In early August, in the village of Utulei on the eastern shore of Tatuila, the largest of seven islands that make up American Samoa, more than two dozen local residents gathered in an auditorium. They were there to learn about a proposal to allow deep-sea mining across more than 18 million acres of their surrounding waters in the Pacific Ocean.

President Donald Trump had issued an executive order to jump-start the nascent deep-sea mining industry three months earlier. Within weeks, the U.S. Department of the Interior began asking for public input on leasing the seabed surrounding American Samoa, and the territorial government organized a series of meetings to help educate the public on what to expect.

During the meeting, Oliver Gunasekara, co-founder and chief executive officer of a mining company called Impossible Metals, appeared on Zoom from San Jose, California, to give a presentation about how his company’s proposal to mine the seafloor about 130 miles offshore would benefit the American Samoan community.

“We have committed to provide 1 percent of our profits from the American Samoa EEZ to the community of American Samoa,” said Gunasekara, using the acronym for Exclusive Economic Zone, which refers to the waters surrounding American Samoa up to 200 miles from shore. Gunasekara said his company expects to generate up to $1 billion of annual revenue from mining; 1 percent would translate into $10 million for American Samoa per year.

About half an hour later, a local woman stood and commented on Gunasekara’s proposal. “I think it’s an insult that it’s 1 percent,” she said. “This is our ocean.”

“Many millions of dollars a year is not an insubstantial amount of money,” Gunasekara replied. “There’s no legal requirement for us to do this. This is something that we have voluntarily done. To my knowledge, no other mining company has.”

To Sabrina Suluai-Mahuka, who leads American Samoa’s climate resilience office and helped organize the meeting, Gunasekara’s response did not go over well. Neither did references by other industry officials to how it is preferable to mine “remote” parts of the Pacific than on land.

“Our waters are not isolated,” Suluai-Mahuka told Grist. “We live here.”

A year ago, American Samoa’s then-governor issued a moratorium on deep-sea mining around the central Pacific archipelago. Yet when Trump issued his executive order on seabed mining in April, local leaders did not immediately reject it. Just a week earlier, the territory’s current governor, Pula Nikolao Pula, had publicly lauded Trump’s effort to open up Pacific conservation areas to commercial fishing, the islands’ leading industry.

But after discussing and researching the proposal, every major political leader in American Samoa came to agree: Their answer is no. “There is strong opposition to any exploration or extraction of minerals from the ocean floor in waters near American Samoa,” wrote Representative Amata Coleman Radewagen, American Samoa’s only U.S. congressional representative, in her official comments to the Interior Department. She described how Samoan culture, known as fa’a samoa, includes the story of a mother and a daughter who transformed into a turtle and a shark and swam to Tutuila.

“This is where the people stand, and I stand with the people — to preserve the shark and the turtle and fa’a samoa,” she said.

Yet whether or where the mining happens may not be up to the local Indigenous people. Unlike the independent country of Samoa, just a day’s sail away, American Samoa is a U.S. territory, subject to the whims of the American flag. Radewagen has a seat in the House of Representatives, but she is not allowed to vote, and U.S. territories have no voice at all in the U.S. Senate.

Residents of American Samoa, like residents of other U.S. territories, had no choice in whether Trump or Kamala Harris became president. Under international law, Indigenous peoples have the right to consent to projects on their lands, and in previous disputes with the federal government, American Samoa has pointed out that when it was established, the U.S. promised to respect the rights of its people. But while the Department of the Interior has elicited American Samoansʻ opinions on seabed mining, the agency’s current process could allow mining to proceed over the community’s objections.

Angelo Villagomez, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress specializing in Indigenous-led conservation, is among more than 2,000 current and former residents of U.S. territories who signed a petition opposing the mining proposal. He said the situation in American Samoa reflects a broader assault on public lands and waters by the Trump administration, and highlights the political disparity facing residents of U.S. territories.

“No place is safe under this administration,” Villagomez said. “They’re not just trying to drill for oil in the Gulf of Mexico and off the East Coast — they’re going to the farthest reaches of the American empire to look to extract natural resources,” he said, adding: “We should only be doing these things if the people who have to live with the outcomes are supportive of it.”

John Wong / AFP via Getty Images

Deep-sea mining is the process of removing minerals like manganese, cobalt, nickel, and copper from the bottom of the sea at depths greater than 650 feet (or 200 meters). In recent years, companies have spent millions of dollars investing in technology and testing it in the hopes that the fledgling industry will get the green light from national and international regulators to begin mining commercially. The problem, said Andrew Thaler, a Maryland-based deep sea ecologist and environmental consultant, is that less than half a percent of the deep-sea floor has been studied. Recently, scientists discovered a deep-sea coral reef almost as big as the Great Barrier Reef that lies perilously close to a seabed-mining test site from the 1970s. “They came within 20 kilometers of basically strip-mining the largest deep-sea coral reef on the planet 50 years before we even knew it existed,” Thaler said.

Hundreds of scientists have raised alarm about the industry’s potential to destroy sensitive habitats of animals that have evolved undisturbed for millions of years.

Gunasekara says his company is different. While other mining companies want to rip metals off of sea crusts or drill into hydrothermal vents to pull out metals, Gunasekara’s company is committed to only one type of extraction method: removing potato-sized globs of minerals, known as polymetallic nodules, from the ocean floor.

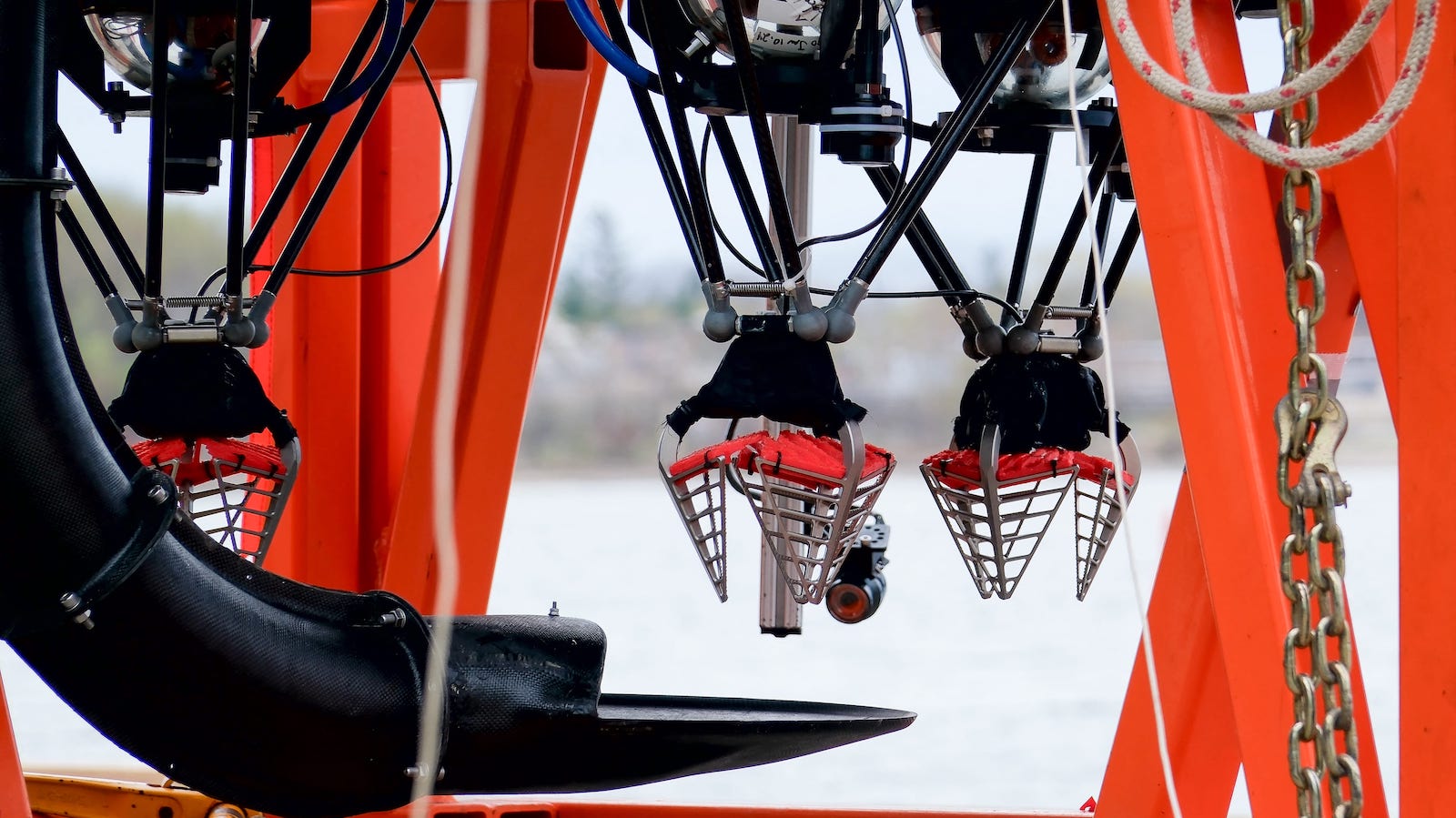

To do that, Impossible Metals invented robots that descend into the ocean and hover above the seabed. When the machines identify a polymetallic nodule, a robot arm reaches down and grabs it, similar to a claw machine grabbing a stuffed animal in an arcade. Gunasekara said the robots are smart enough to avoid living creatures, and he expects to program the machines to pick up 40 percent of the nodules they see, leaving most of the habitat behind undisturbed.

This robotic arm, part of the Eureka II, is designed to pick up polymetallic nodules from the ocean floor with minimal damage to surrounding habitat and creatures.

John Wong / AFP via Getty Images

Polymetallic nodules are bulbous lumps of rock rich in battery metals such as cobalt and nickel that can be found in huge swaths of the Pacific Ocean seabed. They’re formed over millions of years.

William West / AFP via Getty Images

That’s far different from the house-size tractors that other mining companies intend to drive over the seafloor that would necessarily crush the creatures beneath them. In addition to pursuing his own mining operations, Gunasekara wants Impossible Metals’ technology to be adopted by other companies.

“We would like our tech to be the preferred moving forward because it’s much less environmentally invasive, no sediment plumes, no biodiversity loss,” Gunasekara told Grist. “I want to be crystal clear: I’m not saying we’ll have zero impact; I’m just saying we will have by far the lowest impact of any form of mining anywhere on the planet.”

Gunasekara said Impossible Metals’ robots would also avoid releasing plumes of sediment that other mining companies expect to release when lifting minerals up to the surface. Avoiding or minimizing that plume is important because scientists fear that mineral-rich sediment plumes could contaminate fisheries. Such pollution could be disastrous for American Samoa, where tuna makes up 99.5 percent of the territory’s exports.

Jeffrey Drazen, an oceanographer at the University of Hawaiʻi who has studied the environmental effects of deep-sea mining, said he likes the idea of Gunasekara’s technology, but has no idea if it’s going to work. “It’s hard to evaluate any of these claims because it needs to be trialed,” Drazen said.

There aren’t any peer-reviewed studies validating Gunasekara’s claims, and a federal environmental analysis hasn’t yet been completed. The company has tested its technology off the coast of Florida, but it still needs more analysis. “If it all works, then it will reduce environmental risk,” Drazen said of Gunasekara’s technology. At the same time, “It’s still mining. It’s still removing a substrate from the bottom of the ocean that takes millions of years to form and is habitat for the animals who live there.”

Gunasekara thinks that the environmental cost is worth it, because the minerals that are contained in the polymetallic nodules could help create batteries for electric vehicles and other green technologies, reducing energy dependency on fossil fuels.

“We all want to protect the ocean. But the biggest threat to the ocean, especially the deep ocean, is climate change,” Gunasekara said. “And so the question is, Where do we get the metal from to displace fossil fuels?”

Gunasekara is far from the only entrepreneur who sees opportunity in the demand for minerals and potential for profit. Companies have for years been building support among other Pacific islands like the Cook Islands, funding numerous local causes like medical equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic and the construction of traditional canoes in the hopes that they’ll be able to tap into what’s been called a “$20 trillion opportunity.” Those efforts seem to be paying off: The Cook Islands’ prime minister has been supportive of seabed mining, and just a few weeks ago, the country signed a new agreement with the Trump administration for seabed mining exploration.

American Samoa hasn’t seen that same level of community investment; Gunasekara from Impossible Metals hasn’t yet visited. “We’re not a massive company, and so we have not been on the ground, although we’ve had multiple calls with the governor’s office and with other people,” Gunasekara said. Currently, the Delaware-based startup employs 15 full-time workers.

Part of the reason mining companies are not flocking to Tutuila is that, ultimately, Gunasekara expects the decision on mining leases will be made 7,000 miles away in Washington, D.C. “These waters are not within the jurisdiction of American Samoa,” Gunasekara told Grist. “They may not like this, but under federal law, 3 miles off the coast belong to the territory or the state; from 3 miles to 200 belong to the federal government, and it is purely their jurisdiction.”

That’s also why Gunasekara is not discouraged by local opposition to his plan. He thinks there’s a less than 1 percent chance the Trump administration will stop the process given how enthusiastically the president has embraced mining. “They are required to be consulted, but it’s not their decision,” he said of local officials. He noted the territory also doesn’t have the right to any federal lease revenue for seabed mining the same way states like Texas and Louisiana get a cut of offshore oil and gas lease revenue, although Gunasekara said he’s in favor of changing that.

The Department of the Interior is still at the beginning of the process of issuing any seabed mining leases. The agency plans to review the public comments, identify specific areas for mining, and conduct an environmental assessment before making any leases available.

Suluai-Mahuka, the climate change resilience director in American Samoa, said the community’s lack of decision-making power comes up frequently in conversations about potential mining. “It’s within our EEZ, but it’s not within our call or our voice to say whether or not we can auction off our seabed,” she said.

“But at the end of the day,” she continued, “the question is, Whose livelihoods are going to be affected? It’s American Samoa. Whose economy might be affected with our reliance on the fishing industry? American Samoa. And whose historical ties and identities are tied to these waters? It’s American Samoa. It would make sense for our consent to be given if there was deep-sea mining,” she said. “And if the process continues, and our consent is not given, that’s very telling.”