Effectively managing resilience has never been more important for educators. In the fourth of her five-part series Resilient in the Middle, Julie Schmidt Hasson looks into pausing, pondering and persistence as actions to reframe your effectiveness with students.

By Julie Schmidt Hasson

I collect things, like heart-shaped rocks, glass milk bottles, and vintage encyclopedias. But my favorite collection is my collection of teacher impact stories.

In my early years as a researcher, I interviewed hundreds of people about teachers who made a difference in their lives, trying to understand what teachers said and did to make an impact.

A Reframing Story

You can read about my interviews in this MiddleWeb article. One story in that collection provides a helpful example of reframing, the focus of this article. The story came from a young man named Ethan, who I met on a college campus. Here’s Ethan’s story about his fourth-grade teacher, Mr. Cribbs:

The best thing about fourth grade was getting to go to the upper grades playground, the one with the volleyball net. Every day after lunch, we would organize a volleyball game. Some of us (who happened to be tall and athletic) would dominate every game. We spiked the ball as hard as we could or tried to hit it so the other side couldn’t hit it back. Most of the kids would quit early, and some would get hurt. It started to cause a big conflict at recess.

One day, Mr. Cribbs took the ball. I expected him to terminate our volleyball games. Instead, he bet us fifteen extra minutes of recess that we couldn’t keep the ball going back and forth over the net fifty times. Then he added one stipulation, everyone had to touch the ball at least once. We started to hit the ball so that other kids could hit it back. We started to teach the other kids how to play. We would all count loudly together every time the ball went over the net.

We named it The Infinite Game because we tried to keep it going as long as we could. It became our favorite thing to do at recess, and the whole class played. I began to realize that working together was way more fun than dominating the game.

Now I’m an engineering student. It’s a tough major, and many students drop out. Early in my first class, I organized a study group. We help each other; we make sure everyone succeeds. I could have focused on making the highest grade, but I decided to play The Infinite Game. I’ll be a better engineer for it, and I’m grateful that Mr. Cribbs taught me the value of collaborating.

I marvel at teachers like Mr. Cribbs. He was surely irritated by this recess conflict, but instead of punishing or lecturing the students, he turned it into a teachable moment. Mr. Cribbs had mastered the skill of reframing, a cognitive strategy involving shifting perspectives to view a situation in a new light. When teachers are facing a challenge, reframing enables them to respond constructively, and reframing is a powerful tool for keeping your teacher battery charged.

Reframing for Resilience

In this Resilient in the Middle series, we’ve been exploring what charges and drains our teacher batteries. Reframing helps us turn a problem into an opportunity for impact. In other words, it can turn a potentially depleting situation into a charger. Reframing is more than a psychological concept; it’s a practice that we can learn and transform how we experience our work.

By embracing the practice of reframing, we can navigate challenges with greater ease, foster a more positive mindset, and build resilience that benefits both us and our students. We always have the power to change our perspective – and in doing so, we can change how we view our teaching.

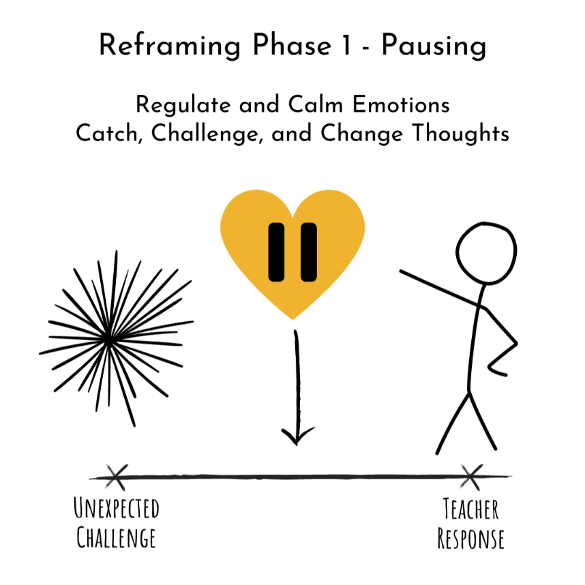

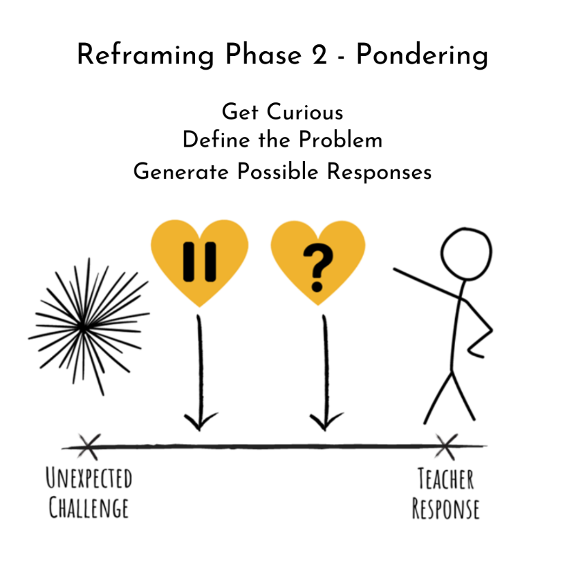

There are three main phases in the practice of reframing: pausing, pondering, and persisting.

1. Pausing

When unexpected challenges come, they often elicit some unhelpful thoughts and emotions. In the second article of this series, we explored regulating emotions. It’s difficult to make good decisions or employ creative problem solving when dysregulated. Taking a few deep breaths and a moment to relax your body can help you return to calm.

Psychologist and neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett developed the constructed emotions theory, which suggests that our emotions don’t simply happen to us. Instead, they are constructed in our minds to explain what is happening in and around us. When our hearts start racing and our palms start sweating, our brains need to figure out why.

Dr. Barrett uses the example of a bad stomach ache. If we know we’ve eaten a big meal, we’ll attribute our body’s signals to that event and reach for an antacid. However, if we experience a bad stomach ache after a big argument with a spouse, we might reach for our therapist’s number instead.

Our brains are always searching for explanations and meaning. Emotions don’t dictate our actions, but the meaning we construct informs what we do next. That’s why, after calming, the next step in the pause is examining our thoughts.

The Catch, Check, Challenge, Change practice is a simple and effective cognitive tool for managing unhelpful or negative thoughts (it works for students and teachers). It is rooted in cognitive-behavioral principles and can help teachers recognize, evaluate, and reframe unhelpful thoughts.

First, become aware of what you are thinking. For example, I wonder if Mr. Cribbs initially thought, These kids never get along. Or perhaps he thought, I can’t ever get a minute of peace.

Absolutes like never and ever are often clues that you should take the next step and question the validity of a thought. You can question whether what you’re thinking is worse than the situation actually is. You can question whether you have any evidence contrary to the thought.

Once you’ve challenged a thought and determined it to be invalid and unhelpful, you can change it. Is there another way to look at the situation or challenge? You can always create and choose more empowering thoughts. Catching, challenging, and changing your thoughts isn’t easy, but it’s necessary for reframing. And holding onto unhelpful, untrue thoughts can be a big battery drain.

2. Pondering

The next phase of reframing is pondering. When an unexpected challenge happens, especially when it’s connected to a student’s choice, we may quickly construct an explanation. But assumptions can be unhelpful, and no one likes incorrect assumptions about their actions or intentions.

It’s easy to create a narrative or fill in the blanks of someone else’s story. Seeking to understand the experiences of another through genuine curiosity and care takes more time, but it pays off in stronger relationships and better outcomes.

Authors Edgar and Peter Shein advocate for a practice called humble inquiry, which is the art of asking questions with genuine curiosity and interest in another person. It’s a commitment to acknowledging what we don’t know and our need for more information.

Humble inquiry is a necessary practice for teachers. Making decisions based on assumptions about students’ needs is unreliable. After all, decisions are only as good as the information on which they are based. When it comes to reframing, curiosity is more helpful than judgment.

Engineers may be our best models for reframing problems, as their work is centered on solving complex problems. They start by defining the problem to ensure they are solving the right issue, and they always consider the whole system or the bigger picture. Then they consider the problem from other perspectives.

As teachers, it’s always helpful to think about challenges from a student’s perspective. Engineers brainstorm a litany of possible solutions and think about the potential outcomes. We can do that, too. When it comes to classroom challenges, we are always experimenting. Pondering in this way helps us keep from getting stuck. And when it comes to our batteries, curiosity is much more energizing than frustration or judgment.

3. Persisting

Persisting is the last component of reframing. Persistence allows us to push through obstacles, setbacks, or initial failures, which are often part of the process. Sticking with a challenge encourages exploration of different strategies and solutions, and it often leads to thinking outside the box, uncovering innovative approaches that might not surface initially.

Ethan’s story about Mr. Cribbs is part of a teaching highlight reel. Certainly, there were times when Mr. Cribbs’ attempts at turning challenges into opportunities for impact were not so successful.

Teaching is full of experimentation, trial and error. Those less successful times can be opportunities for our own growth, if we are willing to reflect. That’s why reflection is the topic of our next article in this series. As you persist in reframing challenges, give yourself some grace. Curiosity and a sense of playfulness in the process can help you stay longer, grow stronger, and keep making an impact.

Dr. Julie Schmidt Hasson is a professor in School Administration at Appalachian State University in Boone, NC. A former teacher and principal, she now teaches graduate courses in school leadership and conducts qualitative research in schools. She also works with schools and districts to increase teacher resilience and retention.

Dr. Julie Schmidt Hasson is a professor in School Administration at Appalachian State University in Boone, NC. A former teacher and principal, she now teaches graduate courses in school leadership and conducts qualitative research in schools. She also works with schools and districts to increase teacher resilience and retention.

Julie studied to become a Certified Resilience Trainer under the guidance of Dr. Amit Sood. She shares the impact resilience can have on educators in her book, Pause, Ponder, and Persist in the Classroom: How Teachers Turn Challenges into Opportunities for Impact, at her website Teacher Recharge, and in her five-part MiddleWeb series.

To learn more about Julie’s research on long-term teacher impact see Lessons that Last: 185 Reflections on the Life-Shaping Power of a Teacher (Routledge/Eye On Education, 2024). Read our excerpt. Follow her on Bluesky, X-Twitter and Instagram. She is also the co-host of the Lessons That Last podcast.