Regularly, we feature a Global Roundtable in which a group of people respond to a specific question in The Nature of Cities.

Introduction

Manifesting “Urban Natures” into New Imaginings and Becomings

This discourse took a distinctly political turn: reclaiming cities as spaces of multispecies justice and commoning. Participants articulated principles for a more-than-human city where justice, care, and interdependence define urban politics.

Visualizations of future cities are often filled with green streets and roofs, lush facades and balconies abounding with greenery. In policy and practice, concepts such as ecosystem services and nature-based solutions gain traction. While these are welcome additions that take other-than-humans into account, they do remain examples of anthropocentric and utilitarian ideas about nature being there to serve humans.

The book, “Urban Natures: Living the More-than-Human City” (Berghahn, 2023), takes a different stance―it argues that cities need to recognise the agencies and rights of nonhuman natures. By taking a more-than-human approach, we acknowledge the relational ties and deep cultural connections between humans and nonhumans, to reconsider these relationships and shift towards more just, sustainable, and convivial multispecies cities. This book emerges from a series of events and ideas (see Preface), to bring together diverse perspectives from cities around the world that explore how people are making visible, are reconnecting with, and are recognising the political framings of, urban natures.

Indeed, we argue that the more-than-human city is already here, beckoning the questions: what can we learn from this insight? How we can live, design and govern more-than-human cities, in ways that recognise relationships and interdependencies, and that challenge the ideas and images that currently dominate about cities and city futures? Such tactics include recentering human-nature relations, where several chapters emphasise the role of reconnection through performativity―such as by “thinking with”, “becoming with” and “designing with” (see Introduction chapter by Edwards et al. 2023), be it through walking and listening, composting or co-designing, drawing on ethnographic studies and creative, arts-based practices. Others focus on enactment by highlighting the possibilities and potentials for connection and care, but also the politics involved, for example as Aboriginal agricultural practices are reimagined and revitalized in colonialized cityscapes (Chen, 2023). Here ethical questions are raised that demonstrate the more troublesome sides of such relations, for example when urban gardeners play with, feed and give urban foxes medicine (van Duppen, 2023), or when care for native nature is enacted in practices of weeding (Fischer, 2023).

Rather than seeing the publication of the book as the end of the journey, we have sought to continue to introduce these themes to broader audiences for their reflection and contribution towards new imaginings, becoming, and manifestations. For example, at the POLLEN conference in Lund (Sweden) 2024, participants of the Urban Natures: Living the More-Than-Human City Book Launch didn’t just attend another academic discussion—they collectively contributed to imagining a radical vision for the future of cities. The attendees co-created a “Manifesto for the more-than-human city” which completed a previous draft elaborated by the participants of the TNOC dedicated panel. This process revealed the challenges of recognizing non-human agencies, but also the critical necessity of shifting away from human-dominant, extractive urban practices. This discourse took a distinctly political turn: reclaiming cities as spaces of multispecies justice and commoning. Participants articulated principles for a more-than-human city where justice, care, and interdependence define urban politics. They claimed equitable access to green-blue spaces for all humans and non-humans, the recognition of marginalized urban natures and their histories of erasure; a moral gaze that includes non-human beings as political subjects.

Slowing down and engaging with the urban ecosystem at multiple scales—through senses, time, and creative practices—are ways to dismantle anthropocentric hierarchies and move towards care-full urbanism. Moreover, participants pointed to the need of reclaiming urban spaces not for growth, but for thriving—human and non-human alike: envisioning post-growth cities means stopping the bulldozers that displace life and rejecting the urban-rural divide. Instead, participants imagined cities that celebrate justice, build alliances with non-humans, and center marginalized communities in decision-making. As the event concluded, it was clear that this collective vision transcends academia. It is a call to action—an urgent response to the climate crisis, biodiversity loss, and rising inequalities. In imagining the more-than-human city, POLLEN participants redefined urban politics, offering us a path toward justice for all life.

The Nature of Cities (TNOC) has also played an important role in carrying this work along – in its pre-production, where Edwards, Hahs, and Hwang organised a panel exploring typologies of urban nature through the lenses of “stray, care and wild”, through to virtual workshops on “Urban Natures: Making Visible, (Re)Connecting and (Re)Politicising” held during the book production that brought contributors together to present and discuss its many overlapping themes; through to post-production, where walks and workshops (see the post by Qualmann below) were held once again to showcase the book’s outcomes and insights. This TNOC Virtual Roundtable serves as another outpost that’s been opened to participants from TNOC events and a wider global audience to explore what the sensorial experiences of a more-than-human city could look like.

References:

Chen, D. (2023). Relational Growing: Reimagining Contemporary Aboriginal Agriculture in Colonialized Cityscapes. In: Edwards, F., Popartan, L.A., & Pettersen, I.N. (Eds.). Urban Natures: Living the More-than-Human City (pp. 164-178). Berghahn Books.

van Duppen, J. (2023). Caring for Foxes at a London Allotment: Tales from a Contested Interspecies Playground. In: Edwards, F., Popartan, L.A., & Pettersen, I.N. (Eds.). Urban Natures: Living the More-than-Human City (pp. 150-163). Berghahn Books.

Edwards, F., Popartan, L.A., & Pettersen, I.N. (2023). Introduction. Mapping the More-than-Human City in Theory, Methods and Practice. In: Edwards, F., Popartan, L.A., & Pettersen, I.N. (Eds.). Urban Natures: Living the More-than-Human City (pp. 1-30). Berghahn Books.

Fischer, J.-M. (2023). ‘War on Weeds’: On Fighting and Caring for Native Nature in Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand. In: Edwards, F., Popartan, L.A., & Pettersen, I.N. (Eds.). Urban Natures: Living the More-than-Human City (pp. 179-193). Berghahn Books.

About the Writer:

Ferne Edwards

Ferne Edwards has conducted research on sustainable cities, food systems and nature across Australia, Venezuela, Ireland, Spain, Norway and the UK. Her books include, ‘Urban Natures: Living the More-than-Human City’ (Berghahn 2023), ‘Food for Degrowth: Perspectives and Practices’ (Routledge, 2021), and ‘Food, Senses and the City’ (Routledge, 2021). She works at the Centre for Food Policy, City St. George’s, University of London.

About the Writer:

Ida Nilstad Pettersen

Ida Nilstad Pettersen is a professor at the Department of Design, Faculty of Architecture and Design, NTNU–Norwegian University of Science and Technology. She leads the department’s strategic area Design for Sustainability, and does research that addresses sustainability transitions, practice transformation, participation, consumption, and nature relations. She is co-editor of the book ‘Urban Natures: Living the More-than-Human City’.

About the Writer:

Lucia Alexandra Popartan

Lucia Alexandra Popartan has a background in Political Science and a PhD in Water Science and Technology. She is a postdoc at LEQUIA, an environmental science group from the Universitat de Girona, where she co-coordinates the Socio-natural Systems research line. Her research interests include water remunicipalisation, urban political ecology, populism, social movements, edible cities. She is co-editor of the book “Urban Natures: Living the More-than-Human City” (Berghahn Books).

Lily Fillwalk

The Right to the More-the-human City

These dreams are not set in stone, and we, as scientists, must work with and in our communities to imagine what a more-than-human city can be. How beautiful might the unknown be?

To develop a vision of the more-than-human city, we must share an understanding of what the human city is and for whom it exists. The geographer David Harvey understands cities as fundamentally capitalist spaces―they centralize populations to enable value creation and, in the process, dispossess “the urban masses of any right to the city whatsoever” (Harvey 2012, p. 22). The “right to the city”, a concept developed by both Harvey and French philosopher Henri Lefebvre, is a fundamental reimagination of what it means to live in a city. Lefebvre asserts it is “nothing less than a revolutionary concept of citizenship”, while Harvey envisions it as “the freedom to make and remake ourselves and our cities” (Lefebvre, 2014, p. 205; Harvey, 2015, p. 314; Monte-Mór & Limonad, 2023). While Harvey and Lefebvre do not mention non-humans directly, one could apply this framework to nature. The first step to imagining a more-than-human city is foregrounding the needs of citizens, regardless of species. Living in an urban area must include the right to place-making, allowing residents to shape their local natures.

If the city were organized and centered on the well-being of its inhabitants, what we know as the urban landscape might look ecologically different, prioritizing human well-being and ecosystem services. When considering the placement of nature in the city, we should ask ourselves if we are inspired by a past sense of what nature in the region was or if we are looking forward to a future integration of what the natural environment in the city could be (Monte-Mór & Limonad, 2023). Suppose we hope the city transforms into a more natural space centered around environmental justice principles. In that case, we must move past the capitalist frameworks in which the city was envisioned and utilize a more decolonial lens moving forward with the greening of the urban landscape (Monte-Mór & Limonad, 2023). Urban ecology is crucial to realizing more diverse urban natures.

Urban ecology is an interdisciplinary field centered on understanding human and non-human interactions in urban areas, especially regarding the built environment (Pickett & Cadenasso, 2012). Scholars suggest that ecosystem services are not gained directly from the implementation or existence of nature in cities but rather from the interaction of citizens and nature, which co-produce benefits (Andersson et al., 2014; McPhearson et al., 2016). Scholars in the field also suggest that ecology should be in, of, and for cities (Pickett et al., 2016; McPhearson et al., 2016). A utopian vision of the more-than-human city requires the concerted engagement, organization, and mobilization of citizens who can dream and construct a future in which urban natural environments emerge as central to the well-being of its populace. An effort that prioritizes place-making and subsequent place-keeping will help humans to coexist symbiotically with nature toward a healthier and whole humanity. These dreams are not set in stone, and we, as scientists, must work with and in our communities to imagine what a more-than-human city can be. How beautiful might the unknown be?

About the Writer:

Lily Fillwalk

Lily Fillwalk is currently a Doctoral student in Ecology & Evolution at Rutgers University. Fillwalk’s research interests lie at the intersection of urban ecology, socio-ecological interactions, and soil science. Fillwalk holds a Master in Environmental Science from Yale University, and a Bachelor of Arts in Environmental Science from Pitzer College.

Audax M. Gawler

North Nest Resident Guide (Human Edition)

If you still need to do so, please upload your Multispecies Citizen Agreement to the Narrm Municipal database to confirm your stewardship commitment.

Welcome to The North Nest! As a human resident of this interspecies community, you’re part of an innovative architectural project creating safe and harmonious neighbourhoods that reflect the diverse multispecies community of our city. Whether this is your first interspecies abode or you’re a seasoned multispecies neighbour, please take a moment to explore this welcome package, designed to acquaint you with the onsite ecosystem, reciprocity commitments, and seasonally updated resident directories.

(This package is intended for human residents only and uses language accordingly. Multispecies editions are available via pheromone markers, colour-coded guides, vibration, or relational choreography best suited to the mollusc, avian, reptile, mammal, vegetal, and fungal residents.)

Building Overview

In alignment with City as Forest Principals, The North Nest is designed to support diverse life forms. Human units occupy the inner building layers, while outer walls offer designated entrances and habitats for other residents, including mammals, reptiles, birds, and insects. Kindly respect these routes as they are reserved for the wellbeing of our multi-legged, feathered, and scaled neighbours. These entrances are strictly off-limits to human residents regardless of convenience or accessibility, and human Abode Stewardship Agreements do not extend to outer walls and interspecies infrastructure.

Who lives here?

Our resident population changes with the seasons, and up-to-date interspecies resident directories can be found at communication nodes on each floor. Depending on your apartment location, you may encounter a range of other residents, with amenities provided for a vast array of residents, including frogs, snakes, possums, raptors, sugar gliders, cicadas, yabbies, spiders, dragonflies, and many others. Direct interaction with other species should be limited outside structured programs to ensure maximum well-being for creaturely residents. Social and cultural primers, alongside Therolinguitic translation resources, can be found within all resident directories, and our team of Multispecies Communication Officers are available in communal gathering points every Thursday to help you with interspecies etiquette.

Resident Engagement & Environmental Stewardship

The Nest is a self-contained ecosystem, with air filtration sustained by each floor’s vegetation and enhanced by the human-free grassland on level 4 and rainforest on level 9. Water purification is managed by basement and ground floor wetlands, while our onsite regeneration system transforms waste into compost for shared food gardens. Aligned with National Stewardship and Reciprocity Standards, residents are invited to actively support these systems by joining the groups that manage these spaces or even caring for the human-free grasslands on level 4, rainforest on level 9, or the basement wetland. A range of species subgroups can also be joined if you are inclined to work closely with your neighbours, with activities rotating across the seven-season calendar. The Moss Matt and Hive healing spaces are also currently seeking human facilitators for weekly sessions.

Community upkeep

Each apartment and floor in the Nest are unique, with different multispecies neighbours to consider. As you settle in, keep an eye out for your companions and their needs. You may encounter insect hotels, pollinator-safe lighting, water microhabitats, web zones for arachnids, no-tread fungal areas, avian nesting platforms, and collision-safe lighting to support calm fly-zones, or even see the busy paws and claws travelling across the buildings wildlife corridors which connect us and our neighbors to the city Sanctuary Zones. Upper-level residents are encouraged to maintain feeder and nesting material boxes on their balconies, while ground-floor residents can find instructions in their interlink for supporting reptile corridors and nesting areas built into balcony edges.

Please Note: In support of Migratory Moths, next week will be our second annual blackout event, followed by reduced-light nights to support nocturnal mammals and human sky-gazing practices. Please adhere to low-light guidelines during this period, including complete blackout on designated days. The basement remains closed for aquatic recreation until the flood season ends. Alternative aquatic access is available on the ground and in mid-level wetland regions, and fishing is currently permitted for trout and eels. If you still need to do so, please upload your Multispecies Citizen Agreement to the Narrm Municipal database to confirm your stewardship commitment.

About the Writer:

Luna Mrozik Gawler

Luna Mrozik Gawler is an interspecies futures artist, working to advance visions of ethical, equitable and exuberant planetary futures. As a multigenre Symbiopunk, Luna practices outside of disciplines with the intent to disrupt and refigure anthropocentric paradigms by repopulating the social imaginary with multispecies companions, comrades, and co-creators.

İdil Gaziulusoy and Gloria Lauterbach

More-than-Human Flourishing in the Darker Urban: A vision vignette

A more-than-human city is a place of exploration, reflection, dialogue, reciprocity, and care.

Light pollution caused by urban areas is a significant problem for astronomical research. In addition, excessive use of artificial light has impacts on climate change due to energy consumed and by reducing the capacity of forests to sequester atmospheric carbon. Beyond these impacts, light pollution also influences the well-being of human and non-human animals, plants, and ecosystems negatively by disrupting physiological processes of rest, reproduction, feeding, photosynthesis, seasonal migrations, and so on. Also, last but not least, losing dark skies in urban areas adds to the loss of human-nature connection which has significant cultural and psychological implications. Humans’ desire and dependence on artificial light conflict with the goal of achieving futures in which both humans and ecosystems flourish. However, it is not possible to completely get rid of artificial light as it is needed for human safety and the continuation of certain human activities during nighttime. We must rethink our relationship with and dependence on artificial light through a lens of more-than-human flourishing and transform our cities in alignment. Here we present a vision vignette of how this could look and feel like.

A more-than-human city is where the rhythms of natural light are respected, and artificial light is minimised to levels of absolute necessity. Cities do not advertise themselves as “The City of Light” but as “The Dark City”; the beauty of a city in the nighttime is not measured by how much light it emits from its buildings but by how the city looks under the full moon or the starred light during the new moon. Paths in urban green areas are lit by soft, bioluminescent, organic lights which have become part of the ecosystems as the specific species are chosen based on thorough research regarding their local compatibility. Streetlights emit focused beams when needed triggered by motion sensors. In less dense neighborhoods, personal lights are carried by individuals, and fixed light infrastructure is a thing of the past. Where possible, trees and other canopies are placed on the streets as light shields while also keeping the urban heat island effect under control in hot climates during the summer months. The large open-air events take place in venues with light shields and under strict regulations of how much and for how long they can be lit. Nordic cities with long dark seasons have re-cultivated practices of rest during wintertime for their human and more-than-human inhabitants. Adjusted lighting, indoors and outdoors, during the dark season supports living with the circadian rhythm rather than against it. Simultaneously, soothing narrations of human and more-than-human cohabitation sprout from these seasonal islands of rest.

As more-than-human cities become darker around the year, perception changes: while the eyes can rest during the evenings, other senses gain back their strength. Citizens become more and more aware of all levels of urban pollution and begin to caringly look out for improving their own health as well as that of other/s. A more-than-human city is a place of exploration, reflection, dialogue, reciprocity, and care. Urban darkness bit by bit matures into a phenomenon with the distinct quality of generating resilience to environments and their inhabitants as well as new inspiration for a new genre of design: designing with/for darkness.

Note:

We are not the first ones to imagine a dark city or study the relationship between darkness and urban design. This vision vignette has been inspired by the pioneering works of many thinkers as well as our conversations with experts from lighting design, urban ecology, environmental psychology, and human physiology who have been our consortium partners in the NorDark project, a Norforsk-funded project aiming to develop interdisciplinary knowledge to mediate needs of wildlife and human needs during the long Nordic dark season in urban green areas. For interested readers, we recommend the following edited book: Dunn, N., & Edensor, T. (Eds.). (2024). Dark Skies: Places, Practices, Communities. Routledge.

About the Writer:

İdil Gaziulusoy

İdil Gaziulusoy is a design researcher with a PhD in sustainability science. She leads NODUS Sustainable Design Research Group in Aalto University, Finland. She is interested in the new ways of designing and the agencies enabled, enacted and embodied by design that emerge in transformations/transitions contexts. More-than-human considerations in urban transformations is among her current research focus areas.

About the Writer:

Gloria Lauterbach

Gloria Lauterbach is a postdoctoral researcher in NODUS Sustainable Design Research Group, Aalto University (Finland). Through her artistic research Gloria aims to better understand and to make better understandable topics around material cooperation, dialogical post-humanism, more-than-human-centric methodologies, modes of habitation, post-disaster futures and urban wilderness.

Giulia Gualtieri

Designing with Nature: Co-creating urban spaces for all

The more-than-human city is not merely a vision for the future but a critical paradigm for building sustainable and inclusive environments where all living entities can thrive.

The more-than-human city, as I envision it, is a dynamic and evolving space where humans and non-human life collaborate to shape urban environments that support mutual growth and thriving ecosystems. My research explores how Participatory Nature-Centered Design (PND) can inform this vision by rethinking the way we approach urban spaces and fostering a mindset that acknowledges all living entities as central actors in the design process. This mindset moves beyond anthropocentric frameworks, embracing the interconnectedness and interdependence of human and non-human lives within urban environments.

One of the projects that has informed my work is the Eco-Cathedral in Heerenveen, Netherlands. Conceived by Louis Le Roy and managed by Stichting Tijd, the Eco-Cathedral is an evolving, open-ended experiment in collaboration between humans and nature. At its core is a simple but profound process: humans stack surplus construction materials into porous structures, which nature gradually inhabits and transforms over time. Observing the Eco-Cathedral reveals how biodiversity flourishes when design integrates porosity and variation in scale, principles that are vital for fostering life. Microhabitats within the brick structures shelter smaller species, while larger fauna and diverse plant life coexist in the broader landscape.

The Eco-Cathedral also highlights the importance of long-term thinking and adaptability in urban design. During interviews with Peter Wouda, representatives of Stichting Tijd, I learned about the value of patience and humility when working with nature. Unlike traditional urban projects that prioritize immediate results and rigid control, the Eco-Cathedral evolves over decades, aligning with the rhythms of nature. It demonstrates how a flexible approach can empower both human and non-human participants, fostering spaces that evolve with ecological and seasonal changes.

These insights, combined with theoretical studies, have informed the development of the Participatory Nature-Centered Design principles. Designed to help urban practitioners shift from anthropocentric design practices to more nature-inclusive approaches, these principles aim to foster harmonious coexistence among diverse forms of life:

- Commit to a fundamental mindset shift that redefines the relationship between humans and nature, placing nature (or (all) living entities?) as central actors and intrinsic beneficiaries in urban design processes.

- Recognize nature as a multi-species collective, where all living entities, including humans, are interconnected, in synergy, and interdependent within their ecological systems.

- Acknowledge the spirit in all living things, emphasizing their needs and efforts to maintain themselves and realize their inherent potential.

- Nurture, steward, and care for diverse species and ecological environments with humility, treating nature as a subject rather than an object.

- Empower natural and human actors in design processes by giving voice and space to act, while addressing conflicts (such as those posed by invasive species).

- Embrace openness, flexibility, and adaptability in design methods, approaches, and tools to respond to evolving ecological dynamics, shifting circumstances, and urban ecological contexts.

- Create spaces that evolve with ecological rhythms, where seasonal and long-term changes are embraced to ensure sustainable coexistence between nature and humans all living entities.

- Design urban environments for positive biodiversity outcomes, advocating for the rights of nature, and emphasizing a commitment to healthy and thriving ecosystems.

By embedding these principles into urban planning and design, we can take a meaningful step toward creating cities that celebrate the diversity and vitality of life. The more-than-human city is not merely a vision for the future but a critical paradigm for building sustainable and inclusive environments where all living entities can thrive.

About the Writer:

Giulia Gualtieri

Giulia Gualtieri is a researcher at Hogeschool Windesheim Almere and a PhD candidate at TU Eindhoven. Her work investigates how Participatory Nature-Centered Design (PND) can integrate agency of non-human inhabitants into urban design processes, fostering urban biodiversity and coexistence in cities.

Saba Mirzahosseini

From Pardis to Paradise: Ancient wisdom from Persian gardens

The wisdom of Persian gardens shows us that the path to sustainable urban futures lies not in conquering nature, but in remembering our place within it.

Nature speaks through the ages, from the ancient paradises of Persia to the green cities of tomorrow. In the heart of every Persian garden lies a profound truth: nature transcends its physical form to become a bridge between the earthly and the divine. As we reimagine our cities for the future, these ancient sanctuaries offer timeless wisdom about harmonious coexistence. The garden, or “pardis”, has always been more than a carefully cultivated space―it is a living poem, a meditation on the sacred relationship between all beings. Saadi Shirazi, the revered 13th-century Persian poet, captured this essence in his masterwork “Gulistan”, where he writes that a single flower holds more wisdom than volumes of books. In his book “garden”, every rustling leaf whispers ancient knowledge, every flowing stream sings songs of unity, and every blooming rose reveals the face of the divine. This is not mere poetic metaphor, but a deep understanding of nature’s role in awakening human consciousness.

Today’s cities desperately need this wisdom. As an environmental engineer, I have witnessed how our modern urban spaces often reduce nature to its utilitarian functions. We calculate the carbon sequestration of trees, measure the cooling effect of green spaces, and quantify ecosystem services. While these aspects are important, they miss the profound spiritual and psychological dimensions that make nature essential to human flourishing. The Persian garden tradition teaches us that true sustainability emerges from a relationship of reverence, not dominance. In these gardens, geometric precision meets wild beauty, human design embraces natural chaos, and practical innovation serves spiritual elevation. The ancient qanat irrigation systems, for instance, were not just technological solutions but represented the sacred flow of life itself.

Each element in a Persian garden plays multiple roles in this grand symphony of existence. The cypress trees stand as sentinels of permanence, teaching patience and perseverance. The nightingales remind us that nature’s voice carries both joy and melancholy. The roses demonstrate that beauty and resilience can coexist. Water, flowing through carefully designed channels, symbolizes the journey of the soul while nourishing the soil. Our more-than-human cities must rediscover this multidimensional approach to nature. We need urban spaces that not only support biodiversity and climate resilience but also nourish the human spirit. Places where children can learn the language of birds, where elders can find solace in the shade of ancient trees, where communities can gather to celebrate the eternal cycle of seasons.

The wisdom of Persian gardens shows us that the path to sustainable urban futures lies not in conquering nature, but in remembering our place within it. When we design cities with this understanding, we create spaces that honor both the visible and invisible connections that bind all living beings in an eternal dance of mutual becoming.

About the Writer:

Saba Mirzahosseini

Saba Mirzahosseini is a PhD researcher at Politecnico di Torino and Links Foundation who specializes in urban sustainability and Nature-based Solutions. She combines engineering expertise with data analytics to develop tools that bridge the gap between policymakers and citizens for Nature-based solutions Planning and Monitoring. Her notable work includes leading social impact analysis for EU projects.

Clare Qualmann

A Tour of Diverse Urban Natures in Berlin

The combined expertise of our participants and the leaders of the walk brought into discussion the politics and power relations in the scenes we moved through opening not just our eyes, but all our senses to Berlin’s specific more-than-human constituents.

At the Nature of Cities festival in Berlin, in June 2024, Ferne Edwards, Ida Nilstad Pettersen, and Clare Qualmann led a walk titled “A Tour of Diverse Urban Natures in Berlin”, inspired by and responding to themes in the book “Urban Natures: Living the More than Human City”. The book is an edited collection drawing together diverse perspectives following three key themes: Making visible, (Re) connecting, and Politicizing Urban Natures and the walk touched on each of these, prompting discussion between hosts and participants about the relationships, politics, and possibilities for human/more-than-human co-existence in cities

None of us are based in Berlin, so our task to devise a walk was initially carried out remotely, pouring over maps, street view, and satellite images to try and decipher the places and spaces that we were seeking. What were we looking for? What does the more-than-human city look like? From an aerial viewpoint, we began with patches of green; parks, gardens, and cemeteries – locations that we knew could be plentiful with plants, animals, “wildlife”.

Once-on-the ground, in the days before the festival, we walked and wandered following the leads of our remote preview to pin down a route that resonated with our research and built a narrative in its pathway through the city. We moved through apartment block gardens to motorway flyovers, urban meadows to canalside cuttings, cemeteries, and the ubiquitous Berlin kleingartens, with tree-pits, road-side verges, and ‘waste’ ground to guide us in between.

Along the edge of a grassy field, a gap in the fence made a way for us to access steep steps down to the canal, the steps slippery with a build-up of leaf mulch, and moss. The air smelt damp and full of life. Although the water is contained in a rigid concrete channel, its banks burst with life; wild plums and elder, roses and other climbing plants hang over the edges. We heard birdsong and the buzzing of insects. A noisy motorboat passing below made waves that splashed on the walls of the canal. Through the bushes, we glimpse a makeshift shelter, a tent and tarpaulin.

Further on a cemetery, full of tall trees and shady grassed areas, small compost heaps discretely tucked out of sight. The water barrels dotted near the paths all have small wooden ladders, escape routes for unfortunate creatures who might get trapped. In the furthest corner of the graveyard, a pet cemetery with intricate memorials, photographs, and floral tributes speaks to the bonds of human-pet relations.

Across another road we arrive at a kleingartencolonie, small plots of growing space leased by families, many with little houses for occasional occupation (you are not meant to live in them). Outlined by thick hedgerows, some neatly trimmed and others slightly wilder, each plot has its own character, though most look very well groomed. Some have fruit trees, grassy lawns, and play equipment, others have flower beds, and vegetable patches. Notably, most had plastic sacks of compostable material left at the gate for municipal collection.

These three vignettes are just snippets from our walk, only 2.5km long, but packed with diverse encounters with the more-than-human-city. From the illicit dwelling next to the canal, where humans were finding space to live outside of the usual bounds of urban permissivity, to the carefully maintained grounds of the cemetery where human remains return to the earth, from the domestic relationships of pet animals and their humans to the rule-bound garden cultures of the Kolonie, perennially threatened by rising land values, the combined expertise of our participants and the leaders of the walk brought into discussion the politics and power relations in the scenes we moved through opening not just our eyes, but all our senses to Berlin’s specific more-than-human constituents.

About the Writer:

Clare Qualmann

Clare Qualmann is an artist/researcher whose work focuses on socially engaged, site specific, and experimental modes of contemporary creative practice, often using walking. She is Associate Professor at The University of East London where her teaching and research explore the interconnections between art, activism and the radical potentials of participation. Clare Qualmann was a contributing author to the book, Urban Natures: Living the More-than-Human City, edited by Ferne Edwards, Lucia Alexandra Popartan and Ida Nilstad Pettersen, was published by Berghahn in 2023, and co-deviser of the ‘Tour of Diverse Urban Natures in Berlin’.

Aylin Yildirim Tschoepe

What does the more-than-human city look like? Culinary Commoning: Multisensory delicacies as care-full knowledge production toward more-than-human collective urban futures

Culinary commoning is collective action and care for a more-than-human community, which includes humans, plants, and various interior and exterior organisms.

How we want to live and envision social and spatial futures is negotiated in cities. Equal rights to expression and access to urban commons are constantly struggled over and shift over temporal, spatial, and technological transformations. The city is inscribed with and congeals power structures, and acts also as a distributor of access and resources between humans and other species and organisms.

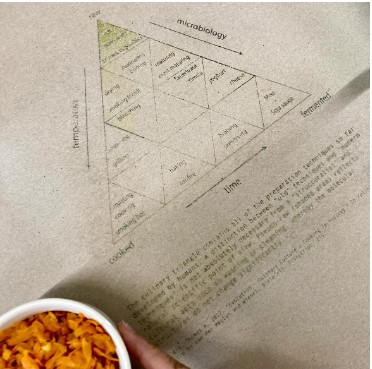

A more-than-human-city is one where human actors understand themselves as entangled in larger ecological systems, in which they coexist with and are co-dependent on other living beings in the rhythms of life. One of the key resources in such cycles is food, and in a sustainable, circular approach to it, urban nature plays a vital role in the more-than-human city. Such an understanding of the more-than-human city is negotiated and shared during encounters in a community of practice in science with public events hosted through metaLAB (at) Basel’s “soul kitchen”. With a changing group of participants, we engage in multisensory experiences as we approach cookery, food, and nutrition through the understanding of coexistence and mutual care as we explore and learn together about low-cost urbanity and economies of sharing. This opens a path to depart from extractive urban practices toward commoning and care for a more-than-human city, as we collect wild herbs, plants, and saved food. We ferment and prepare food with and for each other while being mindful of edible resources and caring for their cycles and growth as well.

“Multisensory delicacies”, for example, are a series of events, in which the more-than-human city takes a shape through interweaving multiple stories that emerge from collected edibles and human collaborations as care-full knowledge production toward collective urban futures. The multisensory delicacies events bring together an interested public as well as peers and students from various disciplines, with the task to collect edible food: leftovers at home, from food saving initiatives, as well as herbs and vegetables that grow in the city and plant beds on campus. Depending on what we bring to the table collectively, groups form spontaneously and begin to assemble “everyday hors d’oeuvre” (small bites to share with everyone): each bite has a story to tell about its place in the city and the overall structure of taste between homes, city, and urban natures.

In a similar preparation and process, we introduce fermenting as a cultural practice across time and various urban areas. Together, we experience through shared culinary practice that, through fermentation, collected food is saved and its edibility extended while learning about the interrelations between human and planetary health in a performance lecture format that shows the process of taking care of other organisms during various fermentation processes such as feeding sourdough.

These collective experiences and performative formats are one of the many entry points

to understanding, caring for, and envisioning what a more-than-human city looks like.

Culinary commoning, therefore, is collective action and care for a more-than-human

community, which includes humans, plants, and various interior and exterior organisms.

Culinary commoning is also a set of practices toward creating and sharing experiences

and knowledge regarding food saving and circular processes, engaging together in a

reflected approach when using and managing resources in urban foodscapes that

surround us humans as elements of an urban ecosystem.

Important note:

“soul kitchen” is a transdisciplinary format of exchange that questions the boundaries

between institutionalized and embodied forms of knowledge, practices, and aesthetics.

It takes inspiration from the rich history and critical discourse regarding feminist

practices around food (Krasny 2020), building onto a culinary turn in design (van der

Meulen & Wiesel 2017), and references precedents and related communities,

collectives and projects that add richness and contribute to the relevance of

commoning approaches and collective visions.

About the Writer:

Aylin Yildirim Tschoepe

Aylin has a PhD in Anthropology, Doctor of Design and is professor of Design Anthropology at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland FHNW. As head of metaLAB (at) Basel and head of research at ICDP, Aylin fosters collaborative research in design, technology, life sciences, and social sciences. Studying the intersections of bodies, spaces, and ecologies, Aylin engages a multimodal framework of urban and sensory ethnography, expanded scenography, and feminist spatial practice.

Mateo Villegas, Antonia Roda, Daniel Avendaño, and Maria Jose Sanchez

The Amphibian City: An aquatory for more-than-human symbiosis

The more-than-human amphibian city will not be shaped by development as the single notion of the future. It will host many notions of natures and futures that coexist, allowing the preservation of a collective bio-social memory of the aquatory.

The more-than-human Latin American city is amphibious.

Most of our urban layout, despite being quite rigid, still has traces of what used to be our land in a past time, remembering the passage of rivers, wetlands, and settlements that highlight how it was to coexist with our aquatory. Before the European colonization, when it was still called Bacatá in the indigenous Muisca language, the land of Bogotá was covered by intricate networks of canals and ridges.

The Muisca engineering system embraced the seasonal flooding of Bogotá’s wetlands as an ally for collective well-being. Through canals and ridges, they applied the same principles of the aquaponic systems. During the wet season, they used the canals for fishing, while in the dry season, they cultivated food on soil enriched by the periodic floods. Muiscas planned their territory around water, and their agri-food and transport systems were intertwined.

The more-than-human amphibian city will not be shaped by development as the single notion of the future. It will host many notions of natures and futures that coexist, allowing the preservation of a collective bio-social memory of the aquatory.

As an amphibian, the more-than-human city will transition cyclically from the wet to the dry season, using not only the Muisca engineering system but also Western engineering knowledge. In the more-than-human city, water is treated as an asset rather than a hazard. It adapts traditional infrastructure such as highways, parks, or buildings with nature-based sponge (Rau S 2022) solutions that allow constant access to clean water for all humans and non-humans.

The Amphibian City will flourish thanks to the integration of ecosystem restoration, a renewed intricate network of canals, and smart city technologies. This engineered aquatory will restore adaptability to flooding through a system of sensors within sump wells and canal locks, creating a centralized feedback system that will serve multiple functions. On the one hand, it will prevent overflows by coordinating pumps, valves, and sensors to manage water distribution and balancing areas of excessive flooding with drier zones. On the other hand, it will remain continuously synchronized with the chemical composition, microorganisms, fish, and plant phenology, transforming floodwaters into a valuable resource for agricultural, aquacultural, and more-than-human community projects. The aquatory will work as a living adaptable and reproducible system.

The amphibian more-than-human city will be built considering humans as interdependent to the ecosystems they dwell in. Ecosystem services will be measured as services given by the city to all its inhabitants. The right to the city will be a right to the city for every living being. The Amphibian city will be a Symbiotic City (Stuiver 2023).

About the Writer:

Trophica Lab

Trophica Lab is a Colombian action think-tank of interdisciplinary young professionals dedicated to socio-ecological transitions. We integrate design, biology, anthropology, architecture, and engineering to create innovative, user-centered solutions. Through participatory and systemic design approaches, we develop projects that foster socio-environmental sustainability and drive urban, rural, and peri-urban regeneration. Mateo Villegas, Daniel Avendaño, Maria José Sanchez and Antonia Roda from the organization wrote this text together.