Greening a city is not just about the aesthetic; it’s about creating an environment that supports people, wildlife, and our planet.

about the writer

Louisa Ward

Louisa is currently a research assistant at the University of Surrey, working in collaboration with Tranquil City. Having completed her BSc in Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Nottingham, she became interested in research from a behavioural science perspective. As a result, she then went to study an MSc in Behaviour Change at the University of Surrey. Her interests include understanding the barriers preventing engagement with nature, and what aspects of an intervention facilitate change.

about the writer

Eleanor Ratcliffe

Eleanor Ratcliffe is a Senior Lecturer in Environmental Psychology and a Fellow of the Institute for Sustainability at University of Surrey, UK. She is a Board member of the International Association of People-Environment Studies and programme lead for Surrey’s MSc Environmental Psychology.

about the writer

Grant Waters

Grant Waters is the CEO of Tranquil City, an environmental research and innovation company, with a mission to bring people in cities closer to nature and to create healthier urban environments. He has extensive experience in coordinating multidisciplinary innovations that bridge gaps between research, practice and positive impact.

Having grown up on a farm, the presence of nature was something I took for granted before transitioning to city living. Sitting back in the comfort of the countryside, a simple glance out the window revealed red kites flying over the woodland, and goldfinches nesting in the wildflowers. But this picturesque countryside scene stands in stark contrast to the years spent living in the city, where the most memorable example of urban wildlife was a one-legged pigeon (for more on urban pigeons and their toes, see Jiguet et al., 2019).

Urbanised societies have increasingly stepped away from nature. For many years, this emphasis on city living has benefited society by generating jobs and technologies, and bringing together people from all backgrounds. None of this is to be undervalued, of course, but this shift comes at a cost. As cities expand and urbanisation continues to rise, nature is pushed out of sight, with knock-on effects for the environment and detrimental effects on our wellbeing.

Why nature in cities matters

Research has shown that spending just two hours each week in green spaces is enough to support good health and wellbeing (White et al., 2019). In addition to benefiting people, nature plays a key role in improving the quality of air, improving urban biodiversity, and reducing air temperature within urban environments (Raymond et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2025). It has been projected that nearly 70% of the population will be living in urban environments by 2050 (United Nations, 2018). As a result, we must find ways of living in synchrony with nature if city living is to be both sustainable for the planet and our wellbeing. The reality is, nature isn’t just “nice to be around”, it’s essential.

It is important to note that certain groups may experience greater benefit from access to green spaces. The European Environment Agency has suggested that people from lower socio-economic status (SES) groups may experience higher levels of stress reduction and greater improvements in mental health from spending time in nature compared to those of higher SES groups. Initiatives such as allotments or community gardens can support socialising, growing healthy foods, and opportunities to learn about the environment (Camps-Calvet et al., 2016). Unfortunately, people in lower SES groups tend to have lower access to high-quality green spaces (Mears et al., 2019; Baka & Mabon, 2021). It’s therefore important to support access to high-quality green spaces for all demographics, and not just for those living in high SES areas, so that the benefits of nature can be shared more equitably.

Enter Tranquil City: The organisation with a vision

London-based organisation Tranquil City is on a mission to re-green cities and remind us of the benefits of being surrounded by nature in all its glory. With a clear understanding of urban challenges and using an evidence-based approach, Tranquil City has designed a framework and toolkit for conducting environmental research, with the aim of making nature accessible for all.

The Make My City Thrive (MMCT) framework is a multidimensional approach for evaluating nature-based interventions in urban settings. It isn’t just about planting more trees. It creates a systematic and structured way of thinking, considering elements which are believed to be necessary for a city to not just exist, but to thrive. It is measured across seven key components. These cover how spaces are designed, how individuals interact with these spaces, and the subsequent impacts on wellbeing. In short, the MMCT Framework turns the abstract and complex concept of city greening into something measurable and actionable.

Grant Waters, CEO and Co-founder of Tranquil City, says, “The positive impact of urban greening interventions is generally said to be ‘a given’. However, in our experience, interventions are not made equal, and it’s essential to be able to measure and understand the effect a landscape design has on wellbeing and engagement to optimise how towns and cities can support people to live healthy lives. Does an intervention boost people’s mood? Does it improve people’s perception of a local area? Is it appealing and accessible to all? How does it improve the wellbeing of people in the local area over the long term? These are all questions that we can now answer when applying the Make My City Thrive framework. It’s helping provide an evidence-base for in-situ urban greening that can help guide design and planning towards positive health outcomes, but also help make the economic case for such measures to be implemented.”

The toolkit for greener cities

So, how does this framework help to deliver measurable benefits for people?

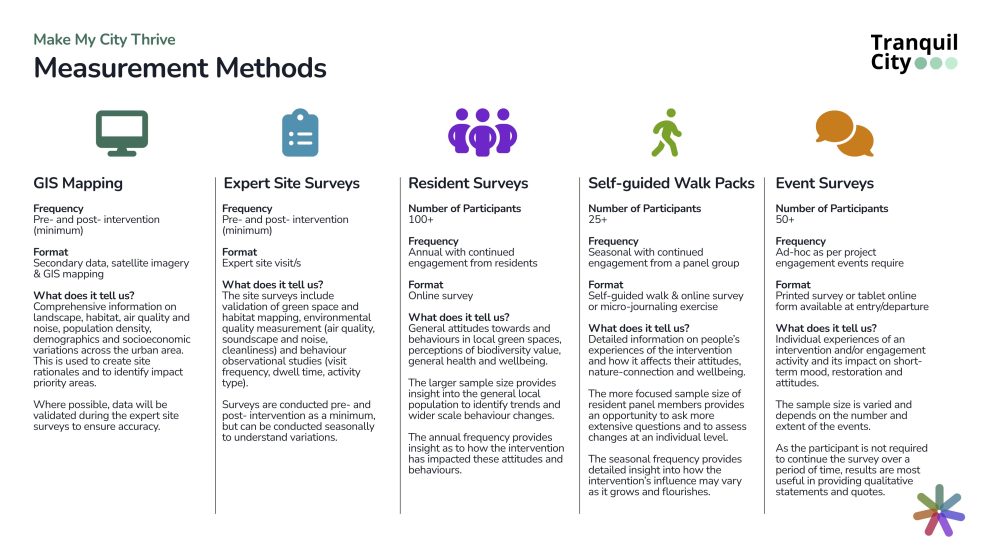

It’s time to introduce the “Measuring the Tranquil City” Impact Assessment Toolkit, designed in collaboration with Dr Eleanor Ratcliffe, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Psychology at the University of Surrey, and supported by a British Academy Innovation Fellowship. This is a practical guide to evaluating urban greening in real-world urban environments, making use of objective environmental data, as well as subjective data about people’s thoughts and feelings (captured quantitatively, using rating scales, and qualitatively, in people’s own words). It is designed to be used in collaboration with organisations that want to better understand how people experience environments in their care. This might include taking a “snapshot” of one moment in time or understanding changes in experience before and after a nature-based intervention. Whether it’s a pocket park in a housing estate, or a green corridor in a city centre, the toolkit is designed to guide planning, data collection, and analysis, ensuring results are robust, reliable, and available for public interaction.

Eleanor says, “Urban greening provides opportunities for people in cities to experience the benefits of nature and live more sustainably. Evaluation and impact assessment are key to understanding the success of these interventions―and whether they help communities who stand to gain the most. To do this properly, we need tools that are rigorous, accessible, and inclusively reflect the mosaic of different lived experiences that make up city life. That is what we’ve aimed to develop within this toolkit.”

The Impact Assessment Toolkit draws on different parts of the MMCT framework to ensure a holistic approach to research on city greening. By conducting research in this way, it recognises that individual components do not operate in isolation, and by doing so, it facilitates the understanding of any interaction between these components. Put simply, if a pocket park is designed, but only engages people from a particular background, it is not an inclusive space. By asking how spaces can be designed to ensure inclusivity for all, it leaves room for improved and intentionally designed green spaces―which results in more benefits for both individuals and communities. This is just one example of the way in which using this holistic method to research and intervention design provides an enhanced approach to city greening.

But does it work?

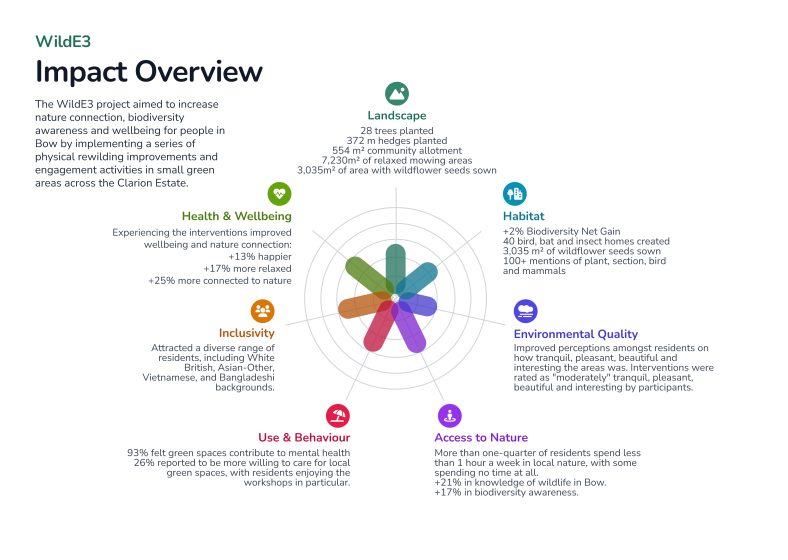

The power of the Impact Assessment Toolkit is becoming clear. Working alongside Clarion Housing Group, the WildE3 project demonstrates the potential of this method for providing wide-ranging benefits for both the environment and the community.

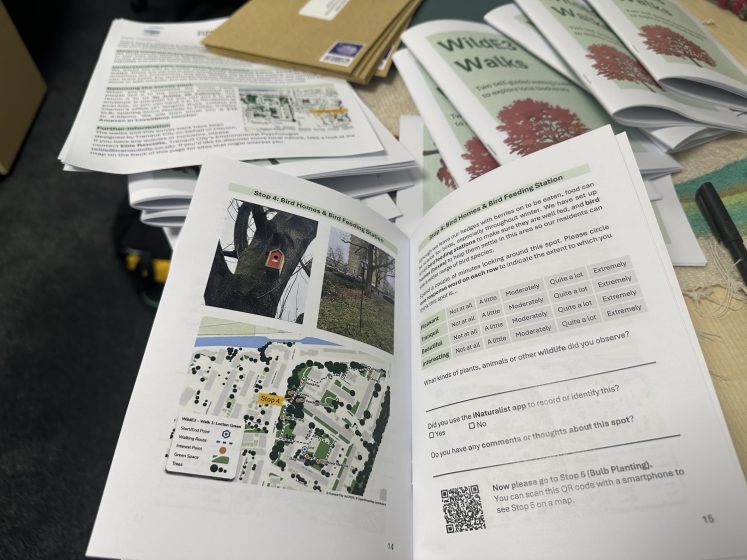

The WildE3 project aimed to increase nature connection, biodiversity awareness, and wellbeing for the people of Bow, East London. This is an area that experiences higher levels of deprivation in comparison to other parts of London. This includes lower household incomes, fewer qualifications, and higher rates of ill-health across the community. Factors such as these are often associated with fewer visits to natural spaces, which Tranquil City is attempting to change. During the project, Clarion Housing Group implemented a number of re-wilding improvements on its housing estates in Bow and invited residents to engage in activities in the newly improved green areas―including self-guided nature walks, supported by a “walk pack” that embedded evaluation surveys into the activity (pictured).

The project aimed to improve the quality and biodiversity value of nearby green infrastructure and reduce barriers to residents’ use and engagement of this infrastructure. The collaboration between Tranquil City and Clarion Housing Group was indeed successful in achieving these goals, and the MMCT framework was key in understanding the areas of improvement.

The project was recently recognised for its success at the Unlock Net Zero Awards, winning the Biodiversity and Nature Award. The project is described as “the blueprint for other areas across the UK” and has demonstrated how nature-based restoration in urbanised areas can have a wide range of benefits to both the residents and the environment. Projects such as WildE3 are just the start of the evolution towards greener cities and happier residents.

Facing the challenges.

While Tranquil City and its partners have a clear vision for a world where cities and nature can co-exist and thrive, there are barriers to making the vision a reality.

The unfortunate thing about urban greening is that there is a whole lot more to it than planting some more trees and hoping for change. A significant amount of research, urban planning, and policy writing is required for each individual project. Not only that, but implementing these designs can be costly and requires continual maintenance.

With design and upkeep of these spaces being expensive, political support is therefore required. The lack of robust data currently supporting the benefits of applied projects such as WildE3 is a significant barrier. Without data demonstrating the benefits of these interventions, it becomes difficult to gain financial or political support to implement these solutions. As a result, smaller organisations or communities may not be able to implement greening solutions if they do not have the resources or financial means to collect data on their environment. For nature-based interventions to be inclusive, they must be accessible in both deprived and wealthy areas, which is what Tranquil City aims to do.

The mission is to collect this data. With projects that are funded by external stakeholders and data collected in collaboration with Tranquil City, this research can be provided. This data can then show how beneficial it can be for both people and the place by having more green spaces within urban areas. The more data that can be collected, the easier it will be to create more spaces, and momentum can build in transforming cities into a place where both nature and the people can thrive.

The future

Greening a city is not just about the aesthetic; it’s about creating an environment that supports people, wildlife, and our planet. Tranquil City is driving change with the focus of providing the tools, data, and ultimately, the clear vision of how to reshape the urban environment.

We don’t have to decide between living in the city or the countryside. With collaboration, evidence-based frameworks, and a shared commitment to enhancing wellbeing, we can bring the city back to life. And if nothing else, we deserve to be living in a city where the most memorable aspect of the wildlife is not a one-legged pigeon.

More information is available on Tranquil City’s work here: https://tranquilcity.co.uk/

Louisa Ward, Eleanor Ratcliffe and Grant Waters

Guildford, Surrey, and London