I recently visited the site of the Potomac River Sewer Spill — what is now likely one of the largest accidental sewage spills in U.S. history. Given the ice and snow still on the ground, it was a challenge to get to, but I immediately knew I was going in the right direction because the smell kept getting stronger.

I bumped into someone that lives nearby who was also walking to inspect the damage. When we finally arrived at the site, we were both a little taken aback by how much equipment was there. Several massive pumps are taking raw sewage out above the breach in the Potomac Interceptor pipe — a massive 72-inch concrete pipe — and putting it into the C&O Canal, which runs parallel where to the river. From there the sewage flows down about a quarter of a mile before it is re-routed back into the undamaged portion of the interceptor pipe.

It’s funny how sewage doesn’t look like you might think — rather than a brown sludge, it’s very gray colored water. This is due to the quantity of water going down our drains, which washes everything through the pipes. However, you can tell this is definitely sewage both by smell, and the amount of toilet paper and “flushable” wipes you see getting caught up on sticks and branches in the canal. These wipes aren’t actually flushable and can wreak havoc on our rivers and water infrastructure even when there’s not an emergency. This was the driving motivation behind the introduction of the WIPPES Act in Congress last year.

Normally, the pipe transfers roughly 40 million gallons of sewage every day. When the pipe failed on January 19, massive amounts of sewage poured into the canal, which then overflowed, sending sewage into the Potomac River. Over the course of 10 days, before the site was contained, it’s estimated between 200 to 300 million gallons of sewage ended up in the river. That’s like filling every bathtub in the nation’s capital with sewage, many times over, and then letting it all run into the river.

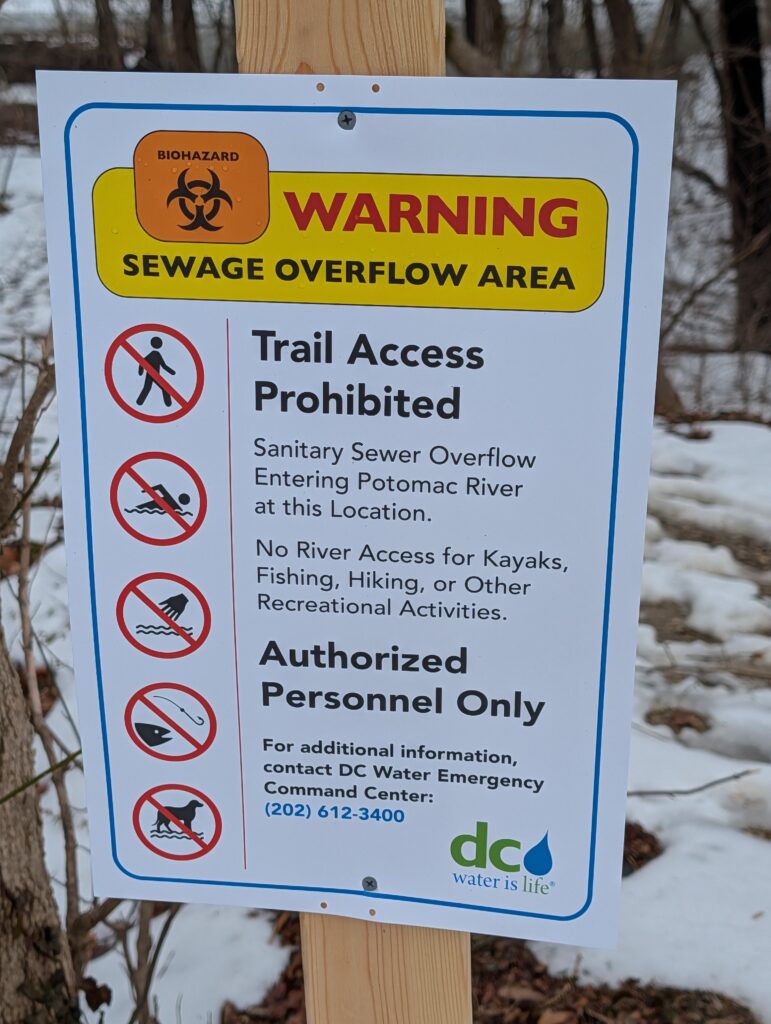

Fortunately, according to D.C. Water, drinking water supplies were not impacted, but the spill caused health advisories and urgent warnings to avoid contact with the water in both the river and the Canal. While necessary, this is a disappointing development as the Potomac is widely used for recreation — be it kayaking, rowing, rafting or boating.

Our partners, Potomac Riverkeeper Network, have been tirelessly collecting data and finding that in the midst of the overflow, bacteria levels in that stretch of the river skyrocketed to over 4000 times the safe recreational level. It’s too early to say what the long-term impact on the Potomac will be — some sewage was frozen during the recent cold weather, and as that melts we could see bacteria levels spike again. It’s also possible that other pollutants commonly found in sewage — forever chemicals, pharmaceuticals, etc — will end up settling into river sediment, killing or poisoning the fish, birds and insects that live in those stretches of the river.

If you live in this area as I do, the C&O canal area is a popular area to walk, bike, and access the river for fishing and boating. It’s part of the National Park System. We have been taking our kids there ever since they were toddlers. I can still picture my daughter giggling at the sight of a Blue Heron grabbing a fish there. While the sewage overflow is no longer flowing into the river (for now), the historic canal is being used as a bypass for the sewage. There is a literal river of sewage flowing open along the towpath that parallels the canal. The estimated repair time is going to be 9-10 months, disrupting the communities nearby. This doesn’t include time for the environmental remediation (removing contaminated soil, etc.) that will have to be done on the area afterwards.

The most frustrating thing about all of this is how preventable it all was. That sewer line was built in the early 60’s and it was already known to be past the end of it’s service life. That’s why D.C. Water was in the process of replacing parts of it; ironically the section that failed was due to be replaced this spring. If only we had invested in repairs a couple of years ago.

And that’s the rub — this is a problem for the entire country — we don’t invest enough in sewer infrastructure repairs. Instead we tend to react crisis by crisis, instead of being proactive. The American Society of Civil Engineer’s Bridging the Gap report states that over the next 20 years, we will have a $270 billion funding gap for sewer system repairs and a $176 billion gap for stormwater systems.

Let’s Stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Mid-Atlantic for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

None of these sewer system collapses are inevitable — we have the technology and the know-how to understand where repairs are needed and when. Most of the problem is the lack of funding and political will. Which sadly means, unless we get our act together, there will be more of these spills in our future.