The spotlight

Eating a plant-based diet is one of the highest-impact actions a person can take to reduce their personal contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. A broader cultural shift toward plants in some of the meat-eatingest countries could lead to more efficient land use, less strain on water systems, and reductions in methane, the potent greenhouse gas that cows famously belch. Still, that’s easier said than done. On the individual level, people might have all sorts of reasons for clinging to animal products — including the concern that cutting them out will lead to nutritional deficiencies.

But one group of people is challenging the idea that a plant-based diet can’t be perfectly sufficient: the swole vegans of powerlifting, strength athletics, and personal training circles. My colleague Joseph Winters wrote a feature last week exploring the stories of some of these stereotype-smashing athletes.

While it’s difficult to put definitive numbers on the growth of veganism, Winters said, proxies indicate that the diet is gaining popularity generally — the plant-based meat market has grown hugely over the past few years, as has the prevalence of vegan restaurants and signups for “Veganuary” challenges (going vegan for the month of January).

“It’s definitely more normalized,” Winters said, adding that he had a lot of fun finding media coverage of vegan athletes from decades past. A 1974 Time magazine article that he cited in the piece exemplified the scrutiny that vegan and vegetarian athletes have often received; in describing the performance of NBA player Bill Walton, the article noted, “The vegetarian tiger played as if he had dined on red meat all week.”

“I think it’d be really weird if outlets covered vegan athletes like that nowadays,” Winters said. “Enough athletes have proven that you can cut out animal foods from your diet and still perform at a high level.”

In fact, one of the nutritionists he spoke to said that intense athletes are of the least concern when it comes to switching to a vegan diet. Because they’re already hyper conscious of protein and micronutrients like iron and B12, they should have little issue getting those things from plants instead of animal products. By contrast, “regular Joe” vegans might be at risk of deficiencies if they aren’t accounting for the protein and micronutrients lost by cutting out meat, dairy, and eggs. But another medical source Winters quoted said that most people don’t need to worry about hitting their daily protein requirement, as long as they’re eating a diverse diet without too many processed foods — whether those foods come from plants or critters.

“Personally, I think that Americans’ obsession with protein is misplaced, and I was very worried that I was going to be feeding that with this article,” Winters said. What Americans are more likely to lack is fiber — and eating more plants could help with that. (In fact, although this detail didn’t make it into the final piece, one of the vegan athletes Winters spoke to eats banana and orange slices with the peels still on, for an extra dose of fiber and micronutrients.)

By and large, the athletes Winters spoke to didn’t choose this diet to maximize their physical fitness — although many of them are performing at the top of their chosen fields. “They’re vegan mostly for concern about animals and the environment,” he said. “They also have this other part of their identity that’s focused on being an athlete, and they want to show that they don’t have to give up that part of themselves. They can have both at the same time.”

Vegan strength trainers are just one tiny niche of the population, but, Winters said, they’re contributing to a shift in what people imagine veganism to look like. It’s something he also thinks about personally, as a vegan marathon runner and biker.

“As a skinny man, I often worry that people think, ‘Oh, that’s what happens to you if you go vegan,’” he joked. “But then, I feel like I have good race times, which I can pull out when people doubt my athletic abilities — and say, ‘Look, you can still run somewhat fast on a vegan diet.’” (Let the record show that his half marathon time is 73 minutes — far faster than somewhat.)

We’ve excerpted Winters’ piece on swole vegans below. Check out the full story on the Grist site.

— Claire Elise Thompson

![]()

Meet the jacked vegan strength athletes defying stereotypes (Excerpt)

Over the past two years, Gigi Balsamico has won first place at more than a dozen strongman competitions in the eastern United States: Maidens of Might, Rebel Queen, War of the North, Third Monkey Throwdown. These events typically involve six to eight weight-lifting challenges on which competitors are scored based on criteria like the amount of weight they can handle and how many reps they can do.

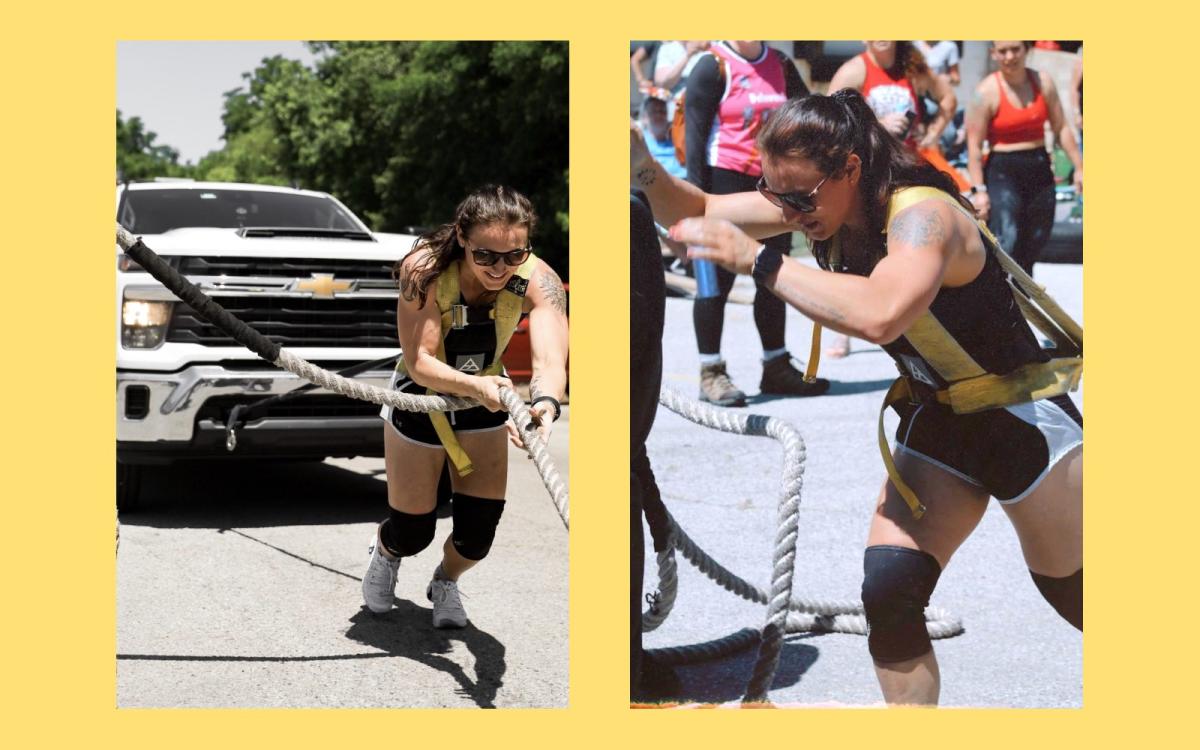

Last month, Balsamico came out at the top of her weight class at Delaware’s Baddest. There, she hoisted four 100- to 150-pound sandbags onto her shoulders after completing six reps of a 315-pound dead lift. As the pièce de résistance, she harnessed herself to a Chevy Silverado — which itself was attached to a food truck trailer — and dragged it 40 feet in 40 seconds.

Balsamico is also a vegan of 11 years. It’s an identity she’s vocal about, out of a desire to push back on the notion that you need to eat meat to be strong. When she was a vegan-curious teenager, it gnawed at her that giving up animal products could mean sacrificing sports.

“I thought I was going to shrivel away to nothing,” Balsamico told Grist. Her Italian, sports-loving family had always eaten meat and dairy. “That’s what was always said to me, that you would basically get so skinny and die.”

But Balsamico’s love for animals compelled her to question these concerns. As a child, tending to neglected horses at a family friend’s farm prompted her to wonder why people didn’t see all animals as beautiful, each with its own unique personality. Horses, cows, sheep, dogs: “It was so apparent to me that there was no difference,” she said.

Meanwhile, veganism was at the beginning of a surge in popularity — concerns over the cruel conditions of factory farming, as well as the impacts of animal agriculture on the climate and environment, were helping to bring the marginalized diet closer to the mainstream. Although estimates vary, peer-reviewed research suggests that the chickens, cows, pigs, and other animals humans raise for meat and dairy contribute up to 20 percent of the planet’s overall greenhouse gas emissions.

Balsamico cut out all animal products from her diet at the age of 14, justifying the decision to her parents in a “39-minute PowerPoint” on the health benefits of plant-based eating. The weight lifting came a couple of years later, mostly out of curiosity: “I just wanted to see if I could do it,” she said. And she could — in 2022, she began winning first place for her age and weight class in every strongman competition she entered, racking up a streak of victories that she has yet to break.

“I haven’t had meat in 11 years of my life, and I can pick up 700 pounds on my back,” she told Grist. Balsamico now coaches other aspiring athletes at a gym in Pittsburgh, and is affiliated with an international team of vegan strength competitors called PlantBuilt.

Balsamico and her teammates are just a few of the many plant-based athletes who are using their “swole” bodies and competition results for social change, showing on social media and through word of mouth that you don’t have sacrifice “gains” — slang for muscle mass gained through diet and exercise — in order to eat a diet that protects animals and the environment. One block of tofu at a time, they’re defying expectations about what’s possible without animal protein — and weathering unsolicited criticism from those who insist, against all evidence to the contrary, that “soy boys” are inherently weak.

— Joseph Winters

Read the full piece here to learn more about how endurance athletes, strength builders, and fitness coaches are championing a diet that’s lighter on the planet.

More exposure

A parting shot

Behold: Gigi Balsamico, one of the vegan strength athletes Winters interviewed, pulling a Chevy Silverado and food truck trailer as part of Delaware’s Baddest, a strength competition she competed in last month.