Kathleen Watts’ flowers bloom much brighter now that the wind no longer blows black. Pulling weeds in the garden outside her redbrick house, she recalled when coal dust would sometimes drift through her quiet corner of northern England, a rolling patchwork of farms and villages under the shadow of what was once the United Kingdom’s largest coal-burning power station.

“When the dust came our way, we’d have to come out and clean our windows,” said Watts, who has lived in the North Yorkshire village of Barlow for more than 30 years. “And when we’d get snow in winter, there’d be a lot of black over it.”

Thankfully, she said, the wind usually blew northeast, pushing the station’s smoke and dust toward Scandinavia. Locals liked to joke that the air pollution was mostly Norway’s problem. There, it caused bouts of acid rain that damaged forests and poisoned lakes.

The U.K. has quit coal — a lengthy process culminating in the closure of the country’s last deep-pit coal mine in 2015 and the shutdown of the U.K’s last coal plant in 2024.

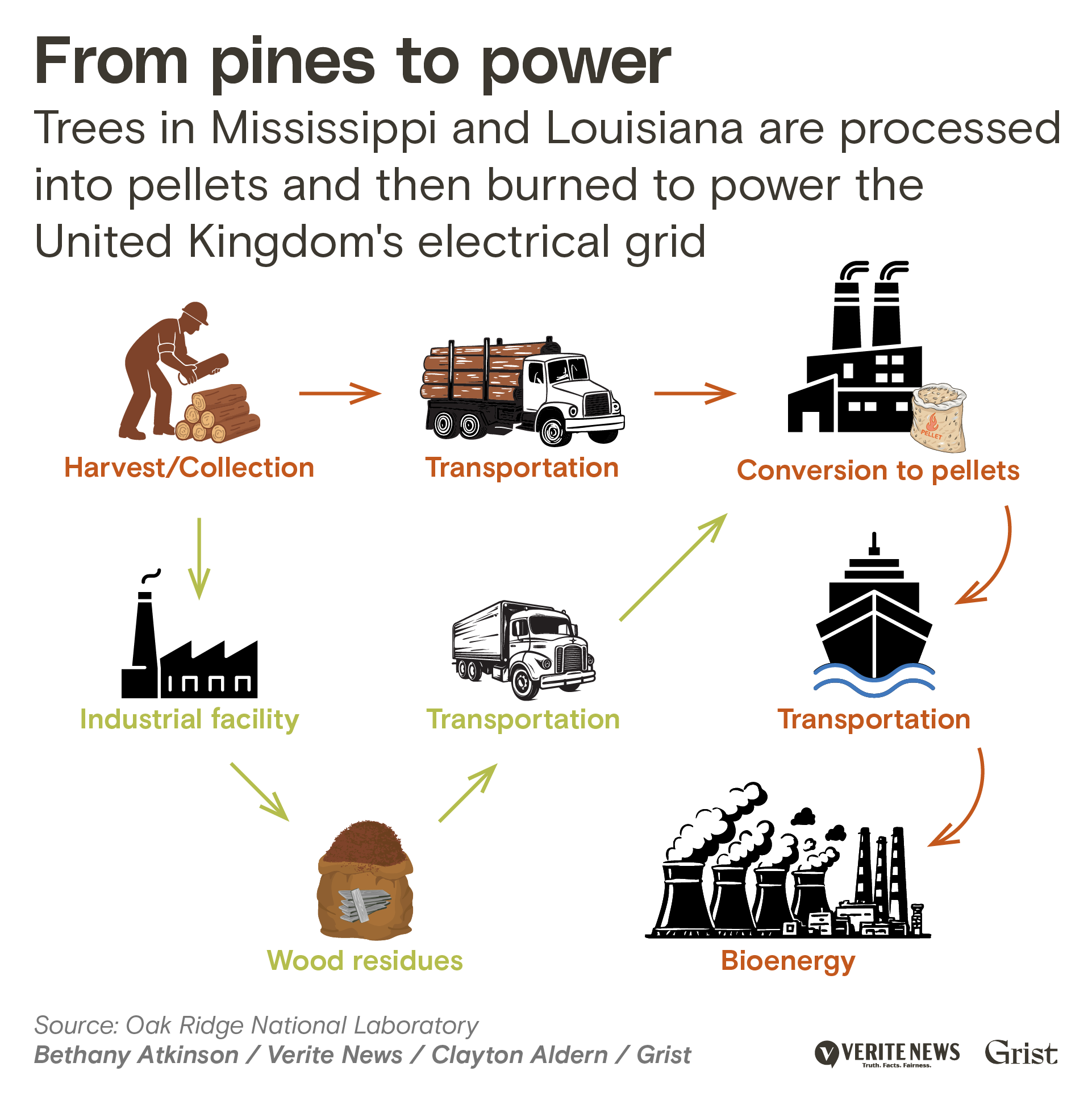

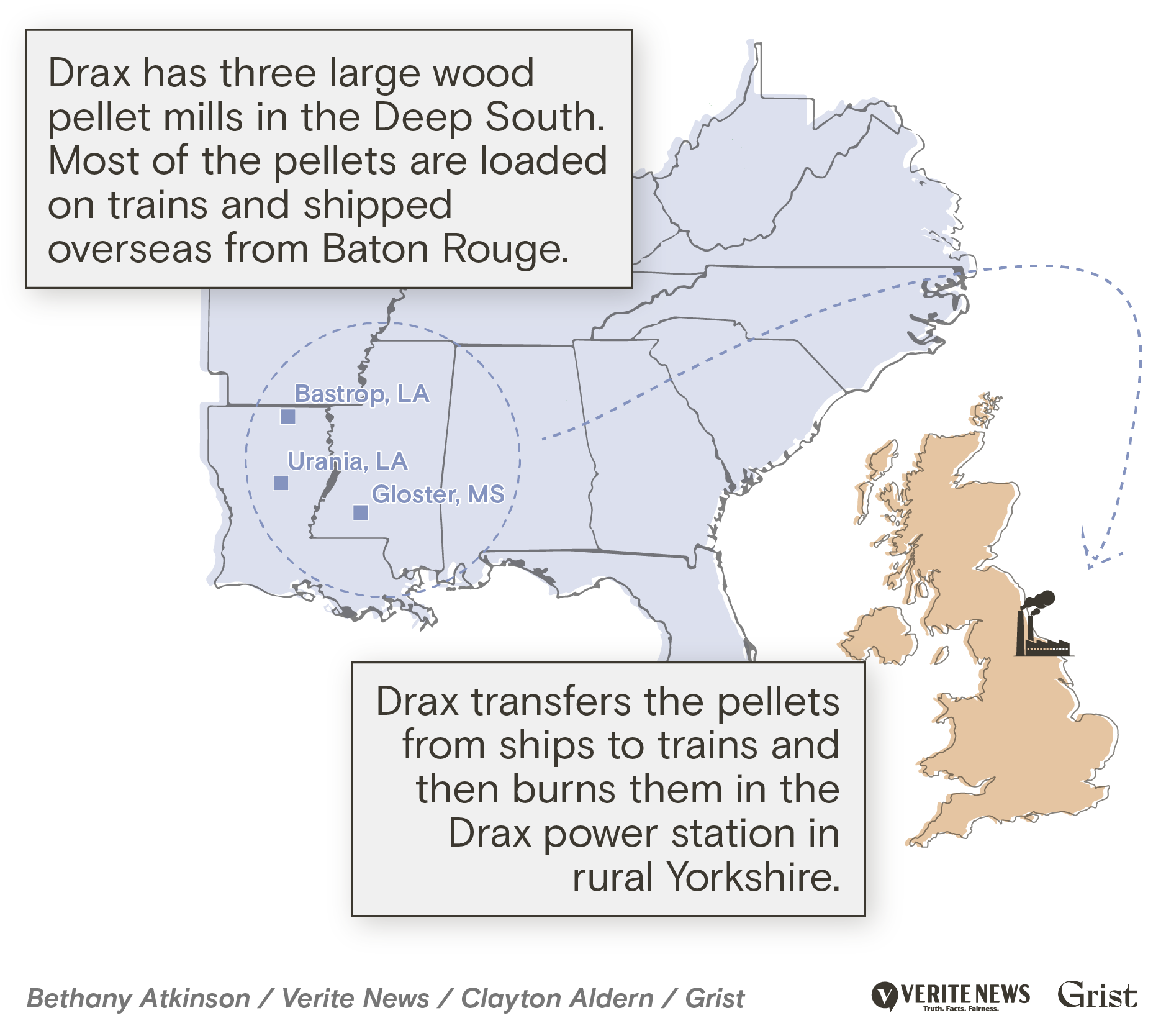

The giant station near Barlow, however, is busier than ever, fueled now by American forests rather than English coalfields. Trees felled, shredded, dried, and pressed into pellets in Louisiana and Mississippi are shipped across the Atlantic Ocean, loaded onto trains, and then fed into the station’s immense boilers. Operated by Drax Group, the station gradually stopped burning coal until it made a full switch to wood in 2023. It now burns enough pellets to generate about 6 percent of the country’s electricity.

Tristan Baurick / Verite News

The U.K. government, in a bid to meet its ambitious climate goals, is giving Drax the equivalent of $2.7 million a day in subsidies to keep burning pellets, which the company touts as “environmentally and socially sustainable woody biomass.”

But a growing number of Brits aren’t buying it. After years of celebrating the shift away from coal, U.K. residents are realizing that wood pellets aren’t the cleaner, greener alternative they were supposed to be.

“I still have difficulties in my little brain figuring out how you can grow wood at the other end of the Earth, chip it, ship it to here … and then burn it, and say, ‘Isn’t that nice and green?’” said Steve Shaw-Wright, a former coal miner who serves on the North Yorkshire Council.

Burning wood for power instead of one of the dirtiest fossil fuels offers the illusion of sustainability and robust climate action, said William Moomaw, an emeritus professor of international environmental policy at Tufts University. But in reality, it’s doing more harm to the environment than burning fossil fuels, he said. “England is off coal — isn’t that wonderful?” Moomaw said. “But there’s no mention of the fact that it’s because they’re now burning wood from North America, which emits more carbon dioxide per kilowatt of electricity than does coal.”

Eric J. Shelton / Mississippi Today

The Drax station in North Yorkshire emitted more than 14 million tons of carbon dioxide in 2024, making it the largest single source of CO2 in the U.K., according to a report last year from the climate research group Ember. That amount is more than the combined emissions from the country’s six largest gas plants and more than four times the level of the U.K.’s last coal plant.

A Drax spokesperson called Ember’s research “deeply flawed” and accused the group of choosing to “ignore the widely accepted and internationally recognized approach to carbon accounting,” which is used by the United Nations and other governments.

But several scientists say burning wood can’t help but produce more emissions. Wood has a lower density than coal and other fossil fuels, so it must be burned in higher volumes to produce the same amount of energy. Between 2014 and 2019 — a period when coal was in steep decline — the country’s CO2 emissions from U.S.-sourced pellets nearly doubled, according to a report by the Chatham House research institute in London. “Almost all of this U.K. increase was associated with biomass burnt at Drax,” the report’s authors wrote.

The station’s cross-continental supply chain is also heavy on emissions. For every ton of pellets Drax burns, about 500 pounds of CO2 are released just from making and transporting the product, according to Chatham House. About half of Drax’s supply chain emissions are tied to production, while transportation via trucks, trains, and ships accounts for 44 percent, according to the company’s estimates.

The switch from coal to pellets created a new pollution problem in Louisiana and Mississippi, where most of the station’s fuel is produced. Drax’s pellet mills have repeatedly violated air quality rules at its two Louisiana mills, located near Bastrop and Urania, and its mill in Gloster, Mississippi. The mills emit large quantities of formaldehyde, methanol, and other toxic chemicals linked to cancers and other serious illnesses, according to regulatory findings and public health studies. Residents of these poor, mostly Black communities say the mills’ dust and pollution are making them sick. In October, several Gloster residents sued the company, alleging that Drax has “unlawfully released massive amounts of toxic pollutants” in their community for nearly a decade.

The Drax spokesperson said the company is improving its mills’ pollution controls in line with a longstanding dedication to “high standards of safety and environmental compliance.” On its website, Drax says the company is “committed to being a good neighbor in the communities where we operate,” offering funding for environmental education programs, ensuring its wood is sourced from “well-managed forests,” and supporting land conservation efforts, including the establishment of a 350-acre nature reserve near Watts’ home in Barlow.

Much of the timber that Drax harvests comes from private lands in the Southern United States that function more as tree farms than natural forests. But in recent years, Drax has sourced an increasing share of its wood from western Canada, including from British Columbia’s treasured old-growth forests.

In 2024, Drax agreed to pay a nearly $32 million penalty after U.K. energy regulators determined the company had been misreporting data on where it sources its wood and how much of it comes from environmentally important woodlands. The practice of pelletizing Canada’s mature trees appears ongoing, according to a recent report by the environmental group Stand.earth. Citing logging data from 2024 and 2025, the group claims Drax has been accepting truckloads of trees from British Columbia that were hundreds of years old. Drax downplayed the report, emphasizing that the logs were legally harvested and of insufficient quality to go to sawmills.

Drax sees itself as one of the most environmentally conscious companies on the planet. “Sustainability is the cornerstone of long-term success and the transformation of our business,” said Miguel Veiga-Pestana, Drax’s chief sustainability officer, in a statement.

While most pellets Drax makes in the U.S. are derived from logged trees, the company also uses sawdust and other leftovers from lumber mills. The company supports forest thinning, a practice it says can ease crowding in densely planted timberlands, improve the health of the remaining trees, and diversify habitat for wildlife.

“By ensuring that we source sustainable biomass, and that we embed sustainable practices into every facet of our operations, we can build lasting value,” Veiga-Pestana said.

The value of the entire utility-scale wood pellet industry depends on what many scientists call an “accounting loophole” entrenched in some of the earliest international policies aimed at combating climate change.

During the 1990s, the United Nations’ Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol established land use and energy use as two separate categories for counting a country’s greenhouse gases. To avoid double counting wood burning across both land-use and energy-use categories, the U.N. assigned wood pellet emissions only to the land-use sector, believing that normal forest regrowth would keep pace with the modest harvests for pellet production. The wood pellet industry at the time was tiny, selling the bulk of its products to homeowners with small pellet-burning stoves. Any carbon released by burning would be balanced by new trees that work as natural CO2 absorbers, the thinking went.

The effect, though, was that regulators would count CO2 from burning oil and coal, but CO2 from burning timber could stay off the books.

“Drax and other bioenergy companies took that and said, ‘Look, we have no impact — we’re instantly carbon neutral,’” said Mary Booth, director of the environmental organization Partnership for Policy Integrity.

This exemption was incorporated into the Kyoto Protocol, the first international treaty that set legally binding greenhouse gas reduction targets. Experts were soon warning of troubling consequences. In a study published in the journal Science in 2009, scientists said the exemption was an “accounting error” that could spur deforestation and hinder attempts by governments to curb emissions.

“The error is serious, but fixable,” said Tim Searchinger, a Princeton University energy policy expert, in a statement at the time. “The solution is to count all the pollution that comes out of tailpipes and smokestacks whether from coal and oil or bioenergy, and to credit bioenergy only to the extent it really does reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

Other scientists challenged the industry’s claim that planting trees would neutralize power station emissions. According to a study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, it can take 44 to 104 years for forest regrowth to pay back the carbon debt from pellet burning. While the planet waits decades for the trees to regrow, glaciers melt, seas rise, and weather from droughts to hurricanes grows more extreme.

Kathleen Flynn / The Guardian

Despite these warnings, the European Union latched on to wood burning as a relatively quick and cheap way to meet tighter climate mandates. Rather than blanket the landscape with wind turbines and solar panels, countries could dust off old coal plants and put them on a diet of “carbon-neutral” pellets.

The shift toward bioenergy accelerated in 2009, when the European Union set a target of getting 20 percent of its energy from renewables by 2020. Pellet demand in Germany, Belgium, Italy, and other European countries immediately began to increase, but in the U.K., the growth was explosive. Between 2012 and 2018, the U.K.’s pellet consumption surged by 471 percent, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The U.K. left the European Union in 2020, and it remains the world’s biggest buyer of wood pellets. In 2024, the country imported nearly 10.3 million tons, a record high spurred partly by a dip in pellet prices.

Wood burning has helped the U.K. come within striking distance of its goal to eliminate oil and gas from its electrical generation by 2030. Nearly 74 percent of the national grid is powered by what the government calls “low carbon” energy sources. Wood pellets and other forms of bioenergy supply about 14 percent of the low-carbon mix, with wind, solar, and hydropower accounting for the rest.

Every workday, Ian Cunniff climbs into his orange overalls, pounds his helmet tightly on his head, and steps into a cage that drops 459 feet into a maze of dark tunnels littered with old machinery.

The stout Yorkshireman is one of the last miners still working in the coal pits, but now his job is to lead tours along the rich seams he once risked his life to dig out. Cunniff is a guide for the National Coal Mining Museum at Caphouse Colliery, a former West Yorkshire mine dating back to the 1790s. His last “real” mining job was at Kellingley Colliery, the U.K.’s last deep coal pit and a major feeder of Drax’s power station before it switched to wood.

In the depths of the Caphouse mine, Cunniff grew wistful over the coal still embedded in the walls. The seams once provided nearly everything a man and his family needed, he said. “It was your future; it was your retirement. So much of it has never been touched.”

Christopher Furlong / Getty Images

Wood pellets didn’t kill the U.K.’s coal industry. It began to wither as the country shifted from cheaper, imported coal in the 1980s to natural gas in the 1990s. Coal’s decline left gaping holes in Yorkshire’s economy and social fabric. The wood pellet industry has contributed some jobs and tax dollars, but it can’t replace what the region once had, said Shaw-Wright, the county council member.

“With coal, you didn’t really need to get an education much because you were going to get a job at the pit,” he said. “And if you had a job at the pit, you would have it for life.”

At its height between the two world wars, the industry employed 1.2 million people in the U.K. In some northern England counties, 1 in 3 residents was employed in coal mining. The Selby Complex, a group of deep-pit mines near the Drax power station, employed about 3,500 workers before it shut down in 2004. The industry also supported cooperative groups that funded social halls, community brass bands, libraries, sports clubs, and welfare programs for injured miners and their families.

In contrast, the Drax-dominated bioenergy industry employs about 7,400 people across the U.K., including about 1,000 people at the Drax station. The increasingly automated industry has seen its job numbers fall by more than a third since 2014, according to data from the U.K.’s Office of National Statistics.

A similar trend is playing out in Louisiana and Mississippi, where the three Drax wood pellet mills employ far fewer people than the older pulp and paper mills that once played a dominant role in the Deep South. The paper mill in Bastrop, for instance, once employed 1,100 people. Drax’s pellet mill near the town has just 71 workers on its payroll.

Shaw-Wright appreciates the economic activity the wood pellet industry brings to Yorkshire but said most of the region’s recent job growth actually comes from a surge in distribution centers for online retailers — a trend that has turned Yorkshire into the country’s “capital of warehousing.” Many of these massive facilities now sit on former coal fields, including the old Kellingley Colliery, yet the work of unloading and sorting parcels doesn’t provide the pay, stability, or sheer number of jobs that mining once did.

After giving another tour, Cunniff rested in the colliery’s old locker room. He knows coal isn’t coming back, but he doesn’t believe cutting and burning trees to power the grid is any better — for Yorkshire or the planet.

“So you’re taking away what’s cleaning the atmosphere, and you’re burning it?” he said. “That’s the big picture, isn’t it?”

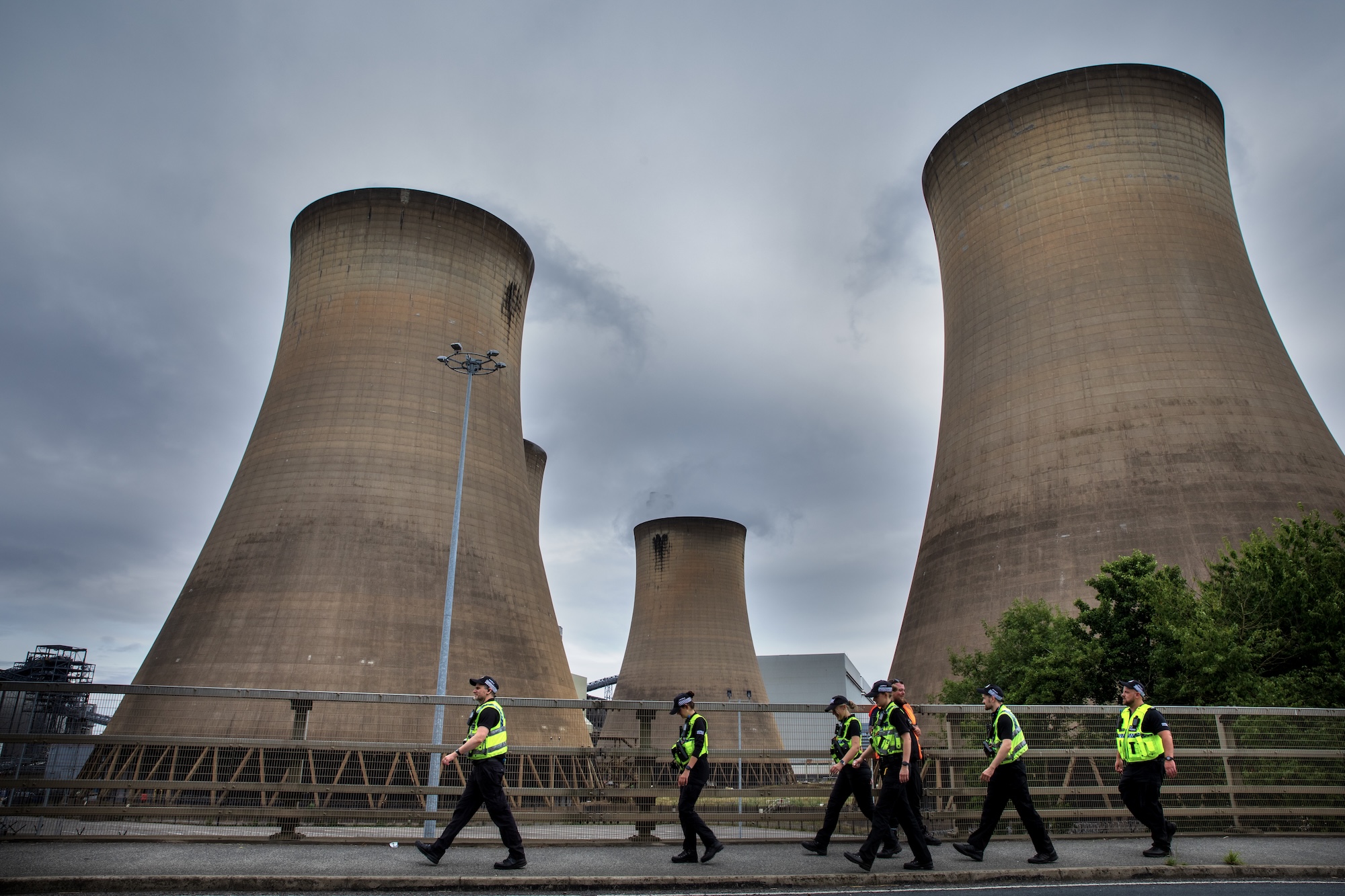

The Drax power station is the dominant feature across several miles of North Yorkshire countryside. Its 12 cooling towers are each big enough to hold the Statue of Liberty. Every day, about 17 trains full of pellets arrive to top off four storage domes with a combined 360 million-ton capacity. The pellets are pulverized as fine as flour and blown into several boilers. Stored in hangar-like structures in the station’s center, the boilers consume some 8 million tons of pellets each year with fires that reach 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit.

Just outside the station’s 3 miles of razor-wire fencing is a village, also called Drax, with one tiny pub. Inside, there was little love for the big neighbor.

“They’re taking wood from where they shouldn’t be taking it,” Tony Emmerson said as he sipped a beer at The Huntsman’s bar. “I think we should go back to coal, personally. We’ve got a hundred years of coal right here just waiting to be burned.”

Many of Drax’s post-coal era promises — lower energy bills, cleaner air, and a decarbonized grid — have proven hollow, Emmerson said.

“They get all this tax money but we don’t get cheaper power bills,” said Peter Rust, The Huntsman’s owner. “And they say they’re carbon neutral, but how’s that possible when you have to bring the pellets across an ocean?”

Gary Calton / The Guardian

The growing doubts about the wood pellet industry are seeping into public debate, leading the government to rethink its support for Drax. Last February, Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s government decided that the current subsidies for Drax would be cut in half in 2027. The subsidy renewal, which lasts until 2031, also requires Drax to increase the proportion of “sustainably sourced” biomass from 70 percent to 100 percent. Michael Shanks, the energy minister, told Parliament that the government made the move because Drax was making “unacceptably large profits” and “simply did not deliver a good enough deal for bill payers.”

Shanks, however, emphasized that wood pellets will still play a key role in powering the U.K.’s grid, and he welcomed Drax’s new efforts to bolster its green credentials. That includes a massive investment in carbon capture and storage technology. For years, Drax has been planning a pipeline that would divert about 8.8 million tons of the station’s CO2 emissions into storage under the North Sea. Reduced subsidies, though, are likely to slow these projects, the company has warned.

Many Yorkshire residents knew exactly — and proudly — where the Drax station’s coal came from. They’re much less sure about where the wood is sourced. Watts, the gardener in Barlow, assumed the trees were grown on English farms. Shaw-Wright was also far off the mark, thinking the pellets came from Australia. At The Huntsman, guesses were slightly closer, with people calling out South America and Eastern Europe — regions that together supply only 10 percent of the station’s fuel. The fact that the U.S. meets nearly 80 percent of the station’s demand was a surprise to many.

Environmental groups, meanwhile, have been campaigning for a broader understanding of the industry’s impacts. U.K.-based Reclaim the Power and Biofuel Watch have been highlighting the concerns about emissions as well as the pollution affecting mill towns in Mississippi and Louisiana.

Several groups had planned to stage a large protest outside the Drax station in August 2024. Drawing hundreds of activists from around the country, the “Drax Climate Camp” was to feature five days of “communal living and direct action.” But police preemptively arrested 25 protesters and halted a convoy of vehicles carrying tents, composting toilets, wheelchair-accessible matting, and other gear. Activists staged a much smaller protest outside the police station where their fellow campaigners were held, but the groups decided the camp couldn’t continue without the equipment.

Climate protesters hold signs outside a police station in York, England, in August 2024. Several of their fellow activists were arrested during preparations for a protest near the Drax power station in rural Yorkshire.

Gary Calton / The Guardian

Police patrol outside the Drax power station in Yorkshire. Dozens of officers were called to the station in 2024 to prevent a planned protest encampment.

Gary Calton / The Guardian

The aborted protest got Shaw-Wright thinking more about the connection between the pellet mills in the Deep South and the electricity that lights his home.

“Louisiana, that’s where they make the ‘gumba’ and they love cooking crocodiles, right?” Shaw-Wright said, half joking. “I think people will be surprised where the wood comes from and … know nothing of how it’s produced or what it entails. We need to be educated more about the communities that, in essence, benefit the Drax power station. And we all benefit from it. But if it’s at the expense of others, it gives you a different perspective.”

Rust, the pub owner, wasn’t so reflective, but he was deeply disappointed the camp was quashed. “I thought we were going to get loads more customers,” he said. “I bought loads more bottles when I heard about it. I thought finally Drax was going to do some good for me.”