By Gravity Goldberg

Seventy percent of teens say anxiety is a major problem in their peer communities. Approximately two thirds of American children will experience at least one traumatic event by the time they are sixteen. At least sixty percent of students have been impacted by Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) which have been shown to create chronic stress.

Seventy percent of teens say anxiety is a major problem in their peer communities. Approximately two thirds of American children will experience at least one traumatic event by the time they are sixteen. At least sixty percent of students have been impacted by Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) which have been shown to create chronic stress.

This means that all of us teachers have students in the classroom that may be experiencing dysregulation. As teachers we can focus more on anxiety and students’ need for safety. When we bring this lens into classrooms, we notice nuances and can help students experience more regulation which is needed for any learning to happen.

Students who are anxious may look like this:

- Avoiding

- Daydreaming and staring off

- Fidgeting and leg bouncing

- Shrugging of shoulders

- Not knowing where or how to start

- Losing materials and being disorganized

- Asking for clarification

- Needing reassurance

- Head down on the desk

- Getting up and moving around

Many of us may have mistaken student behaviors as signs of misbehavior instead of dysregulation. If we see a student with their head down while we’re talking, we may even interpret it as a sign of disrespect.

A students’ body language is a window into their nervous system response and not necessarily a reflection of their feelings toward us or our subject. When we bring this perspective into the classroom, it helps us view behaviors as information we can use to better understand our students and how they are doing.

Dr. Stephen Porges developed polyvagal theory which explains how safety is experienced in bodies. Our bodies are built to perceive our environments and form conclusions about them. We do this through a process called neuroception. Neuroception is not just a visual and thinking based conscious process. It includes visceral feelings as well as environmental cues.

Based on our process of neuroception, our bodies make conclusions that may trigger us into fight, flight or freeze mode if a potential threat is discovered. The process of neuroception is an unconscious process that happens beneath the level of awareness. Our bodies do this to keep us safe without the need to direct our attention to the process.

When students are asked to pick up a text and begin reading, we teachers may not assess any threats but that does not mean students are having the same neuroception experience as us. In fact, what seems totally safe to us might feel quite threatening to them, such as reading a complex text, being asked to share out loud in front of peers, or being partnered with someone they don’t know.

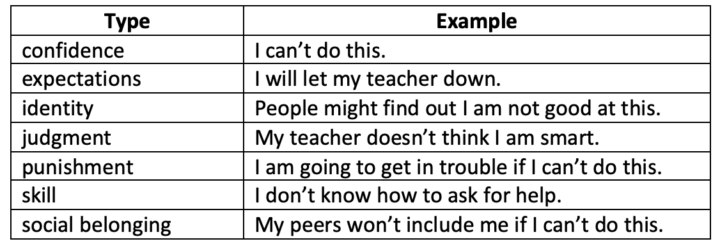

Types of Threats Students May Experience

To complicate matters, what looks like task avoidance and attention issues might be a nervous system response students have little control over. At the core of all of these fears is the fear of disconnection and of not belonging.

Teach kids about the autonomic nervous system

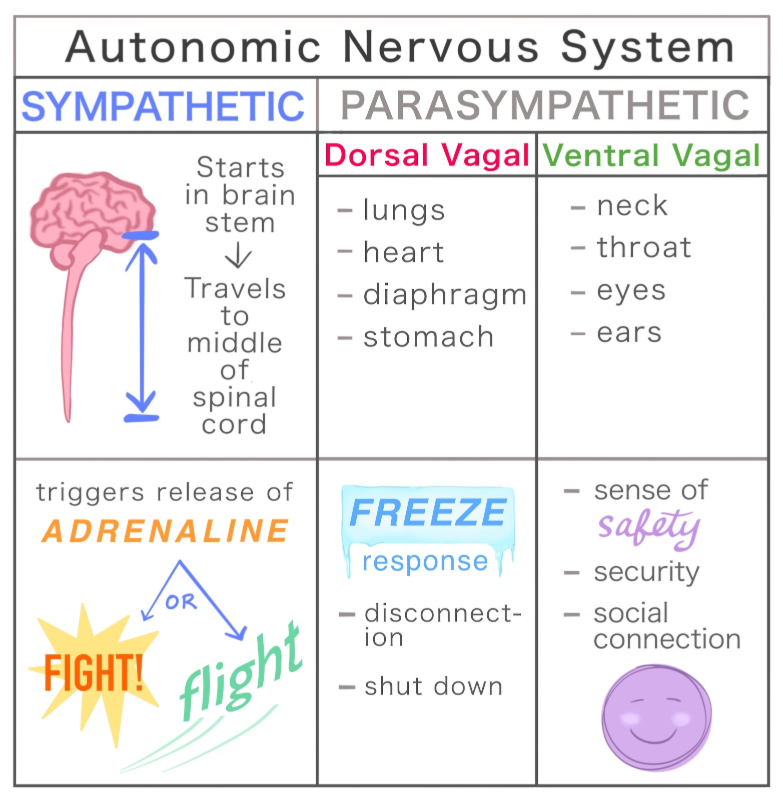

The autonomic nervous system is a two branch system in our bodies that helps us survive. The two branches include the sympathetic and parasympathetic responses that travel down three possible pathways. The sympathetic branch starts in the brain stem and travels to the middle part of the spinal cord. This pathway prepares our body for action by triggering the release of adrenaline that can send us into fight or flight.

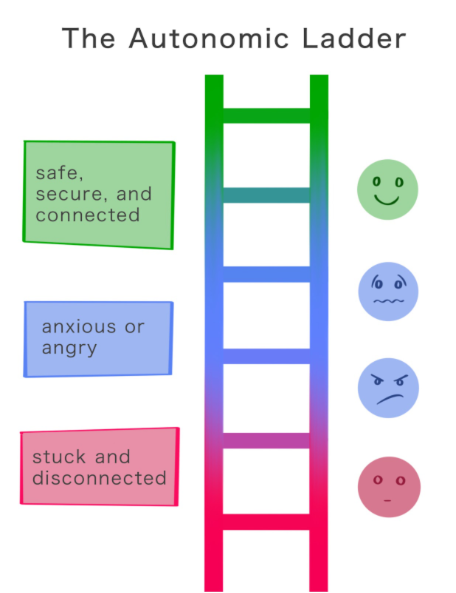

The parasympathetic branch, which is connected to the vagus nerve, has two possible pathways. The vagus nerve begins in the brain stem at the base of the skull and travels in two directions – downward through the lungs, heart, diaphragm and stomach, and upward to connect with nerves in the neck, throat, eyes, and ears. How a student perceives their environment triggers this nervous system response and impacts how and if they will be able to learn in the classroom. A ladder visual can be helpful to use when teaching students about how their autonomic nervous system works. Show them an image like the one that follows. Explain that it is totally normal, and part of being a human in community, to move along this ladder across the day.

A ladder visual can be helpful to use when teaching students about how their autonomic nervous system works. Show them an image like the one that follows. Explain that it is totally normal, and part of being a human in community, to move along this ladder across the day.

You can periodically pause and offer space for students to check in with themselves using the ladder. They might use words or emojis or both. Unless students volunteer to share where they are, there is no need to ask them to make this check-in public. If students (or any of us for that matter) spend too much time in the blue anxious or angry rung, we eventually get so overwhelmed that we move further down into the stuck and disconnected red rungs. When this happens, our brains are not open to teaching or able to access the information being shared.

If students (or any of us for that matter) spend too much time in the blue anxious or angry rung, we eventually get so overwhelmed that we move further down into the stuck and disconnected red rungs. When this happens, our brains are not open to teaching or able to access the information being shared.

That glazed over or numbed out feeling means we need to reset our nervous system before we can re-engage with the lesson. This feeling of being stuck may look like this:

- Ruminating on the past

- Worrying about the future

- Second-guessing

- Staring off into space

- Asking for clarification right after your teaching

- Shrugging shoulders as responses

- Wanting adult approval for every step of their work

- Waiting for an adult to get started

In order to help students experience more regulation and handle the threats they perceive, try the following practices.

Notice and Feel: Teach students how to recognize the signs in their own bodies that they are moving down the ladder. Offer space to pause and feel what the sensations are like so they can recognize them as they appear. It is likely different for each student.

Take a Brief Break: Let students know it is okay to take a break when they are recognizing the signs of fight, flight or freeze (the lower rungs on the ladder). If they can notice the cues before they get fully engulfed by the feelings, they may be able to pause on a rung and not travel any further. This brief break may be a time to get up and go for a walk or take a sip of water, a time to close their eyes and take some slow breaths, or a time to move to a “peace corner” set up in the room for times like this.

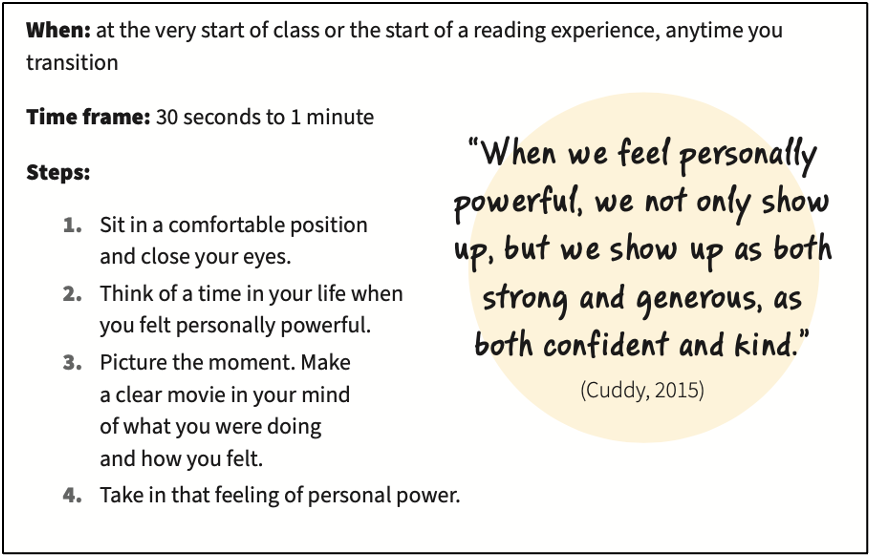

Ground: Proactively start lessons with a brief grounding practice to help prime students’ bodies to be ready to learn and experience more regulation. Try this sample grounding experience called Visualizing Personal Power.

Teachers need to check in, too

I’ve learned over the years that if I take a few moments across the day to check in with how my body is feeling and where I am on the autonomic ladder, I get more of a sense of my students as well. When I am feeling anxious, it is very likely that my students are too. I benefit from all of the same practices recommended for students.

While our bodies are connected to all of the learning happening in the classroom – through movement, social inferences, memory, executive functioning, gestures and so much more – the most important aspect to consider first is “Do my students feel safe right now?” If we ask this question first, before we even name the lesson objective or explain the success criteria, we are opening the path to an effective and human-centered learning environment where more students can be ready to learn.

Gravity Goldberg is an educational consultant and author of ten books on teaching including her latest release The Body-Brain Connection: Evidence-Based Ways To Reduce Anxiety, Boost Engagement, and Increase Comprehension In the Classroom (Corwin, 2025). During her 25 years of teaching she has served as a science teacher, reading specialist, third grade teacher, special educator, literacy coach, staff developer, assistant professor and yoga teacher.

Gravity Goldberg is an educational consultant and author of ten books on teaching including her latest release The Body-Brain Connection: Evidence-Based Ways To Reduce Anxiety, Boost Engagement, and Increase Comprehension In the Classroom (Corwin, 2025). During her 25 years of teaching she has served as a science teacher, reading specialist, third grade teacher, special educator, literacy coach, staff developer, assistant professor and yoga teacher.

As the founding director of Gravity Goldberg, LLC she leads a team that offers side-by-side coaching and workshops that focus on teachers as decision-makers and facilitators of student-led instruction.