Urban cemeteries such as Lakshmipuram serve diverse important purposes. By bringing the ecological, social, historical, and sacred together can bridge nature and culture of cities.

The word “cemetery” is derived from the Greek word ‘koimeterion’ meaning ‘dormitory’ or “resting place”. But cemeteries in cities can be more than resting sites for the deceased, or for their loved ones to visit and mourn. They are spaces that harbour a rich biodiversity including trees and plants of conservation value. Famous cemeteries also attract a large footfall of visitors, such as the Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris, France, where a galaxy of famous artists, authors, and musicians are buried. As Francis et al (2000: 43) say, cemeteries can play an important role in “anchoring cultural communities”. The Lakshmipuram cemetery situated in Ulsoor, at the centre of Bengaluru, is one such space―where multiple urban worlds collide.

Over the years, we have visited the Lakshmipuram cemetery in Bengaluru, which covers 7.07 ha, documenting tree diversity, and learning about the social and cultural significance of this cemetery for residents of the city.

Tree diversity of Lakshmipuram cemetery

During a research study of Bengaluru’s cemeteries (Jaganmohan et al. 2018), we counted a total of 556 trees of 15 species in Lakshmipuram cemetery, of which eight were introduced and seven were native species. Most trees (504 of 556 trees) belonged to native species, with the Indian beech (Pongamia pinnata) accounting for as much as 83 percent of all trees. We spoke to a grave designer, who told us that many visitors who buried family members in the cemetery paid him to plant a tree near the grave ― and they prefer the Indian beech. He attributed the abundance of this species in the cemetery to this practice.

Photo: Seema Mundoli

Other commonly seen native species were banyan (Ficus benghalensis) and peepul (Ficus religiosa), both of which are of cultural and sacred value, especially to Hindus (this is a Hindu cemetery). There were also jamun trees (Syzygium cumini), and wood apple trees (Limonia acidissima); the latter is a species believed to be sacred to the Hindu God Shiva, in whose honour the Maha Shivaratri festival is celebrated each year at the cemetery. The other native species were the Pride of India (Lagerstroemia speciosa), and the Indian mast tree (Polyalthia longifolia). Among the introduced species were Indian siris (Albizia lebbeck), cook pine (Araucaria cookii), pink cassia (Cassia nodosa), golden cassia (Cassia spectabilis), sausage tree (Kigelia pinnata), Nile tulip (Markhamia lutea), raintree (Samanea saman), and African tulip (Spathodea campanulata).

Photo: Seema Mundoli

The cultural significance of Lakshmipuram cemetery

The Lakshmipuram cemetery is of special cultural significance to communities from Ulsoor, as well as for those who have moved away, but who still have family members buried there. While the exact origins of the cemetery are unclear, we found a grave dated 29 September 1887, indicating that the cemetery is of considerable antiquity.

Photo: Seema Mundoli

Our visits and interviews focused on the annual festival of Maha Shivaratri―a celebration at the Lakshmipuram cemetery that transforms the otherwise quiet space into a bustling fair. The festival of Maha Shivaratri is held in spring on a new moon night to commemorate the marriage of Lord Shiva to the Goddess Parvati. Shiva is a very important god in the Hindu pantheon who is seen as a creator, protector, and destroyer. The festival begins with the worship of Shiva followed by that of his consort Parvati, the next day as Kali, the destroyer of evil. The priestess explained the significance, saying:

“We perform puja there [cemetery], because, the Goddess Parvati and Shiva will be together only in the graveyard. When Shiva takes his angry form in the graveyard, he can be pacified only by Goddess Parvati. So we first worship Shiva until 12 am, then the goddess after that.”

On the night of Maha Shivaratri, devotees stay awake, praying, meditating, and chanting hymns in praise of Shiva. In Lakshmipuram, the day following the all-night vigil is celebrated in a unique fashion, with a visit to the temples in the cemetery, followed by offerings of food and drink by family members to the graves of their loved ones.

There are six temples in the cemetery. Four are dedicated to the female Goddess Kali (considered to be a form of Parvati), while one is a shrine to the snake gods and the last is a Satyaharishchandra Temple, dedicated to a legendary Hindu king known for his honesty and righteousness. Perhaps the most spectacular of the Kali idols, and one that forms the centre of the Maha Shivaratri festival, is the one of her lying supine on the floor. This idol is made of mud and is shaped to take the form of the goddess 15 days prior to this festival. This Kali has a disproportionately large head, and a truncated torso and legs. The eyes and nose are large, and the mouth is shaped into a hole. On this festival day, the idol is decorated with coloured cloth, and strewn with flowers.

Photo: Seema Mundoli

Several rituals take place around the Kali idol. The priestess blessed lemons that were stepped on, and eggs and cucumbers were waved around the head and touched on the shoulder of the person to ward off the evil eye. Another ritual involved specifically protecting young children from the evil eye and illness. The assistant to the priestess carries a child and places the child briefly on a cloth laid out near the open mouth of the Kali. Chickens were also offered for sacrifice by devotees. We observed several locks on the grills around the enclosure where the idol lay. We were told that the locks were offerings by devotees seeking intervention in resolving fights and altercations. Explaining the reason for the locks, the priestess said:

“It is a symbol to close people’s mouth. If someone is talking ill of us behind our backs, we take their name and put a lock there in the temple. Two people have told me that this has actually worked. I had to remove the locks as they told me that they could not talk.”

Photo: Seema Mundoli

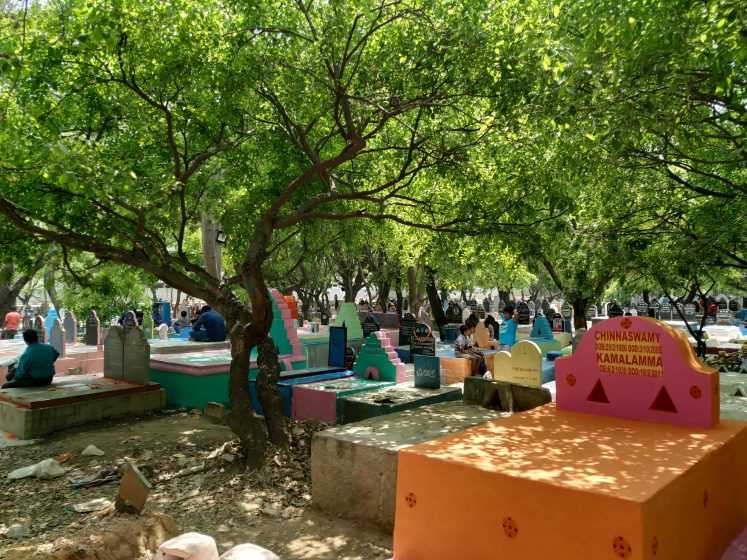

While the temple witnesses a steady stream of devotees, worship at individual graves was also being carried out. In the days leading up to Maha Shivaratri, family members visit the cemetery to clean the area around the graves, removing fallen leaves and any trash. The graves range from simple mud graves with no headstones, to large graves made of expensive granite, some with elaborate headstones that have photographs of the deceased. The family members repair the graves, decorate them with flowers, and paint them. Splashes of red, pink, yellow, blue, and orange from freshly painted graves provide a visual contrast with the fresh green leaves of the Indian beech that shades many of the graves. Graves are decorated with simple floral or geometric patterns. We also saw some interesting drawings—for example one of the graves was painted in the hues of the Brazilian flag with a design of the flag and a football.

Photo: Seema Mundoli

During worship, family members place lit earthen lamps and lit incense sticks on the graves, or in the triangular alcoves that some of the graves. They apply turmeric and vermilion in dots and stripes on the graves and use rice powder to draw patterns on the graves.

Photo: Seema Mundoli

An important aspect is to provide offerings of food and beverages to the deceased. Family members prepare food at home, or occasionally purchase food from outside, placing these in plates made of leaves, plastic, and paper on the graves. The food served could be the food cooked at home that day, but often special, multi-course meals were provided, sometimes taking care to include the favourite food of the person buried. We observed a variety of food placed on the graves, ranging from a homemade traditional meal of ragi mudde (a dish made of finger millet, Eleusine coracana) to cake purchased from local bakeries. Beverages including water, buttermilk, and juice were placed on the graves. We even observed a couple of graves with bottles of beer, and alcohol poured into glasses. The visiting family members ate some food at the grave. What was left was collected by young boys waiting eagerly around, and beggars. Dogs ate their fill of food, dozing on the graves afterwards, while crows (Corvus splendens) and black kites (Milvus migrans) circled the air and looked on from the trees, grabbing pieces of meat and other food once people moved away.

Photo: Seema Mundoli

Photo: Seema Mundoli

On the day of the Shivaratri festival, the path from the entrance of the cemetery to the temples was filled with vendors selling snacks, ice cream, and candy floss. Others were selling inexpensive plastic toys and vessels of steel and aluminium. In 2019, the local corporator helped install a large LCD screen that was playing devotional and film songs. We were also told by the interviewees about a live orchestra in the evening that was a major attraction, with the cemetery lit up with floodlights.

Photo: Seema Mundoli

After the festivities around Shivaratri end, the cemetery returns to a quiet place with hardly any visitors for most of the year. Some visitors do come to pray at the festival of Ugadi, locally celebrated as the New Year, which falls between late March and early April. Family members also visited the graves during the birth and death anniversaries of those buried at the cemetery to pay their respects. Women came during the year to pray for a good marriage, and for a child, at the nagarkallus (snake shrine). An Indian beech at the snake shrine was tied with sacred threads. The base of the shrine was surrounded by several small cradles, fertility offerings to the snake god.

Photo: Seema Mundoli

Lakshmipuram cemetery as a social space

The cemetery was home to three families who resided within the premises, in charge of burials. We saw children and adults from these families during our field visits. Sometimes there were visitors who came with a specific purpose. The grave designer spoke of a neighbour, a lady whose daughter was buried in the cemetery. Every year, on her daughter’s birthday, she would take a cake to the cemetery, invite her neighbours to join her, and cut the cake next to her daughter’s grave―almost like a picnic according to the grave designer. The grave designer said:

“Yes, sometimes we get the departed people in our dreams. When that happens, we go to visit the person’s grave and ask them what the problem is. My wife goes to visit our son’s grave like that.”

Photo: Dechamma CS

In our interviews with some of the visitors to the cemetery on the Maha Shivaratri festival day, they reminisced about their childhood and said that they used to come to play cricket in the cemetery. We were told that youth from the area continue to play cricket in an open patch in the cemetery. The grave designer also said that,

“There are some local youths, who drink and smoke and play cards in one corner of the cemetery. I have also seen some destitute people sleeping inside. When I asked one of then he said he sleeps well inside.”

We attended a cultural event at the cemetery ― Karagadhe Kathegalu (stories of the Karaga). This event was organised by The Aravani Art Trust, an NGO that uses art as a medium to create awareness about the transgender community and women’s issues. The Karaga is a festival celebrated by some local communities, is dedicated to Draupadi from the epic Mahabharatha. In the ritual, a man dresses up as a woman and dances carrying an elaborately decorated pot embodying Draupadi. In this event at the cemetery, a man dressed up as a woman performed with members of the transgender community. At the event, the organisers explained the connection between cemeteries and transgendered people, who face extreme discrimination from family members and society and are excluded from accessing public spaces such as parks that are open to others. The cemetery is one location in the city where the community feels safe, not shouted at or shooed away, and not judged. For the community, the cemetery is a place where they can find peace before and after death.

Photo: Sukanya Basu

Cemeteries are for the dead, but can be also for the living

Cemeteries can be quiet, tranquil places that allow for reflection, or social sites used for recreation by urban residents. They can be of sacred or cultural significance, or be habitats for different kinds of biodiversity both floral and faunal especially native species that reflect the ecological history of the city. They can be places to mourn the dead or be sites that enable encounters between different cultures and religions in a heterogeneous urban community (Swensen and Skår 2018, Swensen 2018). Or, as the case of Lakhsmipuram cemetery has shown, serve diverse purposes―sacred, cultural, social, and ecological. Above all, urban cemeteries such as Lakshmipuram by bringing the ecological, social, historical, and sacred together can bridge nature and culture of cities.

Seema Mundoli and Harini Nagendra

Bengaluru

About the Writer:

Harini Nagendra

Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Sustainability at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India. She uses social and ecological approaches to examine the factors shaping the sustainability of forests and cities in the south Asian context. Her books include “Cities and Canopies: Trees of Indian Cities” and “Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities” (Penguin India, 2023) (with Seema Mundoli), and “The Bangalore Detectives Club” historical mystery series set in 1920s colonial India.

Acknowledgements

We thank Muthyalappa Lakshmi for first introducing us to the Lakshmipuram cemetery, sharing her memories, and taking us with her to witness the ceremonies. We are grateful to all who spoke to us for their time and inputs. We thank Manujanth B, Varsha Bhaskar, Kshiraja Krishnan, Dechamma CS, and Sukanya Basu for their assistance with field visits, Enakshi Bhar for preparing the study area map, and Azim Premji University for funding this research.

References

Francis, D., Kellaher, L., Neophytou, G. (2000) Sustaining cemeteries: The user perspective. Mortality, 5(1): 34–52.

Jaganmohan, M., Vailshery, L.S., Mundoli, S. Nagendra, H. (2018) Biodiversity in sacred urban spaces of Bengaluru, India, Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 32: 64–70.

Swensen, G. (2018) Between romantic historic landscapes, rational management models and obliterations: Urban cemeteries as green memory sites. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 33: 58–65.

Swensen, G., Skår, M. (2018) Urban cemeteries’ potential as sites for cultural encounters. Mortality, 24 (3): 333–356.

About the Writer:

Seema Mundoli

Seema Mundoli is an Assistant Professor at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru. Her recent co-authored books (with Harini Nagendra) include, “Cities and Canopies: Trees in Indian Cities” (Penguin India, 2019), “Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities” (Penguin India, 2023) and the illustrated children’s book “So Many Leaves” (Pratham Books, 2020).