By Tom Rademacher

When I was a middle schooler, I cared about two things: Kurt Cobain and talking with my friends (largely about Kurt Cobain). We were still a few years away from AOL Instant Messenger, and a solid decade before texting would become popular.

When I was a middle schooler, I cared about two things: Kurt Cobain and talking with my friends (largely about Kurt Cobain). We were still a few years away from AOL Instant Messenger, and a solid decade before texting would become popular.

To us, then, school-day socializing was contained to passing time between classes, lunch, and the occasional field trip during which months’ worth of interpersonal drama would be crammed into the galleries of the Milwaukee Art Museum.

No one reading this needs me to tell them how things have changed, how constant and immediate access to social connection, reward, and harassment has re-shaped the experience of our students and schools.

Now, we’re in a new wave. Schools across the country are increasingly banning cellphones, and so far, the results are tending towards positive (which could just mean the kids have all agreed not to tell us how they’re getting around the ban, but let’s do positive thinking for now).

All these cellphone bans do beg one particularly important and difficult question: Now what?

When I was a kid, my dad quit smoking about 100 times. He tried the gums and the patches and everything he could, but he only quit for good when he started going to dog parks. He was used to taking a lunch break in his car, listening to music on the radio and smoking a cigarette.

Removing the cigarette but not the environment made the work of not-smoking entirely too hard. So, on quit attempt 100, he stopped taking his lunch break in his car and instead went to the dog park down the street. He’d walk around, watch the dogs, avoid the humans, and forget about how he wasn’t smoking.

Filling the Sudden Chasm Left by Phones’ Exit

Schools are finding out that it’s not enough to take the phones away. We need to make sure there are energizing, collaborative, challenging things to do. We need to change what it feels like to be in school enough to make it easy, or at least easier, for students to not-phone.

Below are my very favorite strategies that don’t use screens and that students have talked about and used for years after they had me as a teacher. You can use these strategies on a broad range of content and for a broad range of students and can use them over and over as students develop them as a tool for deeper learning.

I shared these strategies and others in 50 Strategies for Learning without Screens, and although they are not just phone but completely tech-free, they focus on the kinds of skills students need to be successful in an increasingly digital world: curiosity, creativity, collaboration, compassion, and critical thinking.

Critical Thinking with Scissors

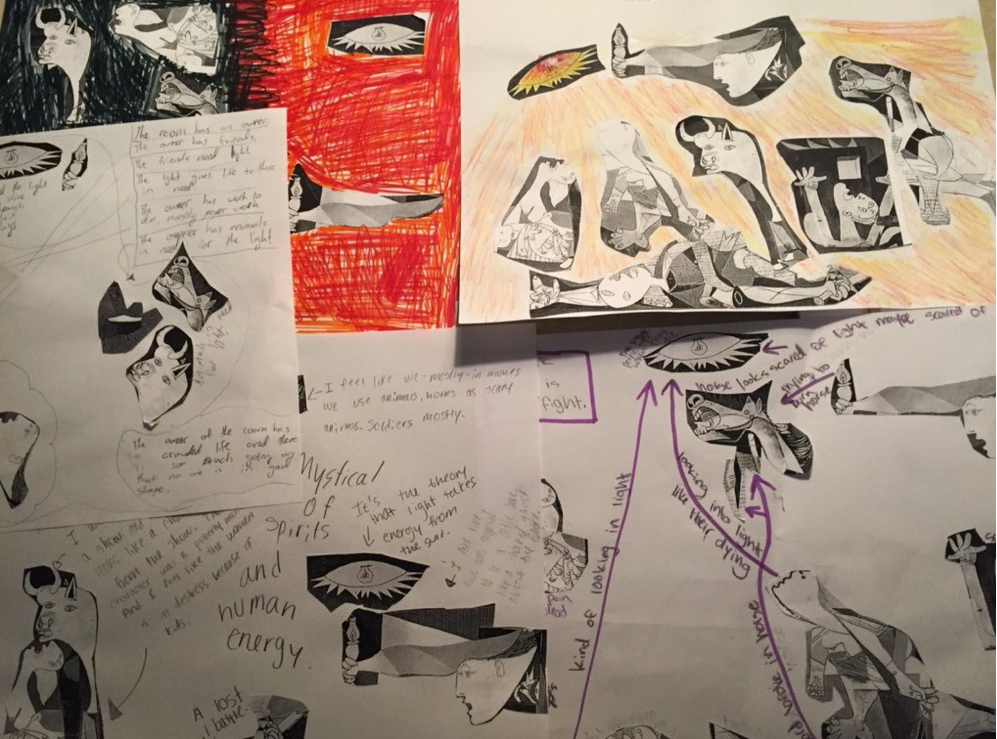

Deconstruction is a critical and difficult component of analysis. Whether you and your students are taking apart a new and difficult concept, an important passage, or a visual text, you can make the abstract a lot more concrete with some scissors and glue.

Hand each student a copy of the text and a larger blank sheet of paper and instruct them to cut the original into its “building blocks” or elements. Next, have them reimagine the text by placing its pieces on the blank page in a way that shows how they understand it. They could make a flowchart, place ideas in groups, or use some other creative approach to show the meanings they found.

I used this strategy to practice critical analysis using Picasso paintings or other artworks with lots of subtext and visual metaphor. Each student creates a visual, using pieces of the original to show what they think the painting means. (It helps to assure them there is no right answer.)

Frayer Models

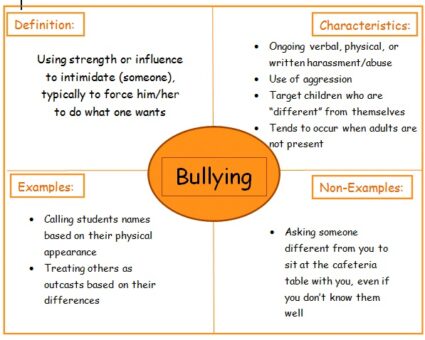

Developed by Dorothy Frayer and her colleagues in 1969 at the University of Wisconsin (Go Badgers!), a Frayer model is a deceptively simple tool for tackling complex ideas. It helps students define or clarify the meaning of vocabulary words. The Frayer model is a square divided into four smaller squares. Starting at the top left square and working clockwise, the boxes are labeled “examples,” “nonexamples,” “nonessential characteristics,” and “essential characteristics.”

No matter what a student suggests, it should fit somewhere in this model. Frayer models work well in small groups because they spark rich discussion about where a specific word should go. For example, if the concept you are defining is “breakfast,” where does “pizza” go? How about “morning?”

With vocabulary words, a Frayer model might also be labeled “definition,” “characteristics,” “examples” and “non-examples” – like this:

I love the discussions and the thinking that Frayer models inspire around seemingly simple concepts. Starting simple is also important so that students have mastered the tool when they move on to defining more complex ideas. (I’ve seen or used Frayer models to create class definitions of terms such as racism, intelligence, art, and American.)

Using a Frayer model to create class definitions can open a conversation about why mutual understanding of a word is important before discussions and debates and can show how any definition of a word is not necessarily the “right” one.

Crayon Quiz

This no-tech strategy provides all the things that are most important about any short comprehension quiz. It allows students to reflect on the work they’ve done that week, make sure they understand key concepts and ideas, and spend some time talking about it with each other.

A crayon quiz is perfect for a Friday or anytime the brains and bodies in the room need a little break, but you still want to do something meaningful. The key components are as follows: minimal instructions, a few big sheets of paper, and a whole bunch of crayons.

On the board, write a list of things each group must share from the reading from that week, such as important scenes, characters, and plot points. Give each group a certain number of elements they must contribute. For example: three quotes, three drawn images, and two symbols. Or, instruct students to create their own combination of elements that summarize their learning of a specific topic or unit. The crayons reduce the quizzyness.

Sticky Linguists

Have you ever used a new slang word or texted an emoji to a younger person and done so slightly wrong? If so, then you already know that young people are accomplished linguists. Their grasp of the rules of language in their lives is often far more complex than they realize. Help them articulate what they know about the structure of language with this strategy.

Have you ever used a new slang word or texted an emoji to a younger person and done so slightly wrong? If so, then you already know that young people are accomplished linguists. Their grasp of the rules of language in their lives is often far more complex than they realize. Help them articulate what they know about the structure of language with this strategy.

Have students work as a group to brainstorm words on any topic and write each word on a sticky note. Then challenge them to come up with their own categories for the words and explain their reasoning. Sit back and listen; you will hear some truly incredible insight and investigation into the parts of language. This strategy is perfect for exploring words around identity, activating background knowledge on a topic, or exploring parts of speech.

Budding adolescent sociologists love to study and question the world around them. Ask them to brainstorm words that are used to describe young people, people from your region, or other aspects of identity (depending on the level of trust and safety the group feels with you and each other). This activity can help them see how language is used to build the world they live in.

*These strategies are adapted from 50 Strategies for Learning without Screens. For a free download of four additional strategies, go to my Curiosity-Sparking Classroom Strategies Guide at the TCM website.

Tom Rademacher has spent the last two decades devoted to students and education. He’s the author of 50 Strategies for Learning without Screens, It Won’t Be Easy, Raising Ollie, and the forthcoming chapter book series Bucket and Friends.

Tom Rademacher has spent the last two decades devoted to students and education. He’s the author of 50 Strategies for Learning without Screens, It Won’t Be Easy, Raising Ollie, and the forthcoming chapter book series Bucket and Friends.

Tom was named Minnesota’s 2014 Teacher of the Year, and before teaching mostly wrote bad poetry and talked about Kurt Cobain. He lives too close to the Mall of America in Minnesota with his wife, son, and absolute chonk of a dog.

Feature image from Peninsula’s cell phone policy a model for nearby school districts by Conor Wilson,Gig Harbor Now, October 10, 2024.