about the writer

Praneeta Mudaliar

Praneeta Mudaliar is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Natural Resources Policy and Stewardship at the University of Toronto Mississauga. Her interdisciplinary social scientific research and teaching spans the commons, collective action, climate justice, climate policy, and decolonizing conservation.

about the writer

Tasmia Jamil

Tasmia is a Master’s student in Human Geography at the University of Toronto. Her research focuses on environmental justice and environmental non-governmental organizations based in Ontario.

For students like Tasmia—who have struggled to share their environmental experiences or worldviews—this work will support underrepresented youth by connecting them with organizations that align with their vision for environmental justice, thus revealing paths to belonging and purpose.

In Canada and elsewhere, environmental organizations often explain the low participation of racialized or marginalized people by leaning on a deficit narrative: the idea that these communities lack the knowledge, interest, or capacity to engage in environmental action [1]. However, exclusion is not disinterest; it is a result of structural and institutional barriers and occurs when organizations may narrowly frame “environmentalism” by focusing on individual behaviors such as recycling, consumption, or carbon footprints, overlooking the lived realities, cultural worldviews, and priorities of others.

For the first author of this essay, Tasmia Jamil, a student pursuing her Masters in Geography at the University of Toronto Mississauga, this exclusion was personal. Tasmia did not “lack interest” in the environment; instead, she encountered conversations in environmental clubs at school that were disconnected from her worldview and cultural knowledge. Growing up as a racialized immigrant-settler and Muslim woman in a majority-white suburb of the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) in Ontario, Canada, her summers were spent at Qur’an class and playing in local parks. On the other hand, her classmates visited serene lakeside cottages or had camping adventures at the Muskoka campsites in Northern Ontario, renowned for its natural beauty. As first-generation immigrants, her family lacked resources or time for a road trip to an affordable cottage. Even at the Eco-club at school, discussions largely revolved around recycling, leaving no room for her to share her Islamic understanding of stewardship. In other words, Tasmia did not feel seen in these environmental groups. Later, as an aspiring activist, these experiences made her hesitant to join environmental organizations without knowing their values or commitment to marginalized communities.

From exclusion to mapping change

Her experience reflects a broader problem: organizations rarely make their commitments to justice visible enough to inspire marginalized people to join their organization, especially when marginalized people are unsure if they will be welcomed or erased in conversations around environmental action. For instance, global climate movements such as Fridays for Future (FFF) and Extinction Rebellion (XR) faced criticism from activists in the Global South, who argued that the movement centered white, European experiences and ignored the experiences of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities [2]. Tasmia’s experience, therefore, led us to ask: what if there were an accessible way for people to identify environmental organizations whose missions align with environmental justice values?

From this question, the idea for our current project emerged: creating an Ontario-wide database and interactive map of environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) in Ontario that depicts the dimensions of environmental justice they address.

Why Environmental Justice?

We ground this work in environmental justice because it offers a framework for understanding exclusion as a structural problem. Mainstream environmentalism can become technocratic and apolitical, while ignoring the social and historical contexts that shape participation and knowledge. By contrast, environmental justice aims to dismantle inequities in the distribution of environmental harms and benefits (distributive justice) [3], ensure meaningful participation and inclusive decision-making (procedural justice) [4], and recognize the diverse worldviews and lived experiences of underrepresented, marginalized, and vulnerable communities (recognitional justice) [3].

In response to the Black Lives Matter movement and the COVID-19 pandemic, many ENGOs in Canada pledged to advance environmental justice [5]. Yet, without clear, public articulation of what justice means in their work, these commitments can remain vague or symbolic. Our database aims to fill this gap by making visible how ENGOs in Ontario incorporate different justice dimensions into their missions and practices, providing both communities and organizations with a clearer picture of the environmental justice landscape.

Database challenges and insights

The main challenge in creating the database was a deceptively simple question: what is an ENGO? Over time, we defined ENGOs as not-for-profit interest groups, including lobby groups for political advocacy, with paid staff, and volunteers, and a focus on environmental issues [6].

We found that some organizations explicitly state that they are an NGO; others use vague language, calling themselves associations, alliances, coalitions, councils or social enterprises, with varying focus on environmental issues. For example, not-for-profit interest groups, like the Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario – EFAO, support knowledge-sharing and resilient ecological farming to increase biodiversity and mitigate climate change. However, for-profit interest groups like the Forest Products Association of Canada – FPAC, represent environmental issues, but prioritize monetary profit for their members. Although both are ENGOs, we classified the EFAO as an ENGO since it is not-for-profit interest group, while FPAC is a for-profit interest group.

ENGOs Environmental Justice dimensions

We have also been identifying preliminary trends and patterns of environmental justice in the mission statements of ENGOs. Firstly, out of 691 ENGOs, most organizations (44%) are based in two major cities in Ontario: Ottawa, the capital of Canada, hosts 107 organizations (15%), and Toronto, the capital of Ontario, hosts 198 organizations (29%). Toronto and Ottawa are urban hubs of financial, political, and institutional power, so ENGOs might naturally gravitate toward these places to secure funding and influence policy. At the same time, the rest of Ontario has fewer ENGOs, raising the question of whether environmental issues in smaller cities, remote areas, or regions most impacted by climate change (e.g., northern territories, coastal zones) are adequately represented in policy and advocacy.

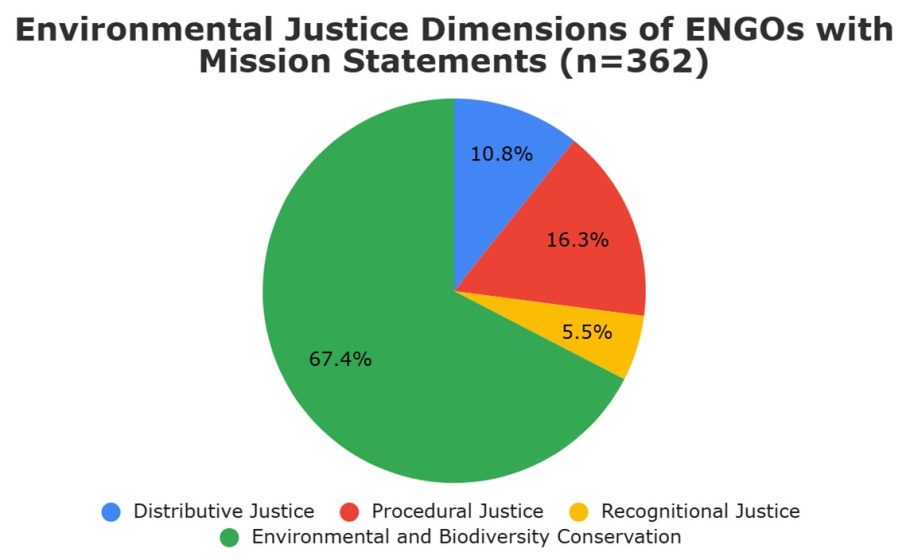

Next, out of 691 ENGOs in the database, we can report preliminary findings on 550 ENGOs since this is a work-in-progress. Out of these 550 ENGOs, only 362 ENGOs have mission statements (66%). Out of these 362 ENGOs, only 39 mission statements of the ENGOs (10.8%) fall under distributive justice since they seek to improve access to the environment, knowledge, and legal resources. ENGOs that seek to create spaces for public participation for marginalized groups are coded as procedural justice (59 mission statements, 16.3%). For instance, political advocacy organizations like Ecojustice, in Toronto, and Legal Advocates for Nature’s Defence ― LAND, in North Bay, provide mechanisms for communities impacted by environmental and climate injustices to participate in judicial processes.

With regards to recognitional justice, we found only 20 ENGOs with mission statements (5.5%). For instance, Green Ummah and the Black Environmental Initiative, based in the GTA, promote environmental equity and provide space for underrepresented Muslim, Black, and Brown communities. Both organizations were founded in 2019, and it’s worth exploring whether 2019 marked a turning point for ENGOs to advance recognitional justice.

Thus, in total, only 32.6% of the ENGOs in our database focus on some aspect of environmental justice, while the rest 67.4% engage in environmental and biodiversity conservation, without explicit engagement with environmental justice. This imbalance highlights a critical gap: despite growing recognition that environmental challenges are inseparable from issues of equity and inclusion, most ENGOs in our database reproduce a narrow, conservation-focused agenda. Explicitly articulating a commitment to environmental justice in mission statements is important because it signals organizational priorities, guides decision-making, and communicates accountability to marginalized communities and funders.

At the same time, mission statements tell us only a part of the story. For instance, well-known ENGOs, such as the Sierra Club Canada Foundation, committed to justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion programs in 2019, but do not explicitly refer to these concepts in their mission statement. Thus, there is more to be gleaned from examining other communication materials of ENGOs, such as strategic plans, annual reports, newsletters, and triangulating this data with interviews or surveys of ENGO members. We plan to pursue this in the next phase of our research.

Improving accessibility of ENGOs to interested citizens

In addition to analyzing the environmental justice dimensions of the mission statements of ENGOs, we’re also creating an online map of the location of the ENGOs along with the EJ dimensions on ArcGIS to serve as a public resource for communities, researchers, and organizations interested in environmental justice. A user of this map would be able to look up ENGOs in their area and find those that might align with their EJ values. Researchers and ENGOs can utilize this one-of-a-kind resource to provide support to ENGOs in underserved areas. ENGOs may also be able to look up the map and connect with other ENGOs, based on their EJ value, to build coalition networks. More significantly, for students like Tasmia, who felt like they couldn’t express their environmental experiences or worldviews, the map will help underrepresented youth identify ENGOs across Ontario that might support their vision for environmental justice, thus revealing paths to belonging and purpose. Future phases of this work will assess this hypothesis by tracking how youth engage with the map to seek connection and engagement.

Tasmia Jamil and Praneeta Mudaliar

Mississauga

References

- Taylor, D., (1992). Can the Environmental Movement Attract and Maintain the Support of Minorities In Eds. Bryant, B., and Mohai, P., Race and the Incidence of Environmental Hazards.

- Kashwan, P., & Hasnain, A. (2024). Decolonizing environmentalism: alternative visions and practices of environmental action. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Schlosberg, D. (2007). Defining environmental justice: Theories, movements, and nature. Oxford University Press.

- Whyte, K. P. (2011). The recognition dimensions of environmental justice in Indian Country. Environmental Justice, 4(4), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2011.0036

- Nature Canada. (2021, May 25). Nature Canada reflects on Black Lives Matter, racism and the environmental movement. https://naturecanada.ca/news/statements/anti-racism-and-the-environmental-movement-reflection/

- Doyle, T., McEachern, D., & MacGregor, S. (2016). Environmental non-governmental organizations. In Environment and Politics (4th ed., pp. 116–148). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203383704-5