Artists can be effective boundary spanners, interacting between scientists, natural resource managers, and residents, bringing creative problem solving approaches to this nexus.

about the writer

Chris Fremantle

Chris is a researcher and producer working across environment and health. His research focuses on the pioneering ecological artists Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison who he also worked with. He is currently exploring artists’ projects with trees, woods and forests. Chris is a Research Associate with TNoC’s naturePLACE supporting evaluation approaches.

about the writer

Stabbers McGuillicutty

Stabbers McGuillicutty is passionate about cities, ecosystems, and the people who care for them. She is a human geographer whose work seeks to understand how and why people take care of their environments — particularly amplifying less-told stories about neighborhood leaders, cultural knowledge keepers, stewards, and activists. She loves transdisciplinary collaboration that gets beyond silos, convening scientists, artists, and stewards to explore creative approaches to complex challenges related to sustainability, resilience, and justice.

about the writer

Erika Svendsen

Dr. Erika Svendsen is a social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station and is based in New York City. Erika studies environmental stewardship and issues related to hybrid governance, collective resilience and human well-being.

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

about the writer

Michelle Johnson

Michelle Johnson is a research ecologist with the USDA Forest Service at the NYC Urban Field Station.

about the writer

Cara Broadley

Dr Cara Broadley is a design researcher exploring how participatory, creative, and visual methods can help make complexity legible within democratic practice, public sector innovation, and governance. She is a Research Fellow in the School of Innovation and Technology at The Glasgow School of Art, working across parliamentary scrutiny, community empowerment, net-zero transitions, and public policy.

In the context of the increased complexity of socio-ecological challenges and the growing involvement of arts and culture in climate action (increasingly framed as culture-based climate action), we need to be able to analyse and understand the dynamics of transdisciplinary work involving artists. Reports of artists’ collaborations with natural resource managers and researchers tend to take the form of case studies or vignettes, substantiated by descriptions of activities and artworks. The best of these capture what “made a difference” and what the benefits were to those involved. Patterns, such as the importance of transdisciplinary approaches, can be highlighted by grouping case studies. However, the specificity of the interactions and outcomes that make for a great case study can also make it difficult to understand how to apply the lessons elsewhere.

It is because of this challenge that Theories of Change have become a tool for programmes, whether in international development, health, or environment, to articulate underlying logics. Theories of Change draw out assumptions and provide a means to interrogate how an action might be linked to a particular outcome, which in turn serves the overarching mission.

The NaturePLACE Collaborative Arts Program team, a collaboration between the USDA Forest Service and non-profit The Nature of Cities, along with state and municipal partners, identified that a Theory of Change could be a useful asset. Developing a Theory of Change would support engaging with potential partners and funders, as well as underpin evaluation. Over the past 18 months, the team has workshopped internally and engaged with agency teams, alumni, and current participating artists.

The NaturePLACE Theory of Change

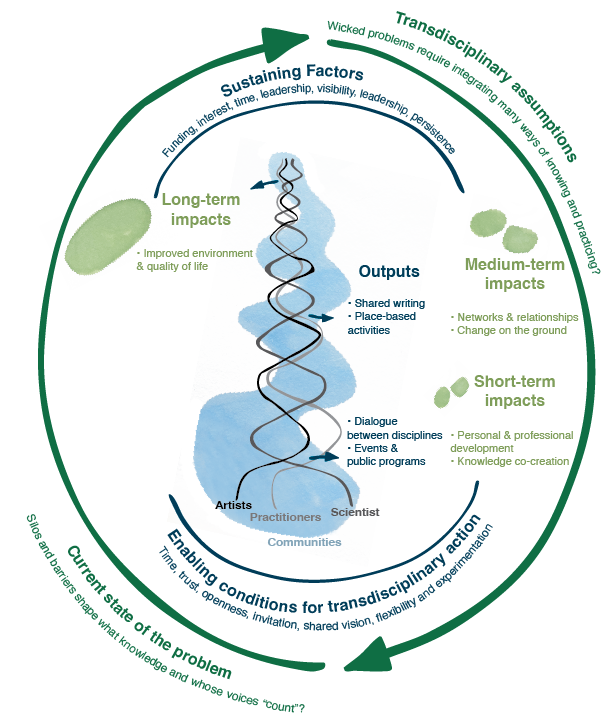

The process of developing a Theory of Change enabled the team to identify the main outputs and impacts (indicated in the diagram as short, medium, and long term) or “leverage points” of the program, as:

- The artists, researchers, and natural resource managers involved in the program report on personal and professional development resulting from interacting in cohorts.[1]

- New knowledge and understanding are co-created between artists, scientists, and natural resource managers, resulting in outputs including presentations, public programs, blogs, papers, and artworks.

- The Program mobilises new activity and practices in specific places through facilitating collaborations between artists, scientists, and natural resource managers.

It also became apparent through this process that there was a fourth ‘leverage point’ which is the potential of the program to leverage cultural changes and institutional shifts to effectively address disciplinary silos and organisational barriers at the structural level (indicated in the diagram by “Sustaining factors” and “Enabling conditions for transdisciplinary action”). Cultural change and institutional shifts are achieved through the “feedback” from individuals’ development, co-created new knowledge, and the mobilization of on-the-ground activity.

Another key factor that emerged was the importance of time (indicated in the diagram by the triple helix), literally in the sense of the year-long duration of the residency as well as continued relationships during alumni status, but also in terms of time to find the outcomes and products that all participants value, time to learn and grow, time to do creative problem solving.

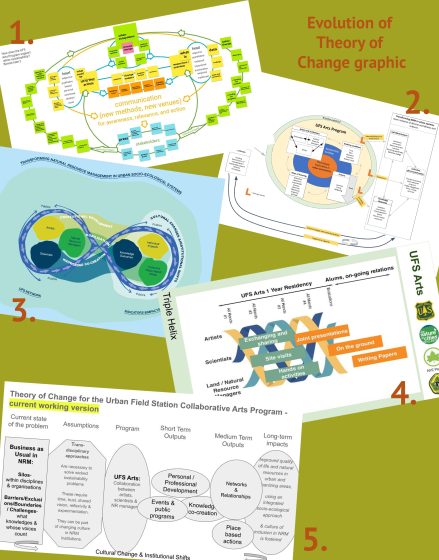

To develop the Theory of Change, the team started with a Fuzzy Cognitive Modelling exercise led by Forest Service Interdisciplinary Scientist Michelle Johnson. This exercise enabled all the core team members to co-create a visualisation of the dynamics of the Program. This generated two key aspects: firstly, that the problem was complex and not understood as linear by the team, and secondly, that there were “leverage points” in the system. By leverage points, we mean activities that in themselves might involve small changes but can have wider impacts. This resulted in a graphic that focused on complexity and helped highlight the assumptions.

Visual development is an important aspect of this work because one of the defining characteristics of Theories of Change is that they have a graphic representation. The usefulness of the Theory of Change is dependent on the visualisation. Visualisations are a useful tool for explaining complex programs and processes that drive change. Based on searches, the form of graphics in Theories of Change has been subject to no or limited scrutiny from a design research perspective. The usefulness of visual metaphors such as linear models, circular models, infinity loops, and triple helix devices has not been subject to consideration. The team brought Dr Cara Broadley of the Glasgow School of Art onto the project to co-develop the visual diagram above through an iterative process.

What is NaturePLACE?

The NaturePLACE Collaborative Arts Program) has been involving artists in the USDA Forest Service’s Urban Field Station Network (UFS Network) since 2016, initially in New York City and later in other Field Stations (e.g., Baltimore, Springfield, Denver, Puerto Rico) as well as with other sites of long-term ecological research and practice (e.g., Honolulu, Hawaii; Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic).

The NaturePLACE program offers a one-year affiliation with agency partners in a location and a stipend in exchange for delivering a public program (an event, a workshop, a talk, a guided tour, a training session). Artists are able to use the Field Station and partner resources, participate in events such as regular Stewardship Salons, connect with scientists and natural resource managers, and access datasets and field sites. Projects can be on the table from the start or emerge during the year ― they often require additional resources (funding, materials, expertise, networks) beyond the stipend, and usually relationships and projects extend beyond the first year of engagement. It is useful to understand the program as the initial phase, enabling an artist to develop an idea or to engage with natural resources management and research as a “creative problem-solver”, finding the important issue on which they can collaborate. The NaturePLACE website documents the program, links to stories in various media, including with partner organisation The Nature of Cities. Papers focusing on case studies and analysing evaluations are published or under review.

Why a Theory of Change?

Generally speaking, Theories of Change are articulations of interventions. The interventions are aimed at addressing issues with “business as usual” (indicated in the diagram by “current state of the problem”). Natural resource management is faced with wicked problems ― problems with no single agreed definition, no single solution or point where it is solved, and multiple stakeholders with differing perspectives. One of the key challenges in natural resource management are silos, whether those are the silos of organisations focused on their specific missions and objectives, or the silos of disciplines. All of these create fragmentation where places and people are framed in terms of specific issues and methods. If silos are one challenge, then the other is barriers, resulting in some people being involved in decision-making and others less so; some people’s expertise, worldview, or way of knowing counts for more than others. Different perspectives don’t get heard. It raises issues with procedural and recognitional justice. Consistent feedback from researchers and natural resource managers highlights the need for better, two-way engagement.

The UFS Network is in itself intended to address these challenges. Its mission is to “improve quality of life and natural resources in urban and urbanizing areas, using an integrated socio-ecological approach”. The NaturePLACE Program contributes to this mission by facilitating transdisciplinary collaboration between artists, scientists, and natural resource managers. NaturePLACE curates events and public programs that explore ideas emerging from these collaborations with the overall aim of building understanding and engagement in social-ecological systems through the arts. We have in this process the bones of a Theory of Change.

Theories of Change are frequently developed starting with the mission, in this case, the UFS Network’s mission to improve quality of life through integrated socio-ecological approaches. The challenge with “business as usual”, in this case, siloes and barriers, provides the context for the intervention. The program activities and the expected outcomes should all be clearly directed to the overall mission. The NaturePLACE activities of “facilitating collaborations between artists, scientists and natural resource managers” and “curating events and public programs” supports the mission of the UFS Network (the three strands of the triple helix embedded in the wider field become increasingly tightly engaged as time passes, indicating that the collaboration can strengthen over time, generating different outputs and impacts).

Theories of Change have a second key function ― to articulate assumptions (indicated in the diagram by “Transdisciplinary assumptions”). There are two interlinked underpinning assumptions to the NaturePLACE Program. Firstly, that artists can be stimuli to transdisciplinarity, and secondly, that transdisciplinarity is the best way to develop “integrated socio-ecological approaches”. The assumptions in a ToC speak to the challenges of “business as usual”.

Why Artists?

The first assumption is that artists are specifically relevant to natural resource management and the wicked problems it faces. Artists focusing on social and ecological issues tend to take co-creative approaches, bringing different ways of working together. Artists might also approach circumstances without a hypothesis, i.e., without a preconceived idea of what might be useful. Even artists who might start with a project may actually be using this as a way of engaging people, rather than a proposed solution. The project may be “diagnostic” rather than “the answer”. What all these points add up to is that artists can be effective boundary spanners, interacting between scientists, natural resource managers, and inhabitants, bringing creative problem solving approaches to this nexus.

Natural resource management, often working on intergenerational timescales, needs both consistency (what “business as usual” does deliver) and also to involve people in different ways and at different stages, to value different ways of knowing, and to be open to emergence. Artists are perhaps a proxy for this ― they come into natural resource management in different ways and at different points in long-term processes. Artists bring different ways of knowing, but also the ability to imagine and shape value and meaning. Artists imagine and experiment, generating novel ways of making sense.

Why Transdisciplinarity?

Transdisciplinarity is one of a cluster of terms that address the way knowledge is produced. Disciplines are not the only ways that knowledge is produced, but they are a focus for the development of knowledge across the natural and social sciences, medicine, computing, as well as humanities. However, disciplines can also become silos. The proliferation of terms (multi-, inter-, trans-, cross-disciplinary ) is a reflection of the need to work in a range of different ways, not solely within disciplines. To understand the role of transdisciplinary approaches, it is useful to relate them to other varieties:

- disciplinary approaches ― disciplines within their own methods, forms of verification, and outlets (and intra-disciplinary refers to people of the same discipline collaborating within their discipline);

- multi-disciplinary approaches ― which are groupings of disciplines working together, such as are found in healthcare, where disciplines maintain their methods and frameworks;

- interdisciplinary approaches ― disciplines sharing, exchanging, and hybridising ― where methods and frameworks are integrated. This sometimes ends up with new disciplines such as biochemistry or nuclear medicine, but does require “compatibility”, shared assumptions about verifiability;

- transdisciplinary approaches are approaches that put complex problems and social relevance foremost ― usually involve varied ways of knowing, some of which involve disciplinary knowledge and some of which might be vernacular or place-based. These can have incommensurable forms of verification, addressing different levels of reality, such as the scientific and the spiritual. Transdisciplinary work usually involves people who are living with the problem collaborating with social and natural sciences, as well as arts and humanities.

Transdisciplinary approaches are therefore not better than any of the others, but they are suited to complex socio-ecological contexts where residents have knowledge and ways of life embedded in places, stakeholders have differing agendas, and problems don’t have single solutions. Transdisciplinary approaches do assume epistemological equity ― starting from an assumption that everyone’s ways of knowing are equally valid, but also need to come into relationships with other ways of knowing, with all the attendant and inevitable negotiations. Disciplinary expertise needs to recognise and value organisational expertise, and both need to acknowledge the expertise of Indigenous and other place-based forms of knowledge. Here, the challenge of procedural justice comes in ― transdisciplinary approaches need to pay attention to power relations and enact equity.

Why do Transdisciplinary projects go wrong?

David Maddox, founder of The Nature of Cities, based on years of experience as a scientist, musician, and theatre-maker, has used a Theory of Change approach to ask some key questions focused on the difference between intra-disciplinary collaboration (i.e., collaboration between people in the same discipline) and transdisciplinary collaboration. “What are the relative strengths of different pathways to addressing wicked problems?” David’s thinking maps traditional and co-creative approaches, taking account of routes to mainstreaming as well as direct problem-solving. “Can engagement in transdisciplinary projects feed back into intra-disciplinary work?” Or as he puts it more directly, “Are you different when you go back to your desk?”

There is a non-exhaustive list of characteristics of what might make a transdisciplinary project more likely to succeed:

- Trust

- Shared vision

- Varied methods

- Transdisciplinarity from start to finish

- Mixed working groups

- Groups small enough to think radically

- Enough time to learn and grow not just be tactical

- Outcomes and products that all participants value

- Integrated storytelling

- Buy-in from leadership

David Maddox’s Theory of Change is more tactical and informs NaturePLACE’s Theory of Change. The characteristics needed for success are critical and have been carried over into the NaturePLACE effort.

Conclusion

A Theory of Change is a way of understanding an intervention, but the circumstances will change, and the process will need to adapt. A Theory of Change doesn’t solve a problem, but it can help to understand what sorts of activities are useful. On one level, a Theory of Change is relative to an intervention and might be specific to a team at a point in time.

The potential wider relevance becomes more apparent if NaturePLACE is seen as one of a type of program aiming at supporting the wider integration of artists and designers into long-term ecological research processes. The Theory of Change clarifies that NaturePLACE is focused on personal/professional development and building capacities to collaborate across artists, natural resource managers, and researchers. It provides a context for co-creation of knowledge manifest in exhibitions, essays, and articles as well as artworks. And it supports mobilisation of specific initiatives “on the ground”.

Any Theory of Change is, by definition, conceptual and aspirational. It needs to be explored, questioned, proved and improved, and the challenge of silos remains because they are not in themselves bad. Silos, whether disciplines or organizations, are important because they offer consistency. If a problem is “wicked” (has no single definition, solution, or point where it is solved), yet our approach needs to still be driven by a mission or vision, then our approach needs to have multiple points of entry, support different methods of working, and be open to emerging outcomes. The NaturePLACE Program builds the network of competence to collaborate and introduce imagination and creative problem solving. Exploring how this Theory of Change might relate to other long-term ecological research programs that work with artists is the next step we envisage.

Chris Fremantle, Stabbers McGillicutty, Julie Hernandez, Erika Svendsen, David Maddox, Michelle Johnson, Cara Broadley

Glasgow, New York, Amsterdam, New York, New York, New York, Glasgow

Acknowledgements:

The authors are very grateful to the artists and agency partners for their engagement and input, especially Bonnie Ralston. Chris Fremantle is very grateful to his wife Gill Fremantle for her feedback.

[1] These are captured through annual program evaluations, which use a “knowledge exchange” focus.