knowledge about species and their behaviour in urban areas is important, but it is not sufficient for them to be accepted in cities. We tend to overestimate how much information alone can change attitudes and people’s behaviour. People may know that a species is harmless or ecologically important and still feel fear or rejection toward it. Emotional connection plays a critical role here. Feeling connected to wildlife and nature in general is not built through constant exposure, but through positive encounters, as a recent study from the UK shows4. A single meaningful experience with urban wildlife, such as an urban fox, can shape our relationship with wildlife more strongly than repeated neutral or negative ones. The challenge for urban planning, therefore, is not simply to increase biodiversity but to create conditions for positive, low-conflict encounters between people and wildlife.

We also need humility. We still do not really know how to live with some wildlife in dense urban environments, and that is okay. What is needed is openness to experiment, to accept failure, and to learn. Dichotomies between nature and city, wild and human, useful and problematic will not disappear overnight. But by acknowledging complexity, reflecting on our own behaviour, and focusing on meaningful human-wildlife relationships rather than control and conflict alone, we can begin to move forward.

Giving wildlife a place as stakeholders in urban planning is not about perfection. It is about curiosity and the willingness to understand what it means to share space in the city.

References

1 Methorst, J. (2024). Positive relationship between bird diversity and human mental health: an analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. The Lancet Planetary Health, 8(5), e285-e296.

2 Methorst, J., Bonn, A., Marselle, M., Böhning-Gaese, K., & Rehdanz, K. (2021). Species richness is positively related to mental health–a study for Germany. Landscape and Urban Planning, 211, 104084.

3 Moesch, S. S., T. M. Straka, J. M. Jeschke, D. Haase, and S. Kramer-Schadt. 2024. The good, the bad, and the unseen: wild mammal encounters influence wildlife preferences of residents across socio-demographic gradients. Ecology and Society 29(3):6.

4 Morton, F. B., & Soulsbury, C. D. (2025). Experiencing the wild: red fox encounters are related to stronger nature connectedness, not anxiety, in people. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 1-18.

about the writer

Joëlle Salomon Cavin

Joëlle Salomon Cavin is a geographer and professor at the Institute of Geography and Sustainability at the University of Lausanne. Her research and teaching focus on environmental geography and on relationships between cities and nature(s). In 2025, she founded the SBU (Sales Bestioles Urbaines) research group, which aims to better understand how unloved animals – such as rats, pigeons, bedbugs, fish parasites, and others – inhabit cities, and to study the full range of relationships that develop between these animals and human within the urban environment.

Joëlle Salomon Cavin & Lazare Duval

Bed Bugs and the Cinémathèque française: Giving Less Space to Unwanted Wildlife in Urban Planning?

Managing unwanted animals does not mean treating them as passive objects.

The observation that wildlife[11] is insufficiently integrated into urban planning is valid, and it could also be extended to architectural design more broadly. However, I would like to question the idea that the solution necessarily lies in giving more space to these animals as stakeholders, which seems to be the implicit direction of this roundtable. In some cases, the issue may instead be about giving them less space through urban planning.

Our work focuses on so-called unloved animals (Salomon Cavin, 2022) such as bedbugs, rats, pigeons, cockroaches, or tiger mosquitoes—which are commonly associated with disturbing or even hostile forms of animality and are widely considered undesirable in urban environments. Urban dwellers often resist cohabiting with these species, especially within the intimacy of their homes, as they can significantly and sometimes dramatically deteriorate the quality of life. This raises an important point: urban planning cannot entirely move away from an anthropocentric perspective, as it is ultimately meant to serve human well-being, which may be seriously compromised by certain unwanted species.

Unwanted animals, therefore, offer a productive entry point into questions of coexistence between humans and non-humans. Yet discussions on multispecies urbanism have largely focused on ethical questions of desired multispecies companionship, emphasizing encounters, convivialities, and requirements of care for nonhuman species —while often overlooking the very real difficulties of living with what Franklin Ginn and colleagues (Ginn et al., 2014) call “awkward creatures.

While the increased recognition of biodiversity as a stakeholder in urban planning decision-making is essential from the perspective of multispecies justice, it is important to acknowledge that certain species, given their specific ecologies, behavioral patterns, and rates of proliferation, need to be managed rather than welcomed.

A concrete example is the recent temporary closure of the Cinémathèque française in Paris due to a bedbug infestation. Following a screening of Alien—an anecdote I cannot resist mentioning—several spectators reported bringing bedbugs home, confirmed by painful bites. The closure of the four screening rooms for over a month was necessary to treat the seats and carpets through heat.

This case illustrates how coexistence with certain forms of wildlife can become not only uncomfortable but also disruptive to urban life. At the same time, such cases highlight that these species are far from passive. Bedbugs, like other unwanted animals, are highly adapted to urban environments that were not designed for them. They take advantage of housing, public transport, and public facilities to spread, feed, and reproduce, directly shaping urban functioning—for example, by forcing the temporary closure of infrastructures, such as cinemas, but also shelters for unhoused people. In this sense, they challenge the idea that animals are merely acted upon by human planning, and instead appear as active agents within urban socio-ecological systems (Urbanik, 2012).

Similar dynamics can be observed with tiger mosquitoes, vectors of serious diseases, or with German cockroaches, which thrive in urban buildings and “actively” resist human control (Biehler, 2009). These examples remind us that not all human–animal relationships are harmonious, and that coexistence often involves conflict, avoidance, and unequal power relations.

I would argue that unwanted animals, unlike much of biodiversity, often benefit from the way we design urban spaces for ourselves. Just as sewer systems created ideal habitats for brown rats (Vergopoulos, 2021), modern apartments offer stable temperatures and abundant resources for bedbugs (Borel, 2016) and cockroaches (Reinhardt, 2018). These species must therefore be taken seriously as actors in urban planning. However, the key question is not how to welcome them, but rather how to design urban environments in ways that limit their proliferation.

Managing unwanted animals does not mean treating them as passive objects. On the contrary, fully acknowledging their capacity to adapt to urban environments—and the challenges they may pose—highlights their role as stakeholders in urban planning.

As a last word…from this perspective, pest-control professionals may also be crucial—yet often overlooked—stakeholders to include in discussions on sustainable urban futures.

References:

Biehler, D. D. (2009). Permeable homes : A historical political ecology of insects and pesticides in US public housing. Geoforum, 40(6), 1014‑1023. https://doi.org/10/ffd5g2

Borel, B. (2016). Infested : How the Bed Bug Infiltrated Our Bedrooms and Took Over the World (Reprint edition). University of Chicago Press.

Ginn, F., Beisel, U., & Barua, M. (2014). Flourishing with Awkward Creatures : Togetherness, Vulnerability, Killing. Environmental Humanities, 4(1), 113‑123. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3614953

Reinhardt, K. (2018). Bedbug. Reaktion Books.

Salomon Cavin, J. (2022). Indésirables! ? Les animaux mal-aimés de la ville. EPFL Press.

Vergopoulos, H. (2021). Les rats de Paris : Une brève histoire de l’infamie. Le murmure.

[11] In this contribution, I use the term wildlife to refer to animals whose presence has not been intended or desired by humans.

about the writer

Gitty Korsuize

Gitty Korsuize works as an independent urban ecologist. She lives in the city of Utrecht. Gitty connects people with nature, nature with people and people with an interest in nature with each other.

Gitty Korsuize

The Voice of Nature Needs Human Mouths ― Please Speak Up!

All these stories need human mouths ― so please, use your own (professional) voice and speak up for nature!

As an urban ecologist, I am supposed to be the “voice of nature” in my city. In an urban project, I am just one of the many voices that need attention. Looking back on the projects I’ve worked for, the most successful ones for nature where the ones in which the need for green or nature was voiced by multiple stakeholders: the project manager who had a great fondness for birds, the citizens living next to the project who wanted to add more nature to their park, the colleague from the water department who needed a green area for water storage or the politician keen on improving projects for animals. Multiple voices for nature added to the amount of nature realized.

In the past 20 years, I have seen the awareness of nature rise in the Netherlands. Voices for nature came from new stakeholders. Some important Dutch milestones:

- Incorporation of the Birds and Habitat Directive in Dutch legislation strengthened the legal voice. The law helped to give nature a legal backbone to prevent further deterioration. After some years of figuring out the implementation, nature was a stakeholder that needed to be heard.

- Declaration of the house sparrow as an endangered species strengthened the voice of “common people”. Even for people who normally do not identify themselves as naturalist, this was a wake up call. People realized that even common species were declining and were becoming endangered. Nature could not be taken for granted anymore.

- Rapid decline of insects strengthened the scientific voice. The most impactful was the realization that many people had with the windscreen of cars. Many remembered that in the seventies, these were full of insects. You had to clean them almost weekly. Nowadays, they are almost clean.

All stories that strengthen the voice of nature as a stakeholder in projects. If we want to give nature a stronger position, we need more voices and more stories. We need these stories to win the hearts of other stakeholders. This will give nature not one voice, but multiple voices in a project.

How do we get more people to speak in favor of nature? The protection of nature is instilled in your childhood. Nature education in schools is the obvious way. Green areas near housing areas for children to roam freely and to discover nature are even better. This is a challenge when our cities become less and less green, and the pressure on green areas with multiple functions becomes greater.

Other ways to share stories about urban nature are through art or social media. In the early days of Twitter, the “Utrecht urban ecology” account told short stories on local species. It was also followed by local politicians and helped them voice the need for nature in local projects in the decision-making process. Nowadays, the Utrecht Fishdoorbell attracts millions of views and, in that way, is a voice for the fish in our waterways.

One of my favorite ways to share more stories on urban nature is by involving volunteers in the monitoring of green areas and urban species. In this way, volunteers become aware of the effect projects have on urban nature. Their observations become part of the story, and they also become spokesmen for urban nature.

Multiple voices for nature strengthen the weight of nature in the project. Once nature is established as a stakeholder in the project, it becomes easier to incorporate nature into the design. The next discussion is which nature do we want, and how do we achieve this. For this, inspiration can be found in other projects, guidelines, policies, and the stories we tell about them. For example, my article on guidelines for nature.

All these stories need human mouths ― so please, use your own (professional) voice and speak up for nature!

about the writer

Johan Enqvist

Dr. Johan Enqvist is a sustainability scientist at Stockholm Resilience Centre, studying how people in cities deal with nature that is not behaving the way they want it to. He leads the Unruly Natures project (www.UnrulyNatures.com), which focuses on urban conservation conflicts: situations where people struggle to agree on what kind of wildlife should be allowed in cities. Johan’s academic journey has explored urban environmental stewardship as an expression of human-nature connectedness in settings where the two often seem cut off from one another. He uses mixed and often participatory methods to engage with communities’ lived experiences, surface their stories, and stimulate empathy and imagination.

about the writer

Kinga Psiuk

Kinga Psiuk is a PhD Candidate at the Centre for Sustainability Transitions, Stellenbosch University. With a background in social psychology and social-ecological resilience, her research focuses on human-nature relations. Since 2021, she has been studying subjective perceptions of residents in baboon-visited areas of Cape Town.

Johan Enqvist & Kinga Psiuk

Unruly neighbours: Good manners when urban wildlife have a seat at the planning table

If we ignore what unruly urban wildlife is telling us about the planning of our cities, will we also treat other species as “unnatural” when they evolve new behaviour or physiology to survive in the world we are shaping?

The short answer to this roundtable’s prompt is: we have already given wildlife a place as stakeholders in urban planning decisions. Or rather, wildlife took it. As the rich contributions on this page illustrate, adaptable species have learned to exploit the novel niches that cities offer: food-rich waste streams, predator‑free landscapes, and infrastructure that doubles as convenient roosts and dens. While this can affect the city’s physical form to some degree, the greatest impact from wildlife on urban planning is that it challenges common assumptions about people’s relationship to the rest of nature.

Environmental stewardship and conservation initiatives usually assume that nature is either pristine and needs protection, degraded and needs restoration, or used by humans and needs sustainable management. However, wildlife that thrives in cities, from otters in Singapore and wild boars in Rome to coyotes in Los Angeles and baboons in Cape Town, are neither of these things. They represent what we call an unruly form of nature, one that has the agency and ingenuity to fill new niches in human-dominated spaces, in defiance of human intentions and in spaces we consider ours. This creates a dilemma for stewardship: should people in cities reject, try to control, or adapt alongside these new neighbours? The divisiveness of such questions surfaces deeper conflicts about who belongs in a city, what counts as acceptable behaviour, and what constitutes a healthy relationship between humans and wild animals.

Cape Town’s baboons are a vivid case. Highly intelligent, social, omnivorous, and agile, they easily slip between vineyards, nature reserves, and kitchens and can cause damage to property and scare residents. Every day, paintball-armed rangers work to deter baboon troops from urban areas. On occasion, individual baboons deemed too hard to control are euthanised, but many residents and animal rights groups oppose this, arguing that baboons were “here first” and humans should learn to adapt to them. Others demand more effective deterrence and control of baboons. The public debate is often highly polarised with strong emotions on both sides, and public meetings and decision-making have repeatedly stalled in search of permanent solutions to what is fundamentally a dynamic, ever-evolving situation.

Having studied people living alongside baboons since 2021 (read more on our website), we believe Cape Town has some important lessons to offer.

Firstly, planning with urban wildlife differs from conventional conservation since there is no baseline of “natural” behavior―cities aren’t natural. Wildlife that enters them can cause both overly fearful and overly romanticised misconceptions, but allowing for a range of perspectives is important for maintaining the collective imagination of what living alongside unruly natures could look like.

Secondly, dealing with the unruly means dealing with disagreement, not just wildlife encounters. This requires empathy to recognise the legitimacy of different values, risk perceptions, and claims to urban space, while seeking creative ways to bring people together, correct misconceptions, and identify common ground where it exists.

Thirdly, and perhaps most fundamentally, living with the unruly means being in a form of relationship: an unfolding interplay between human culture and animal adaptation, rather than caring for a piece of territory. But as in any relationship, it is important to know where to set boundaries. Care with no boundaries can lead to habituation and co-dependence, while restricting care too much can invite cruelty and vigilantism. Neither are signs of a good relationship.

Cities are some of the most human-altered environments that exist, but anthropogenic impact reaches ecosystems far beyond urban areas. If we ignore what unruly urban wildlife is telling us about the planning of our cities, will we also treat other species as “unnatural” when they evolve new behaviour or physiology to survive in the world we are shaping? The presence of wildlife in cities provides an opportunity to move away from abstract nature ideals to practical co‑adaptation, to recognise this presence early enough and design with it―compassionately, revisiting and renegotiating the terms of our unfolding relationship with wildlife.

about the writer

Kelly Baldwin Heid

Kelly Baldwin Heid holds an MSc in Global Urban Health from the University of Freiburg, where she is currently completing a PhD exploring the connections between urban biodiversity and human health. As an Expert on the Biodiversity and Nature-based Solutions team at ICLEI Europe, Kelly works with cities to develop Urban Nature Plans, bridge the biodiversity-finance gap, and facilitate capacity building programmes.

Kelly Baldwin Heid

We may never know what a fox wants from a city.

I am a strong advocate for valuing nature and wildlife in their own right—not simply as tools for human wellbeing. Yet I’m not convinced we can literally place wildlife “at the table” in urban decision-making. We already struggle to meaningfully include diverse human communities, with those most affected often the least able to shape decisions. If we cannot guarantee humans an equal say, how could we ever fairly represent more-than-human species whose voices we cannot hear?

Like people, wildlife is not a unified stakeholder. It encompasses thousands of species, each with distinct ecological roles, lifestyles, and pressures. Some seem to thrive in cities, but we don’t know whether they prefer asphalt or are forced there by shrinking habitat. Species live where they can; survival does not signal preference.

Rewilding offers a humbling lesson. When humans step back and allow natural processes to unfold, life rebounds in astonishing ways. Yet, rewilding also exposes the limits of our imagination: we cannot ask a fox whether it prefers trash bins or woodland, nor whether an urban bee longs for meadows it may never see. Species are evolving in real time under urbanisation, but we may never know whether this reflects adaptation or desperation.

Since Christopher Stone’s 1972 essay Should Trees Have Standing?, lawmakers have tested what it might mean to give nature a place in governance. A landmark moment came in Aotearoa, New Zealand, in 2014, where a Treaty settlement recognised the Whanganui River as a legal person. Ecuador embedded the rights of nature in its constitution; courts in Colombia, Bangladesh, and India have granted legal standing to rivers, with India going further still to extend personhood to the entire animal kingdom. Pakistan affirmed an elephant’s right to a healthy environment, Bolivia and Panama recognise Mother Earth’s inherent rights, and recent decisions in Spain and Germany open pathways within the EU. In the United States, community-led initiatives have adopted rights-of-nature ordinances. In 2019, Toledo, Ohio, passed a Lake Erie Bill of Rights empowering residents to sue on behalf of the lake. The legislation was later struck down, however, revealing just how firmly human systems still police the boundaries of “who counts.”

These developments are inspiring, but they remain largely symbolic without translation into action. And crucially, humans still speak for nature. As legal scholar Gwendolyn Gordon reminds us, legal personhood does not flip a switch that makes something fully a person. Recognising personhood simply begins a conversation about which rights apply, who asserts them, and how far they reach. Scientists, Indigenous stewards, community associations, planners, and legal guardians—each would interpret “what nature wants” differently. The risk of projection is impossible to eliminate.

Which is why the most meaningful shifts may not come through courts, but through local, neighbourhood-scale practice.

Part of the solution lies in shifting towards nature-first planning: reframing cities as shared habitats, not human-only enclosures. Soil first, water first, habitat first. Pocket meadows instead of mown medians. Gardens beneath street trees. Scrub and deadwood are recognised as ecological infrastructure.

Equally important is nurturing nature connection. People protect what they care about—and caring grows from exposure and ordinary contact with nature: noticing street trees on the way to school, listening to the birds while you take out the trash, brushing against wildflowers in a sidewalk garden. Urban greening seeds these interactions everywhere. Research shows nature connection reliably predicts wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviour—and nearby, everyday nature further strengthens that link. Change happens block by block.

I work on a few EU Horizon projects that put these ideas into practice. In Urban Nature Plans+ and Commit2Green, we are working with European cities to embed nature and greening into governance—not as an afterthought, but as a unifying and organising principle. We work across municipal departments to help cities shift from managing nature at the margins to planning with nature at the core.

We may never know what a fox wants from a city. But we can create places where more species can survive and flourish—not because they serve us, but because they belong. And in doing so, we can rediscover cities that are healthier, more interesting, and resilient, and infinitely more alive.

about the writer

Leonie Fischer

Leonie’s scientific focus is especially on the ecology of human-influenced habitats in both tropical and moderate regions, including urban ecology and urban restoration. She also works on a deeper understanding how people value urban nature, and what influences their attitudes. Basic part of her research work is its practical orientation and application.

Leonie Fischer

From Target Species to Planners of Urban Landscapes?

On a green wall that includes a bedroom window, it may be the positively perceived butterfly that delights many people, and the spider that some humans would rather not prioritize in their immediate surroundings.

The inclusion of wild species has a long tradition in landscape planning in Germany. This arose, among other things, from nature conservation movements, acute environmental problems, and the need to develop solutions for them. Yet, only later were these approaches transferred to cities, and concepts were developed to preserve and promote wild species within landscape planning that addressed urban landscapes in particular. Here, species were and still are often understood as indicators that reflect, for example, the quality of an area and its natural components, or whose future presence is defined as a target for management measures. The basis for such inclusion is often provided by (local) legal frameworks that protect the existence of species and species communities, and stipulate that natural resources must be maintained, developed, and, where necessary, restored. Traditionally, these legal frameworks have primarily addressed the deterioration of populations and the state of their living conditions. At the same time, such legal requirements can also serve as a basis for further promoting species and their habitats in urban areas, as the Federal Nature Conservation Act expressly mentions populated areas (“besiedelt” in German, in addition to unpopulated areas) as some sort of spatial reference point for the conservation of nature and landscape.

Nevertheless, and especially in highly densifying cities, there is once again potential for greater inclusion of wildlife and their specific perspectives in the planning and design of urban landscapes. Even though a great deal is known about individual species and there may be a growing interest in integrating wildlife into urban areas, the ways in which planners, experts from nature conservation, and urban ecologists come together are not entirely defined or structured. This may also come with the different professional backgrounds, which are not necessarily combined for the issues of landscape planning, and underlying working modes. In some cases, official planning processes may be difficult to change for more intense feedback loops between stakeholders. However, in light of the multiple crises that need to be tackled for good living conditions, this brings us back to the potential of wild organisms as umbrella species or target species, a concept that has long been part of landscape planning in Germany―an approach that we see exactly in newer approaches: individual species are used as example species and their specific life cycles through the seasons help develop adapted designs for green spaces. Of course, the selection of species plays a major role here, and so do the spatial context and the quality of resources in relation to the species, defining their requirements as well as the potential of a site per se.

For such a holistic approach to landscape design, studies dealing with human perceptions of natural components may be helpful. They identify that there are species that humans prefer or dislike, often bound to values and cultural norms or traditions. Thus, they bring together which wildlife may exist in an urban context, how people would deal with them, or what measures could be taken to create a common space for all. On a green wall that includes a bedroom window, it may be the positively perceived butterfly that delights many people, and the spider that some humans would rather not prioritize in their immediate surroundings. Although such considerations do involve anthropocentric assessments of wildlife―leaning on the understanding of nature’s benefits for people―they can be helpful for planning processes to explore spaces for mutual acceptance. If such considerations are shared among different disciplines, everyone can benefit, and wildlife will increasingly join to plan better urban landscapes.

about the writer

Minwoo Chun

Minwoo is a climate & biodiversity programme officer at ICLEI Korea Office. Having backgrounds in meteorology and anthropology, he pursued Master’s degree in climate change policies to infuse his multidisciplinary backgrounds into holistic climate studies. As a biodiversity officer, Minwoo is keen to add more-than-human approaches to his worlding of the Anthropocene, believing that the future urban will flourish in diversity of all aspects. Flat white addict and a cat person. Knits sweaters for meditation purpose when things don’t turn out well.

Minwoo Chun

In nature (and in cities), no one survives alone.

A few months ago, I noticed a weird hog statue in front of the restaurant in my hometown, Sejong City. This Korean BBQ place was “visited” by a fellow wild boar, which resulted in shattering a few glass walls. I don’t know what happened to the boar afterwards, but it seems like the restaurant wanted this visitor to become their mascot, referring to the statue they placed in front of their shop.

Besides this iconic advocacy of the wild boar, Sejong is actually a city that features unique urban biodiversity, along with the history that the area once was an agricultural region of rich rice paddy landscapes. Sejong has now become one of the recently developed administrative cities in South Korea, with most of the national government offices residing there. This, in turn, posed risks of environmental destruction of the region, which includes multiple threats to vulnerable and endangered species such as water deer and gold-spotted frogs. Even at this moment, civil society and environmental NGOs are protesting at the Geum River banks for over 600 days to deconstruct artificial dams that are obstructing the river flow in Sejong City.

Bringing multispecies thinking into the real city

Sejong wouldn’t be the only city that is facing the struggle of the coexistence of humans and non-humans. From the multifaceted interfaces of human and non-human encounter, we should raise questions of whether human-centred cities would be sustainable in the triple-crisis world we are living in. And also—as a practitioner myself, I believe we should also need to cultivate feasible answers and try implementing innovative actions, along with and based on rich discourse of more-than-human approaches [1].

In Korea, we see proliferating discussions on more-than-human approaches throughout academia and civil society during the past decade [2]. This is not only confined to the “charismatic” species that are mostly paid attention to (such as cats and dogs), but also expanding to the realms of plants, trees, and even ecosystems themselves. One of the recent creative approaches in Korea is the “City Tree Club”, an initiative led by Seoul KFEM (an environmental NGO in Korea). The initiative provides an online social platform based on the real-world practice that connects street trees and citizens with the notion of care and companionship.

Towards the feasible multispecies policies (and world)

While these movements and thoughts are increasingly introduced and developed in Korea, attempts to institutionalise multispecies thought into policies or political frameworks seem not yet mainstreamed. As a biodiversity officer working with local governments in Korea, I feel that we need more time to make more-than-human approaches feasible in the policy process, since many of the biodiversity policies are still heavily capitalistic and human-centred.

However, I also see some silver lining that there are local government officials who struggle to bring ecological perceptions into the local policy, with the limited resources they have. From protected areas management to payment for ecosystem services, carefully implemented policies entail stakeholders’ thoughts on how to cultivate harmony with nature and ecosystems embedded in our surroundings of urban environments. While these policies still objectify non-human beings as “life that should be protected” or “organisms that should be isolated in the protected area”, we should aim to incorporate them as a crucial actor in the policy process, as they already are in the real world.

As the “City Tree Club” highlights the companionship of people and trees, we need to acknowledge non-human beings as fellow “denizens” that interact with other human and non-human beings [3]. This awareness will lead to the collective understanding that the coexistence and inclusion of wildlife is inevitable, and in turn, to demand a holistic institutional framework to make coexistence sustainable.

And in the heart, I hope people centre the value of care, creating resilience in this world of diversity. Because in nature (and in cities), no one survives alone.

[1] Lorimer, J., & Hodgetts, T. (2024). More-than-Human (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315164304

[2] Choi, MA. (2025). After multispecies ‘entanglements’: A critical review of more-than-human social sciences. Space and Environment, 35(3), 246 – 290.

[3] Srinivasan, K. (2019). Remaking more‐than‐human society: Thought experiments on street dogs as “nature”. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 44(2), 376-391.

about the writer

Madhusudan Katti

Madhusudan is the Director of Science, Technology, and Society, and Associate Professor of Public Science in the Department of Integrative Humanities and Social Sciences at North Carolina State University.

Madhusudan Katti

On the Rights of Swallows to Nest in Buildings

Humans always share our cities with other beings, often attracting them to urban living by disrupting their habitats and food supplies.

When I worked at Fresno State University, teaching the biology of reptiles and birds, I had an ongoing beef with campus operations overseeing building and grounds maintenance. Our Science building had some nice overhanging alcoves that migratory Cliff Swallows found ideal to build nests in every spring. I loved that my students could observe them during the few weeks of the swallows’ fleeting summer in Fresno. To campus operations, however, the birds were a nuisance, making a daily mess of droppings for workers to clean up. Their solution was to use nylon nets to block the birds’ access to their preferred alcoves—even though that also took work and marred the building’s aesthetics. I kept reminding them that these swallows were legally protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which prohibits disrupting their reproduction by disturbing their nests or nesting behavior. They would counter that the nets were put up outside the breeding season, so no active nests were being disturbed, and the birds could simply go somewhere else, never mind the challenges they face in finding suitable habitat amid the concrete jungle of the city. While we argued, some of the birds kept finding ways to evade the nets and nest in some alcove anyway. And on they went with their spring dances while humans struggled to come to a simple compromise: pay more workers for cleaning duties during the 6-8 weeks of the year when the birds visited us! Why can’t we treat them as the beautiful guests they are, I wondered?

Whether we like it or not, humans always share our cities with other beings, often attracting them to urban living by disrupting their habitats and food supplies. Yet, the notion that non-human beings may have just as much of a right to live and thrive in spaces we consider our own seems anathema to the Western mind, even though it is integral to the value systems of many Indigenous cultures around the world. Prominent thinkers of the so-called European Enlightenment who shaped modern scientific philosophy categorically separated humans from other beings, placing ourselves on a higher pedestal with dominion over the planet. Through the colonial and intellectual expansion of Europe, these ideas spread throughout the world and became the basis of most modern legal systems, which grant humans certain inalienable rights while denying them to other species. Nowadays, conservationists evoke a similar hierarchy of beings to remind us that our dominion over nature comes with the responsibility of being good stewards who take care of all life on earth.

It is only recently that this hierarchy itself has been challenged by growing movements for the Rights of Nature, which advocate for granting legal rights to non-human beings such as trees and animals, and even non-living entities such as rivers. Drawing on legal theories developed since Christopher Stone asked “Should Trees Have Standing” in a landmark 1972 paper, and on wisdom from non-western ontologies and epistemologies, the movement is gaining ground (and scientific support) worldwide, and has successfully pushed for laws recognizing species or even local ecosystems as entities with legal standing in jurisdictions ranging from local municipalities to even national constitutions, such as that of Ecuador.

The Rights of Nature movement gives me hope that we can all learn to reconcile differences between human and non-human beings and recognize that we all share the same right to life, liberty, and justice. And so, I imagine a world where the Cliff Swallows are free to nest in the nooks of every building and continue to brighten the spring for their human tenants who welcome them as cherished guests every spring.

about the writer

Navya Raju

Navya Raju is an Ecologist at Perkins&Will, working firmwide to integrate ecology as a core design driver across architecture, landscape architecture, and urban design teams. A graduate of the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), her work is grounded in systems thinking and an ecological worldview centered on people, place, and planetary health.

about the writer

Juan Rovalo

A regarded consultant, educator, and scientist with a passion for biomimicry—the practice of measuring and modeling human design solutions based on systems found in nature—Rovalo has over 20 years of experience contributing to hundreds of projects worldwide. Now, in his role as Director of Ecology for Perkins&Will, and in close collaboration with Jason McLennan, Juan works with project teams and clients to promote ecological thinking through the Perkins&Will “Living Design” approach.

Navya Raju & Juan Rovalo

Cites For All

Every urban planning project is related to wildlife; the only difference between a good, well-adapted one and a common one is that the latter chooses to ignore it.

At this moment, there are plenty of indications that our life-sustaining systems are unraveling, and undoing the damage will take generations. In the context of staggering numbers of wildlife lost (WWF), with seven of the nine safe operating planetary boundaries transgressed (Stockholm Resilience Center), and the trajectory of GHG emissions and the nation’s capacity to respond, we all should look for opportunities everywhere to address these compounding issues. Of course, this has to do with how we live and consume, but when it comes to biodiversity in urban and suburban spaces, we can recover ecological processes, functions, and values in every space we design.

There are many different frameworks we could use or get guidance and inspiration from, some people might respond to an ecosystem services approach, others to an ecosystem-based risk reduction model, nature-based solutions, mitigation hierarchies, ecosystem accounting, biomimetic solutions, biophilic design, environmental justice, nature positive, etc. While each approach differs in some ways, the general direction that all point towards is similar, not a single point on the horizon, but a close, adjacent section of it.

There is plenty of data showing our direct dependence on living systems in our economy, across all our productive sectors, and for our physical and mental health. It is clear that nature is our most valuable asset, and it is severely mismanaged.

It seems that, as a human community, we have limitations in understanding complex systems that operate over long periods and on large scales. The human realm mostly operates within a cultural system believed to be detached from ecological realities, which has led to an anthropocentric framework and the exclusion of non-human organisms from our economic discourse.

This limitation expresses itself through the diminished capacity to recognize the inherent interdependencies we have with the global ecosystem

When we do not consider nature and biodiversity in our design plans, we are damaging ourselves.

When the environment degrades, our own culture, well-being, and economies degrade.

So, should we give wildlife a place as stakeholders in our urban planning? Thinking that we are the ones who should give a place to wildlife still comes from a position of apparent superiority, in which we have something to give, out of our “brilliant generosity”.

We still frame our problems and solutions, addressing our relationship with nature and wildlife as if we were the ones who held authority over the rest of living organisms. As if we are the ones that can “give” rights, or “voice”, as if nature were dependent on our decision.

I would ask: what can we do in this ecosystem, through our projects, to improve its life-sustaining processes, functions, and values, for the benefit of all?

The lack of understanding of our dependency works against our own well-being, living in the illusion that we can create cities and systems with no reciprocal, positive relationship with our environment, and that everything will be ok in perpetuity.

This approach causes great harm to everyone. Many of the main diseases of our time have a direct relation to environmental degradation, pollution in our water, air, and food, and the spaces in which we work and live… and to major geopolitical issues, such as disease, famine, war, immigration, etc.

Every work, every project, every planning opportunity is related to nature, biodiversity, and our well-being.

Every urban planning project is related to wildlife; the only difference between a good, well-adapted one and a common one is that the latter chooses to ignore it.

about the writer

Reza Khan

Reza Khan is a Wildlife Biologist and Conservation Practitioner from Bangladesh with five decades of experience. He specializes in mammals, birds, human–wildlife conflict mitigation, and habitat restoration. His work covers forests, wetlands, and island ecosystems across Bangladesh. He has contributed to national and international journals, newspapers, and conservation reports. Reza is actively involved in community-based conservation, training, and conservation planning.

Reza Khan

Wildlife as a Stakeholder of Our Cities: A Bangladesh Perspective

Treating wildlife as a stakeholder does not mean prioritizing animals above people; it means acknowledging that ecological resilience underpins human resilience.

Cities are often imagined as purely human domains, yet their past and present tell a different story. When I first visited Dhaka in 1957, rhesus macaques still raided kitchens in the old neighbourhoods. Even earlier, in the 1800s and early 1900s, Dhaka’s outskirts supported tigers, leopards, Hispid hares, wild boar, marsh crocodiles, and abundant birdlife, as recorded in British-era gazetteers. By the mid-1900s, this megafauna had disappeared, leaving smaller species—civets, jackals, mongooses, fishing cats, macaques, squirrels, and bats are persisting in pockets of the growing city.

Today, Dhaka is one of the world’s most densely populated megacities, and its ecological base has eroded rapidly. Wetlands are filled, canals clogged, air choked by old vehicles, and informal settlements expand without basic services. Industrial effluents, solid waste, and construction pressure degrade the last remaining natural habitats. The situation in Chattogram, Khulna, Rajshahi, and Sylhet mirrors Dhaka’s trajectory.

The question for today’s roundtable is simple but urgent:

Can wildlife still be considered a stakeholder in our cities, or have we crossed the threshold where coexistence is no longer viable?

My answer is yes, but only if cities undergo a structural shift in how they plan, regulate, and imagine urban space. Treating wildlife as a stakeholder does not mean prioritizing animals above people; it means acknowledging that ecological resilience underpins human resilience. Many cities around the world—from Singapore to Amsterdam—are already integrating wildlife into planning systems. Bangladesh can do the same, but it requires targeted reforms, not abstract ideals.

- Establish Urban Biodiversity Governance

Dhaka urgently needs a dedicated Urban Biodiversity or Wildlife Office within DCC/RAJUK. This body should:

Represent wildlife interests during planning approvals, EIAs, and land-use decisions.

Ensure “no-net-loss” of habitat in development projects.

Set biodiversity standards for infrastructure, drainage, parks, and restoration sites.

Such an institution gives non-human life a formal, accountable place in city governance.

- Build a Citywide Biodiversity Map

Dhaka still retains wildlife in university campuses, botanical gardens, wetlands, old neighbourhoods, and institutional grounds. These isolated pockets must be inventoried and connected.

A city biodiversity map should:

Document ponds, canals, fragmented wetlands, and tree cover.

Identify ecological corridors and stepping-stones.

Guide zoning decisions and urban greening investments.

Connectivity—not isolated parks—is what allows species to move, forage, and reproduce.

- Design for Mobility, Habitat, and Food

Wildlife-friendly planning requires allowing animals to move safely across the urban matrix. Cities should:

Create green corridors along canals, rail lines, and wide roads.

Convert pocket parks, school grounds, and roadside strips into linked microhabitats.

Prioritize native trees, shrubs, and grasses that provide fruits, seeds, flowers, and cover.

Encourage green roofs, canopy retention, and pond preservation in building permits.

- Reduce Urban Ecological Stressors

Cleaner cities are safer for wildlife and humans. Key priorities include:

Controlling industrial effluents and open dumping.

Reducing emissions from old vehicles.

Managing plastic waste through community and municipal partnerships.

Healthy soil, water, and air are the foundation of urban biodiversity.

- Mobilize People and Technology

No strategy succeeds without public participation. Communities can lead through:

School biodiversity clubs, bird, and butterfly monitoring teams.

Neighbourhood wetland guardianship groups.

Citizen science apps, simple bird counts, and camera-trap monitoring.

Technology makes urban wildlife visible; participation makes it valued.

Bangladesh’s cities stand at a turning point. Wildlife can remain a stakeholder only if urban planning recognizes that ecological stability and human well-being are inseparable. Dhaka—and other growing cities—still have enough surviving pockets of green and blue space to rebuild an urban ecological network. The task now is to connect, protect, and expand these spaces through governance, design, and community action.

about the writer

Karina L. Speziale

Karina L. Speziale holds a PhD in Biology from the Universidad Nacional del Comahue. She is a CONICET Associate Researcher at GrInBiC, Conservation Biology Research Group of INIBIOMA (CONICET-UNCO) in the city of Bariloche. She teaches at the Universidad Nacional del Comahue in subjects and postgraduate courses related to ecology and biodiversity conservation. She participates in different advisory bodies as well as in numerous formal and informal environmental education activities on the importance of knowing and connecting with nature to assure valuing and protecting native biodiversity.

Karina Speziale

Decolonizing the Table: From Urban Colonizers to Biological Neighbors

They will be the cities where humans have finally remembered that they are not the landlords of the Earth, but members of a vast, living neighbourhood.

Some years ago, I came across the “BiodiverCities” concept, and it immediately came back to my mind when I received this invitation. It is a powerful framework, and I love it, but there are different approaches to achieving BiodiverCities around the world. On the one hand, we could consider that we are the owners of the cities, and we can invite wildlife to the planning table to foster coexistence, assuming the table is ours. Or we could consider that we are neighbours with wildlife, all having the same right to live in the same city. We can even go a step forward and see ourselves as the colonizers we are, the colonizers who have built urban success by seizing space and food from non-human life.

But there is a fundamental barrier to moving away from a colonizer approach. From birth, we are trained to be “social beings” within a strictly human vacuum. This social construct disconnects us from our essence: we are biodiversity. We are one species among many, depending entirely on the very life forms we have pushed away from cities. To move forward, we must decolonize our minds and our planning manuals. But we must do it from the beginning of our lives.

Science and technology as a Proxy for Voice

In my work within an urban wildlife monitoring network, I see human-wildlife tension daily. Despite living through a global crisis in the sciences, where funding and attention are scarce, it is precisely here—in the marriage of science and life—that we find a translator for those without a human voice, through the gathering of data.

Data is political. When we use cameras, bioacoustics, or citizen science to track urban species, we aren’t just doing science; we are gathering evidence to give a voice for those that are invisible to many urban citizens. In a world governed by citizens disconnected from wildlife and other forms of nature, data acts as a legal representative. It could be a way to transform wildlife from managed objects into our neighbours, with a measurable presence in the city’s budget and design.

The Necessity of Accepting Friction

However, giving wildlife a voice and creating BiodiverCities where human and non-human lives coexist requires us to embrace something humans usually hate: friction. We often want an ideal nature—pollinators that don’t sting or trees that don’t drop messy fruit, but true cohabitation is messy.

Like any human neighbor, wildlife can be annoying. They might rummage through trash, make noise at night, or claim spaces we wanted for ourselves. If we only accept nature that adheres to our dreams, or when it provides ecosystem services, we are still being utilitarian colonizers. A real neighbour has the right to exist even when we do not agree with their behaviour, or they don’t serve us. We need to design cities that aren’t just beautiful in a postcard sense, but resilient enough to handle or reduce the healthy, unpredictable friction of multi-species life coexistence.

Concrete Pathways

What does it take? It takes architects designing facades that are also nesting sites, and lawyers granting legal standing to urban rivers. But above all, it takes humility to recognize that the city is not a human property, but a shared habitat. We do not need to prepare a white canvas to start building a city, because it implies extra work: first, we remove wildlife, and then we bring nature back. But more importantly, because it is against justice.

And it also takes parents and teachers to educate a new generation of citizens. Not ones that are grown up as social beings with no nature etiquette, without a clue about how to interact with and live in nature, or the ones that only care for their human neighbours. We need a new generation of citizens with a deep connection with other forms of nature, and based on reciprocity, for nature and for their own well-being.

The BiodiverCities of the future will not be those that simply manage nature better. They will be the cities where humans have finally remembered that they are not the landlords of the Earth, but members of a vast, living neighbourhood. For that, we need to stop our own noise and disconnection long enough to hear wildlife through science, connection, design, and empathy.

Mark Hostetler

The Need for Model Developments and Parks that Explicitly Incorporate Wildlife Habitat

To have wildlife coexist with humans, people in cities must understand more about wildlife species, their behaviors, and their habitats.

How to give wildlife a voice? One way is to provide living space (wildlife habitat) for a variety of species. From my experience, the best way to do this is to create model subdivisions or common areas (such as city parks) that incorporate designs and management practices that benefit wildlife. Designs could include such things as native plants in landscaped yards, the conservation of more “wild” areas in a development and a city, the use of shielded lights that limit light pollution, and the design of roadways that slow traffic down or are placed to provide wildlife corridors. Management could be concentrated efforts to reduce lawn irrigation (that could carry pollutants to nearby waterbodies), the removal of invasive plants, and even prescribed burns for nearby natural areas. But how to change conventional ways of thinking and adopt new strategies to promote wildlife habitat?

An important step is to find that maverick developer (and maverick policy maker) who is willing to incorporate and to encourage wildlife habitat into a development design. City planners could include policy “carrots” that reward a developer that conserves wildlife habitat (e.g., reduction in permit costs). This developer and the unique policies that go along with the alternative development pave the way (no pun intended) for future development that includes wildlife habitat. Further, the creation of parks with wildlife habitat demonstrates and creates opportunities for other parks to adopt wildlife habitat conservation practices.

But of course, to have wildlife coexist with humans, people in cities must understand more about wildlife species, their behaviors, and their habitats. Residents must be on board in terms of understanding the goals of living with wildlife. A subdivision with protected wildlife habitats must have a management/educational program for the entire community that addresses the intricate connections between wildlife habitat and human-dominated areas (i.e., think of the impacts of an invasive plant installed in a yard). The health of these natural areas is intricately tied to the behaviors of nearby residents. With wildlife habitats nearby, developers and policymakers need to install some sort of visible educational program that addresses how local neighborhood actions affect spaces for wildlife.

Further, it is important to show that a design or management practice can benefit both wildlife and humans. For instance, for wildlife, conserving the tree canopy can benefit migrating birds as well as many other species. For humans, tree canopy conservation reduces stormwater flow by intercepting a portion of the rain when it hits leaves, branches, and trunks. This can be a significant savings; for example, in the metropolitan Washington DC region, the existing 46 % tree canopy reduces the need for stormwater retention structures by 949 million cubic feet, valued at $4.7 billion per 20-year construction cycle (based on a $5/cubic foot construction cost). Further, most homeowners view green areas within close proximity to homes as aesthetically pleasing. This translates to an economic value of green space.

Do not underestimate the power of a local example. Nothing speaks more to increasing the uptake of alternative designs and management practices (for wildlife) than examples that people can see and discuss. I have found building that first local conservation subdivision helps to showcase green development practices and provide a catalyst for future developers and planners to adopt new practices for wildlife.

about the writer

Haseeb Irfanullah

Dr. Haseeb Md. Irfanullah is a biologist-turned-development facilitator, who often introduces himself as a research enthusiast. Over the past 27 years, Haseeb has been working for different international environmental and development organizations, academic/research institutions, donors, and government agencies in different capacities.

Haseeb Irfanullah

The unique aspect of NbS is that it simultaneously supports human wellbeing and biodiversity benefits.

Giving wildlife “an actual place at the discussion table” or “a voice in how we plan and design” our cities, or calling wildlife a “stakeholder” of urban planning decisions, is indeed a romanticist attempt to underscore nature’s importance in the built environment. But, how can this tremendous urge of inclusion be materialized, so that it doesn’t remain a mere dream?

Building on my country, Bangladesh’s recent experience, I see two ways to do that. First, when we conduct spatial planning at national, sub-national, or local levels, we are supposed to consider ecological spaces by default, since we all live in social-ecological systems. Just imagine Bangladesh with respect to the world’s biodiversity. For its global positioning, we must consider the globally significant Ramsar sites it has (i.e., the Sundarbans Mangrove Forest in the south-west, and Tanguar Haor wetland in the north-east), the UNESCO World Heritage Site it cherishes (once again, the Sundarbans), and the south-central region of Bangladesh, which is FAO’s Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems, for example. From a regional positioning, Bangladesh is located at the crossroad of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway and the Central Asian Flyway of migratory birds. The country’s terrestrial and marine protected areas, key biodiversity areas, and ecologically critical areas are part of its national biodiversity positioning. Like the national positioning, the sub-national positioning (e.g., village common forests and private/community-based conservation areas) is governed by national policies, laws, rules, regulations, strategies, and action plans. For the first two positionings, global multilateral environmental agreements and bilateral treaties are crucial guiding instruments. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s first target expects participatory, integrated, and biodiversity-inclusive spatial planning to stop biodiversity loss. More specifically, Target 12 highlights biodiversity-inclusive urban planning for sustainable urbanization. As a subset of local spatial planning, urban planning is therefore supposed to adopt biodiversity conservation to align with the host country’s global pledges. Capitalising on this global commitment, the advocates of spatial planning in Bangladesh have recently convinced the government to pass the Spatial Planning Ordinance, 2025, in November 2025. This outstanding milestone has given a legal base to the urban planning-biodiversity conservation integration.

Second, from a climate resilience point of view, Nature-based Solutions (NbS) as a concept have been strongly integrated into Bangladesh’s National Adaptation Plan (2023-2050). NbS are those actions that harness ecosystem services to address different societal challenges, such as climate change. The unique aspect of NbS is that it simultaneously supports human wellbeing and biodiversity benefits. In 2016, NbS started gaining momentum, which reached a peak during the COVID-19 Pandemic through the publication of IUCN’s global standard for NbS (2020). Subsequently, 2022 saw NbS being recognized by the United Nations’ Environment Assembly (February), climate change (November), and biodiversity (December) conferences of the parties. In the same year, the Bangladesh NAP also made NbS one of its six goals (Goal 4: Promote nature-based solutions for the conservation of forestry, biodiversity, and the well-being of communities). But, NbS is not only planting trees and guarding forests led by foresters and environmentalists. The NAP’s goal on urban resilience (Goal 3: Develop climate-smart cities for an improved urban environment and wellbeing) also has provisions to integrate NbS actions in urban flood and stormwater management, integrated water management, and conservation of green and blue infrastructure, for example, which would recreate homes for the wildlife.

The examples from Bangladesh, a country of 70 million urbanites, show that with proper thought and action leadership, global concepts can be contextualised into national laws, policies, and projects to embrace wildlife for urban planning.

about the writer

Peter Edwards

Peter is a senior researcher in political science and sociology at the New Zealand Bioeconomy Science Institute. Peter works on a wide range of topics, including public perceptions of the environment, narratives and discourses, serious games, and nature-based solutions for urban and climate health.

Peter Edwards

Should wildlife be a stakeholder in urban planning?

While wildlife unequivocally belongs “at the table” of urban planning and policy, there is work to be done at governance, logistical, and individual values and worldviews levels.

I’ll start by stating unequivocally that wildlife should be considered a stakeholder in urban planning and policy. To me, this consideration of including wildlife as a stakeholder in urban planning decisions is connected to the “bigger picture” of the ongoing global shift from government to governance. This shift has, in many ways, promoted the inclusion of a wider range of stakeholders in governing, and there is no reason to exclude wildlife. As nature-based-solutions become increasingly implemented in our urban centres, it follows that wildlife will become more prevalent and should have a similar right to life and “enjoyment” of their “home” and environment as humans.

When we look at the practicalities of including wildlife as stakeholders, the logistics can become a bit trickier. While there is a body of evidence that wildlife are sentient and can, and do, express preferences regarding their environment, we don’t necessarily have the mechanisms nor the skills to communicate effectively with them. As the prompt rightly points out, providing wildlife with a voice through data, design, and policy negates the need for direct communication. However, the use of human-developed data and designs raises questions around how well these data and designs consider the needs and wants of wildlife versus what humans think they need and want. The interests, influence, and exercise of power by human stakeholders over wildlife will need to be held in check.

While these last thoughts may sound rather pessimistic, there is some hope for recognising the needs of more-than-human stakeholders. In 2008, Ecuador included the environment in its constitution, Aotearoa New Zealand gave legal personhood to Te Urewera (a forested region), the Whanganui River, and Taranaki Maunga (a mountain and its surrounding environment) in 2014, 2017, and 2025 respectively, and the Gouda Municipality in the Netherlands has given nature a permanent opportunity to “participate” in urban planning decision. Drawing on the learnings of what has, and has not, worked well with the recognition of such more-than-human stakeholders could inform suitable ways to include wildlife as an urban stakeholder in planning and policy.

Outside of the more pragmatic aspects above, we need to consider the role of urban human residents’ perceptions, values, beliefs, and worldviews. In the little research that has been conducted, urban residents appear to perceive wildlife as an anxiety-inducing nuisance, a perception that facilitates humans’ continued “management” of wildlife. A critical step towards making space for wildlife as a stakeholder is, therefore, to develop and influence a more positive relationship between urban residents, nature, and wildlife.

A reshaping and reframing of human narratives about our own place in urban and wider ecosystems, as well as our entrenched, and too often negative, worldviews of urban wildlife, is required. By understanding these narratives and the work they are doing, we gain the potential to:

- Influence and reinforce our sense of ourselves, our sense of place, and our sense of our own relationships to others – human and non-human.

- Establish and adjust our multi-species connections, relationships, power dynamics, belief systems, and worldviews.

- Justify, validate, and direct which practices we take up and which we do not.

Our narratives (the stories we tell ourselves and others) are therefore interwoven with our worldviews and our practices in ways that mutually inform and reinforce each other. Narratives can shape, challenge, and/or expand our worldviews and identities, and thus they hold the potential to shift our practices. Thus, if we want to influence other people’s practices, we need to recognise that such practices are not only determined by logistical factors, but are also shaped by narratives, identities, and worldviews.

While wildlife unequivocally belongs “at the table” of urban planning and policy, there is work to be done at governance, logistical, and individual values and worldviews levels. This work can’t be done by ecologists or economists or planners or social scientists alone but requires a strong inter- and transdisciplinary approach that includes the stakeholders themselves with the ecologists, planners, policymakers, economists, and social scientists.

Some references that have guided my thinking:

Akchurin, M. 2015. Constructing the Rights of Nature: Constitutional Reform, Mobilization, and Environmental Protection in Ecuador. Law & Social Inquiry, 40(4): 937–968. doi:10.1111/lsi.12141.

Basak, S.M., M.S. Hossain, D.T. O’Mahony, H. Okarma, E. Widera, I.A.Wierzbowska 2022. Public perceptions and attitudes toward urban wildlife encounters – A decade of change. Sci. Total Environ., 834: 155603, 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155603.

Gosnell, H. 2022. Regenerating soil, regenerating soul: an integral approach to understanding agricultural transformation. Sustain Sci 17: 603–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00993-0

Goudasepost. 2025. Gouda geeft natruur als eerste gemeente een vaste plek in part [ Gouda is the first municipality to give nature a permanent place in participation].

Hargreaves-Méndez, M., Gordon, E., Gosnell, H. et al.2025. Human-animal relations in regenerative ranching: implications for animal welfare. Agric Hum Values 42: 3041–3060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-025-10798-x.

Sanders, K. 2018. ‘Beyond Human Ownership’? Property, Power and Legal Personality for Nature in Aotearoa New Zealand, Journal of Environmental Law, 30(2): 207–234. https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqx029

about the writer

Seth Magle

Seth Magle is the Director of the Urban Wildlife Institute at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago, Illinois. He has studied wildlife in urban areas for nearly twenty years.

about the writer

Kimberly Rivera

Originally from the suburbs of New York City, I have been lucky to call many places my home to support conservation and research initiatives globally. I am excited by interdisciplinary research and partnerships which bridge science to integrative conservation solutions. My primary research focuses on long-term biodiversity monitoring, wildlife habitat use and connectivity, and assessing anthropogenic impacts on ecological systems.

Seth Magle & Kimberly Rivera

To give wildlife a seat at the planning and design table, we are going to have to build a shared understanding of each part that forms the whole of the cities, including their history, culture, and ecology.

Though cities were built for humans, they were never wildlife-free. Our oldest records of cities mention rats, seemingly every bit as at home as the city’s people were. In North America, animals like squirrels and pigeons are so common that many people don’t even perceive them as wildlife.

So, the question is not; will we live with wildlife, or even will we coexist with them? We already do, and we will continue to, no matter what choices we make. There is a misconception that if we ignore wildlife in our cities, we simply won’t have any, but nothing could be further from the truth. The question is what species will we share our cities with―or in other words, what wildlife will we represent at the decision-making table?