Michigan might be at the forefront of a new clean fuel source — and it’s buried right under the state.

Last month, Governor Gretchen Whitmer said her administration wants to make the state a hub for geologic hydrogen, a potentially untapped reserve of clean fuel below the Earth’s surface that could power the transition away from fossil fuels.

The U.S. already produces millions of tons of hydrogen a year to power carbon-intense transportation sectors like heavy trucking and shipping, but it’s expensive and requires a lot of energy. Harnessing natural hydrogen could bring prices down and cut more emissions from those industries.

Here’s what to know about this potential new source of clean energy:

How does hydrogen form within the Earth?

There are several ways that large amounts of hydrogen may have formed within the Earth’s crust, according to Matt Schrenk, a geomicrobiology professor at Michigan State University. Scientists know that deposits of natural hydrogen are created when water reacts with iron-rich rocks. Another way hydrogen forms is when certain rocks decay over the course of millions to billions of years, but research hasn’t shown it can result in large stores. One theory suggests that hydrogen has been continuously seeping from the Earth’s core since the planet formed 4.5 billion years ago.

Because all of this occurs deep inside the Earth, naturally occurring hydrogen isn’t easy to get to without drilling.

C. Bickel / Science (graphic); Geoffrey Ellis / USGS (data)

Why is Michigan a good place to look for it?

A 2025 study from the U.S. Geological Survey, or USGS, mapped out areas around the country with a lot of potential for buried hydrogen, with Michigan identified as a bright spot. That’s because the state sits on top of what’s called the Midcontinent Rift. It’s where the North American continent started splitting apart more than 1 billion years ago, then stopped.

“This represents, potentially, a pathway for which deep hydrogen can come up closer to the surface and be collected and extracted,” Schrenk said.

As for possible hot spots beneath the state, think of Michigan’s lower peninsula like a giant bowl — it’s called the Michigan Basin for this reason. The younger, newer rocks are typically in the center of this bowl in the middle of the state. Deeper, older material — places where hydrogen might have formed — is found closer to the bowl’s edges, where Detroit and Traverse City are situated today.

Still, the authors of the USGS study noted that much of the hydrogen they outlined is likely “too deep, too far offshore or in accumulations too small to be economically recoverable.”

Besides Michigan, the USGS study pointed to areas like southern Oklahoma and northeastern Kansas that similarly might be sitting on large reserves of geologic hydrogen.

What is the climate connection?

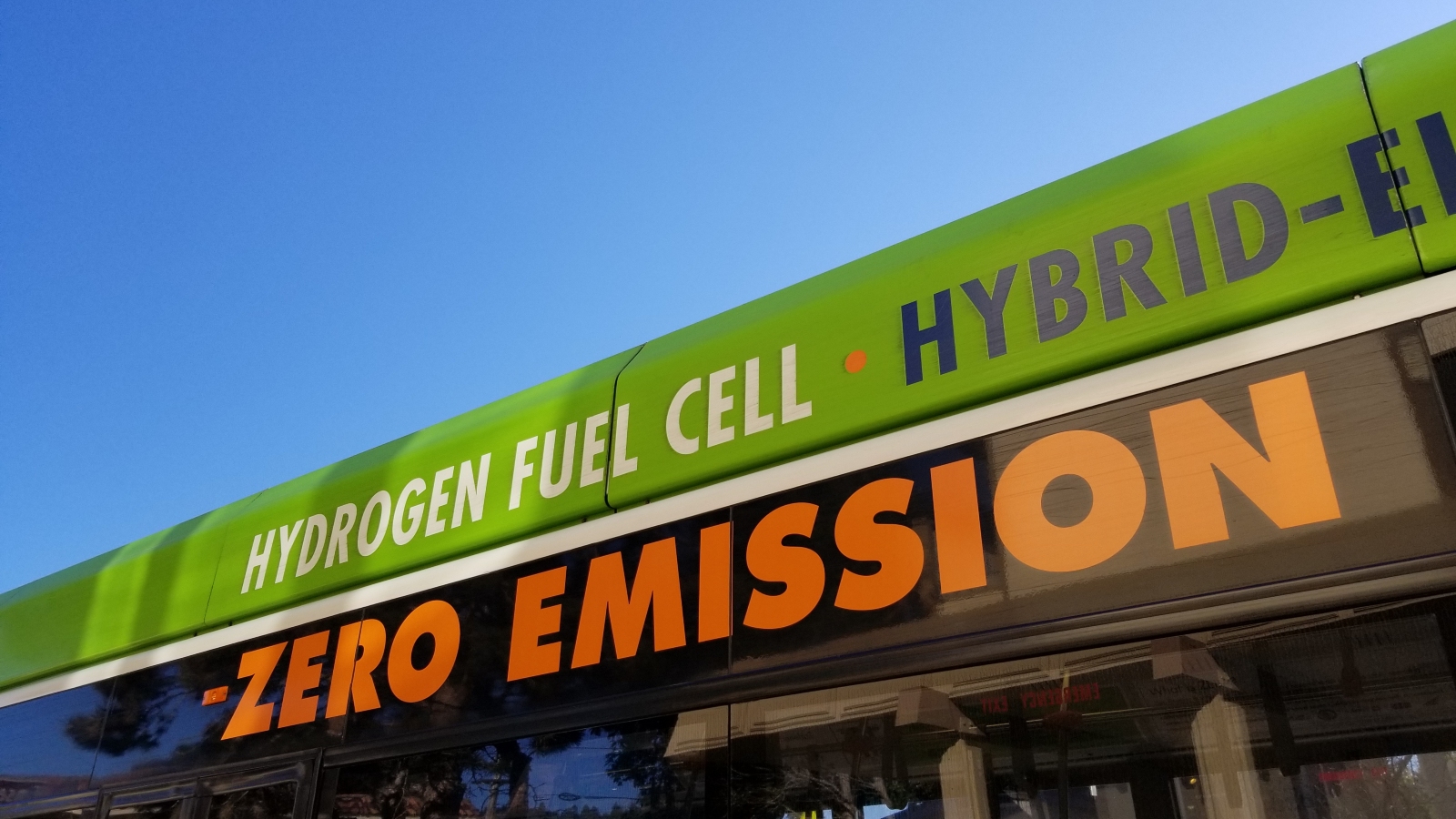

When burned, hydrogen releases water and heat — and zero carbon emissions — which makes it a clean source of energy that could reduce our reliance on fossil fuels. But because it’s generally hard to access natural hydrogen that comes from the Earth, industries have to produce it — hydrogen powers fuel cells for vehicles and is also a key ingredient in fertilizer. More of it could decarbonize sectors where electrification is difficult, like the shipping industry. But using industrial processes to produce hydrogen takes a lot of energy, usually requiring fossil fuels.

That’s why clean energy experts are excited about potential underground sources. Even though accessing the Earth’s hydrogen would require drilling, it would still use significantly less energy than producing hydrogen from scratch, according to Todd Allen, co-director of MI Hydrogen, a research institute at the University of Michigan.

“You may have some local energy used to run the drill, but the amount of zero-carbon energy you could get if there’s a lot of geologic hydrogen I think is a bigger advantage,” Allen said.

How likely are we to actually use geologic hydrogen as a power source?

More research is needed to figure out exactly where to drill for it and whether it’s feasible to actually extract it.

“OK, you find it, is there enough of it to be useful? Is it concentrated enough to be useful? Do you have to drill a hole 20 kilometers in the Earth to extract it?” Schrenk at MSU said. “We need the data about where it is to identify whether there are practical solutions to extract it.”

And if large amounts of hydrogen are found, building up infrastructure like pipelines or processing plants would be expensive and time-consuming.

So what does the governor’s executive directive do?

Current regulations around drilling “were all written assuming you’re drilling for something else, say, natural gas,” Allen said.

Governor Whitmer’s executive order will require state agencies to look at those existing laws and ask if anything needs to change for hydrogen drilling, Allen said. Reports from state agencies like the Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy and the Public Service Commission will be filed by April.

It’s still “too soon to tell” how big of an industry geologic hydrogen could be, Allen said. “You’re sort of right there at the beginning of the story. And there’s some opportunities for people to sort of nudge that story in a good direction.”