This blog was written by Xiaoqian ZHOU, supported by Kyungmin Lee, ICLEI East Asia Secretariat

Have you ever taken a suit or school uniform to the dry cleaners and considered how that might relate to the air we breathe? It may sound surprising, but the chemicals used in dry cleaning don’t just work to clean clothes; they also release substances known as Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). These compounds easily evaporate into the atmosphere, contributing to the formation of ozone.

While ozone is often associated with the protective layer high in the sky, it can actually be more harmful to human health than fine dust when it lingers near the ground. High levels of ozone can irritate the eyes and respiratory system, increase the risk of respiratory diseases, and even harm crops and buildings.

The challenge is particularly significant in Seoul, the bustling capital of the Republic of Korea, where the economy is primarily service-based and has a high density of small businesses, such as dry cleaners. The frequent use of formal wear, school uniforms, and limited in-home laundry space drives the popularity of dry cleaning. Beyond dry cleaners, other urban activities—like car usage, road paving, printing, and painting—also generate VOC emissions. All these factors combine to make ozone management a persistent issue for the city.

But dry cleaning also tells a story of change. Through a government-supported project, some laundromats in Seoul have switched to eco-friendly machines that use silicone instead of traditional dry-cleaning solvents, such as perchloroethylene (PERC).

The Green Earth Cleaning Oksoo branch, for instance, replaced old machines with new ones that eliminate VOC emissions without raising prices for customers. As a staff member put it: “There is no difference in the price for the laundry after we changed to the eco-friendly machines, and since VOCs and harmful substances are no longer emitted, it’s a healthier environment overall.”

Photo ©Xiaoqian ZHOU, ICLEI East Asia

Seoul has faced challenges beyond just ozone in its quest for clean air. Two decades ago, the overall air quality in the Seoul Metropolitan Area (SMA) was disheartening. Levels of fine particulate matter (PM) were between 1.7 and 3.5 times higher than in other developed capital cities, while nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) concentrations were about 1.7 times elevated as well. Furthermore, when compared to non-metropolitan areas in Korea, NO₂ levels in the SMA averaged over 40% higher.

The health consequences were alarming. In the year 2000, air pollution was responsible for nearly 1,940 premature deaths in Seoul. Fine particulate matter, such as PM2.5, has been linked to serious conditions like asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia, heart disease, and stroke, particularly affecting children and the elderly. The World Health Organization has classified PM2.5 as a carcinogen, underscoring the increased risk of respiratory cancer.

The financial cost was just staggering. The social damage from air pollution in the SMA was estimated at 8.6 trillion KRW annually, rising to 12 trillion KRW when fugitive dust was included. The cost of treating health issues such as respiratory and cardiovascular diseases due to air pollution places a significant economic burden on both the government and individuals.

And beyond money or health, poor air quality eroded everyday life. Citizens avoided walking or cycling outdoors, while surveys revealed higher levels of stress and depression on days with poor air quality. Additionally, several studies show that periods of high ozone and fine dust levels increase dissatisfaction, depression, and anxiety among residents.

Faced with this crisis, the Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) rolled up its sleeves. Since the early 2000s, they’ve implemented targeted strategies, starting with the 2003 Special Act on Air Quality Improvement and subsequent Basic Plans. In September 2022, Seoul unveiled the “Clearer Seoul 2030”, a comprehensive plan to strengthen air quality improvement policies to accelerate the shift to electric vehicles, restrict polluting vehicles, and phase out internal combustion engine vehicles.

Key actions include the ‘Seasonal Management of Fine Dust’ during winter highs:

- Banning emission-heavy vehicles without upgrades and enforcing emission/idling checks, plus DPF maintenance.

- Rewarding companies with traffic charge reductions for car-free initiatives like odd-even systems.

- Cracking down on dust from pollutant facilities and construction sites.

- Promoting heating limits (18°C for public buildings, 20°C or less for private) in energy-guzzlers.

- Boosting road cleaning on busy highways using electric sweepers.

They also pushed low-emission projects:

- Early scrapping of high-polluting Grade 4 and 5 diesel vehicles and old construction machinery, with subsidies based on type, model, and age.

- Installing reduction devices like DPF and PM-NOx, plus electrifying equipment for zero-emission sites.

These efforts paid off big time. Emissions of most air pollutants have plummeted since 2000, and atmospheric concentrations of major ones have improved. Nationally, air quality has improved steadily over the past six years. In the latest Fine Dust Seasonal Management Period (December 1, 2024, to March 31, 2025), the average PM2.5 concentration hit a record low of 20.3 µg/m³—down 3.3% from the prior year and the best since the plan’s 2019 start, according to the Ministry of Environment. At this “normal” level, daily activities are generally safe, though sensitive folks with respiratory issues should mask up for long outdoor stints.

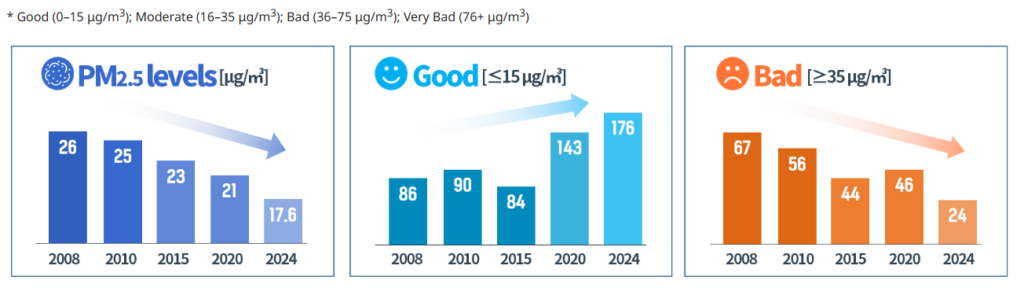

In 2024, Seoul achieved its lowest recorded level of particulate matter (PM2.5) since the implementation of PM management in 2008. The city reduced its annual average PM2.5 concentration by approximately 32%, decreasing from 26 μg/m³ in 2008 to 17.6 μg/m³ in 2024. Additionally, the number of days with ‘good’ air quality more than doubled from 86 to 176, while days classified as ‘bad’ or worse fell to just 24, representing a reduction of roughly one-third.

Seoul’s story illustrates the significant impact that can be achieved when policies, businesses, and citizens work together. Cleaner air has led to fewer premature deaths, lower economic costs, and increased opportunities for outdoor life under blue skies.

Yet, challenges like VOCs remind us that work isn’t done. To consolidate gains, cities should opt for innovative solutions, for example, supporting green laundries. Taken together, these measures can sustain air-quality improvements and deliver lasting health and economic benefits under bluer, cleaner skies.