A new kind of gold rush is sweeping the West, and this time the prize isn’t minerals but megawatts. From Phoenix to Colorado’s Front Range, data centers are arriving with outsize demands for power and water. In a new report, the regional environmental advocacy group Western Resource Advocates (WRA) warns that without stronger guardrails, the financial and environmental costs could fall on everyday households.

Across Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico and Utah, new data centers are expected to create a surge in resource use, raising consumers’ power bills while jeopardizing climate goals. By 2035, the surge in new data centers could send the Interior West’s electricity demand soaring by about 55 percent, WRA warns.

The unprecedented extent of the industry’s energy requirements risks derailing decarbonization goals in several states. Energy experts say the astronomical power needs may keep fossil fuels like coal and gas in use longer. NV Energy, Nevada’s main utility, now expects its carbon emissions to rise 53 percent over 2022 estimates because of new data center growth.

Deborah Kapiloff, a clean energy policy advisor with WRA and an author of the new report, highlights the incredible scale of the additional power needed for the region’s tech infrastructure boom. By her calculations, within the next decade, the West’s planned data centers will burn through enough electricity each year to power 25 cities the size of Las Vegas.

Who covers data center power costs?

In some cases, the industry is outsourcing these energy costs to the public. Kapiloff explains that consumers are likely to shoulder the burden of expensive new power infrastructure, because typically utilities spread construction costs across all users. With the unprecedented demand of power-hungry data centers, that logic breaks down. “When the customer is this large, the old assumption that ‘growth helps everyone’ doesn’t hold,” she said.

In Colorado, regulators are struggling to keep up. John Gavan, a former Colorado Public Utility Commission member, says that utilities in his state may need to roughly double total power production within five years to cope. “The scale here is mind-boggling,” he says. “A single hyperscale data center could consume 10 percent or more of the entire state’s load.”

Officials say that current pricing rules could push higher electricity costs from new data centers onto residential customers. Joseph Pereira, the deputy director at the Colorado Office of the Utility Consumer Advocate, says this may mean rate increases of 30 to 50 percent for households — and those costs could double or even triple in the long term.

Pereira also emphasizes the risks of building new power generation and transmission for data centers that may never be constructed. “If we build the infrastructure and then data center loads don’t show up, somebody is left holding the bag (for the costs),” he says. “Today, that’s existing customers.”

Water on the line

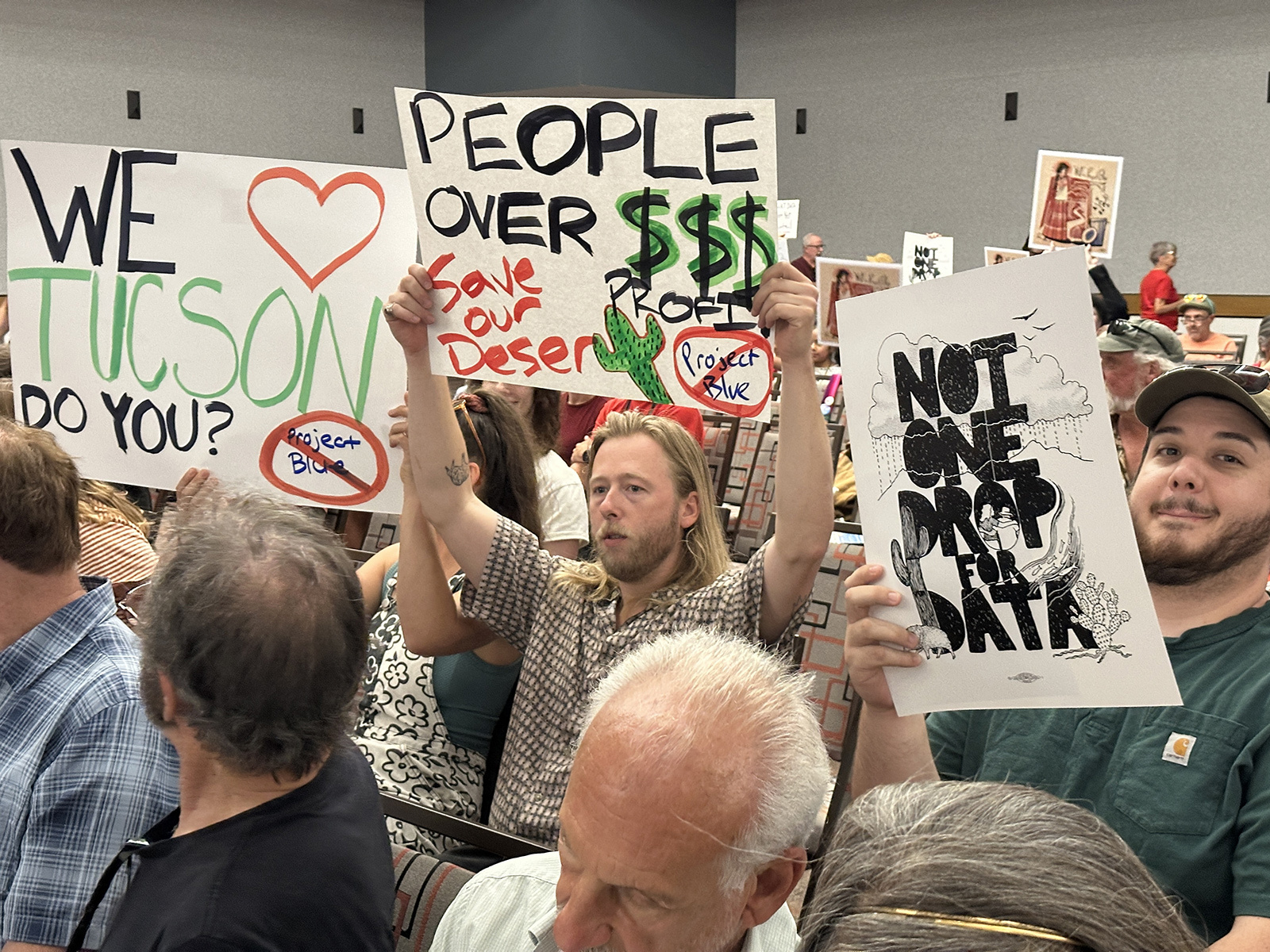

Data centers also bring heavy demands on water. Near Tucson, Arizona, a proposed data center in the Sonoran Desert of Pima County has become a community flashpoint because of the project’s heavy demands in an already water-stressed region. Initial designs suggest the controversial Project Blue will require “millions upon millions of gallons,” says Pima County Supervisor Jennifer Allen, although the official numbers were not disclosed.

“Tricking people out of their water is a clear line that, even in this divided country, people agree on,” said Duke University teacher Allegra Jordan. As a community advocate on data center projects, she’s repeatedly seen local authorities asked to approve developments without key information on their impacts.

In Arizona, community backlash against Project Blue forced a redesign, and the developer now asserts that the new plans will use little or no water, though Allen says she hasn’t seen any documentation to support that assertion. Kapiloff notes that transparency around water use is a common problem. “We have a lack of information about how much total water data centers are using — it’s a big black box,” she says.

Where the potential water needed for new data centers can be estimated, the scale is sobering. In Nevada, for example, currently proposed new data centers will consume an estimated 4.5 billion gallons of water in 2030, if built with conventional cooling. That number rises to 7 billion gallons by 2035 — the equivalent of water for nearly 200,000 people.

Fast-tracked deals, facts under wraps

Yet the speed and secrecy of data center development deals often keep even officials in the dark. During the first phase of Project Blue in Arizona, Pima County Supervisor Jennifer Allen says that she and the rest of the board of supervisors were asked to vote on the proposal without having access to the project’s full information, due to NDAs signed by county staff that extended to elected officials. “Shrouded in secrecy was the game,” she says.

Jordan believes that communities deserve informed consent on the impacts that data centers will have on their power bills, water use, and environmental impacts. “The moral issue is whether or not people should have consent in whether or not their power bills go up, or how their water is being used,” she says.

She also points out that, lured by the promised fiscal gains, local government entities sometimes don’t fully disclose what’s being given away in data center incentives and exemptions. “Often the data center proponents say, ‘this will bring in new property taxes and jobs,’” she says. “But many communities don’t actually understand what they’re giving up. And while the community government is the entity that gets that money, the people paying, in terms of larger electric bills, are everyday citizens.”

Building better: A playbook for responsible development

In response to these mounting pressures, some communities are stepping in with safeguards. After the Project Blue debacle, for example, the Pima County Board of Supervisors implemented new regulatory requirements, including NDA limits and a “sunshine period,” where findings must be made public before votes. Other potential interventions WRA recommends include energy-efficiency requirements, ending tax incentives for data center development, and prioritizing data center projects that commit to renewable power generation.

Consumer advocates like Pereira are also working to ensure that large-load customers pay their own way, helping keep existing customers off the hook if proposed data centers are never built. WRA’s report highlights key tools like specialized rate classes designed to make sure large or unusual customers pay rates that reflect their unique impact, and requirements that data centers pay for their forecasted power needs, even if demand declines or never materializes. Clean transition tariffs, or special electricity rates that help big energy users switch to cleaner energy, could help fund renewable projects to power data centers. Finally, creating standards that keep loads to off-peak hours can help protect both ratepayers and resources.

Energy efficiency best practices and “behind the meter” approaches can help, too. In Europe, innovative models include a cluster of data centers under construction in Finland that will use the heat generated to warm approximately 100,000 homes in Helsinki, and a data center in Norway that provides heated water to support aquaculture nearby. Those techniques can work in the United States too: A new development in San Jose, California is seeking to become one of the most sustainable data centers in the world, embedding energy sources onsite and using waste heat to power equipment chillers.

While tools like these can help, without swift reforms, even the best planning policies won’t prevent the impacts of rapid data center growth. Many communities are facing aggressive data center prospectors and still lack enforceable guardrails and transparent rules that shield ratepayers from costs and protect the environment.

As Kapiloff says, “When you have some of the most highly capitalized corporations in the world building these data centers, does it make sense to have that cost be borne by everyday folks? I think the answer to that is a resounding no.”

Western Resource Advocates is a regional nonprofit fighting climate change and its impacts to sustain the environment, economy, and people of the West. The organization is driving state action to advance policies that create a healthier and more equitable future for all communities. As the go-to experts for more than three decades, WRA’s on-the-ground work deploys clean energy and protects air, land, water, and wildlife.