As you navigate an election season that feels at times like an emotional rollercoaster, I hope you can find a sense of hope and solace in knowing that these plants and other species hold space for us regardless of who we vote for—we rely on them, and in many ways, they rely on us.

The notion of giving voice to more-than-human communities has long been of interest to artists, activists, and change-makers worldwide. Though still emerging, movements like the rights of nature have increasingly advocated for granting natural entities—rivers, forests, ecosystems—legal standing, akin to the rights given to people or corporations. Over the past several decades, several examples have emerged ranging from New Zealand’s recognition of the Whanganui River as a legal entity (2017), the Lake Erie Bill of Rights in Ohio (2019), Ecuador’s enshrining nature’s rights in its Constitution (2008), and Colombia’s Constitutional Court recognizing the Atrato River among others.

Yet, when it comes to giving nature political representation, there remain few examples where more-than-human communities are granted a direct vote or significant role in decision-making—despite their deep entanglement with human activities and policies. The limited examples we do have mostly come from contemporary art and the humanities, offering a thought-provoking and speculative look at what decision-making might look like if more-than-human stakeholders were given a legitimate voice and how they may actually influence policy. Consider, for example, The Party of Others by Terike Haapoja (2011), which uses immersive visual projections to propose a speculative interspecies party platform in Helsinki, Finland, advocating for the inclusion of non-human beings in local governance. Similarly, Future Assembly (2021) by Olafur Eliasson and Studio Other Spaces, presented at the Venice Biennale, envisions a future where non-human entities are granted agency in global decision-making, symbolized by a circular assembly space with objects representing non-human life forms. La voix des glaces (2019) by Robin Servant captures the haunting sounds of melting glaciers, using field recordings to translate their movement and eerie soundscapes into an auditory experience that highlights their fragility in the face of climate change.

Central to these works and the broader discourse of giving voice to nature, is the critical need to examine the ethics of translation. As Eben Kirskey (2014) describes in the Multispecies Salon, speaking on behalf and representing what nature “needs” or “says” can be easily reified as a form of ventriloquism that runs the risk of exploiting or anthropomorphizing more-than-human actors. To approach this thoughtfully, we need not only a radical commitment to deep listening but also a critical awareness of how we frame more-than-human organisms as “other”, and how political and economic systems shape our interactions with ecosystems and the species they support.

As we approach the 2024 U.S. presidential election in November, the idea of how nature is represented in our electoral process is fresh in my mind. This November is also a critical inflection point, particularly as a member of the Environmental Performance Agency, an artist collective founded in 2017 in response to the Trump administration’s efforts to dismantle the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (EPA was co-founded by members Andrea Haenggi, Catherine Grau, Ellie Irons, Christopher Kennedy, and spontaneous urban plants).

In 2017, outraged by the appointments of Scott Pruitt and Andrew Wheeler—both well-known fossil fuel lobbyists—we organized creative actions and artworks inspired by the resilience of urban plants, particularly species we often dismiss as weeds or invasive. As some of the most common vegetation encountered in urban areas, we felt a strong kinship with these resilient plants, not only for their ability to thrive in harsh environments but also for the essential ecological functions, habitats, and cultural services they provide to both human and more-than-human communities. Using this as both a lens and platform for artistic, social, and embodied practices, we advocate for the agency of all living performers co-creating our environment, specifically through the lens of spontaneous urban plants, native or migrant.

This year marks the 2nd presidential cycle where the resurgence of Trumpism looms. As the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency faces renewed threats, we look again to our resilient “weedy” plant allies for inspiration and guidance. In many ways, they offer a chance to reflect on the far-reaching consequences of political decisions, especially those made at the polls, which impact not just human communities, but all life on Earth. To foster this reflection, EPA agents Haenggi, Grau, and Irons developed a series of “scores”—invitations for deep listening and cultivating kinship with urban plants we affectionately describe as plant “specialists”. These plants have a remarkable ability to adapt and respond to human activities, making them valuable models for resilience in the Anthropocene. By engaging with their unique wisdom, the EPA hopes to offer a new perspective on how their adaptability can inspire decision-making in this era of ecological crisis.

Consider for example Prickly Lettuce (Lactuca serriola), the EPA’s Lead Program Analyst. Also known as the compass plant or opium lettuce, Lactuca serriola is an annual or biennial plant related to dandelions and known for sedative effects and used by ancient Egyptians as an aphrodisiac with pain-relieving effects ascribed to lactucarium, contained in milky white sap in stems and leaves. The leaves have a row of delicate spines along the mid-vein of the lower surface and are ingeniously held vertically in a north-south plane, perpendicular to direct sunlight. Prickly lettuce invites you to be scratchy―to reframe potential frictions as opportunities for new directions even if they push against the status quo.

|

DEMOCRACY DIVERSIFICATION Experiencing election apathy? Pause. Consult a plant. Consultant: Prickly Lettuce Visit prickly lettuce in the street. Greet the compass plant. Align your hand with one leaf, then with another. Wait for the sun to shift. Tolerate the friction. Stay in community. Ask yourself: What if plants led the way? |

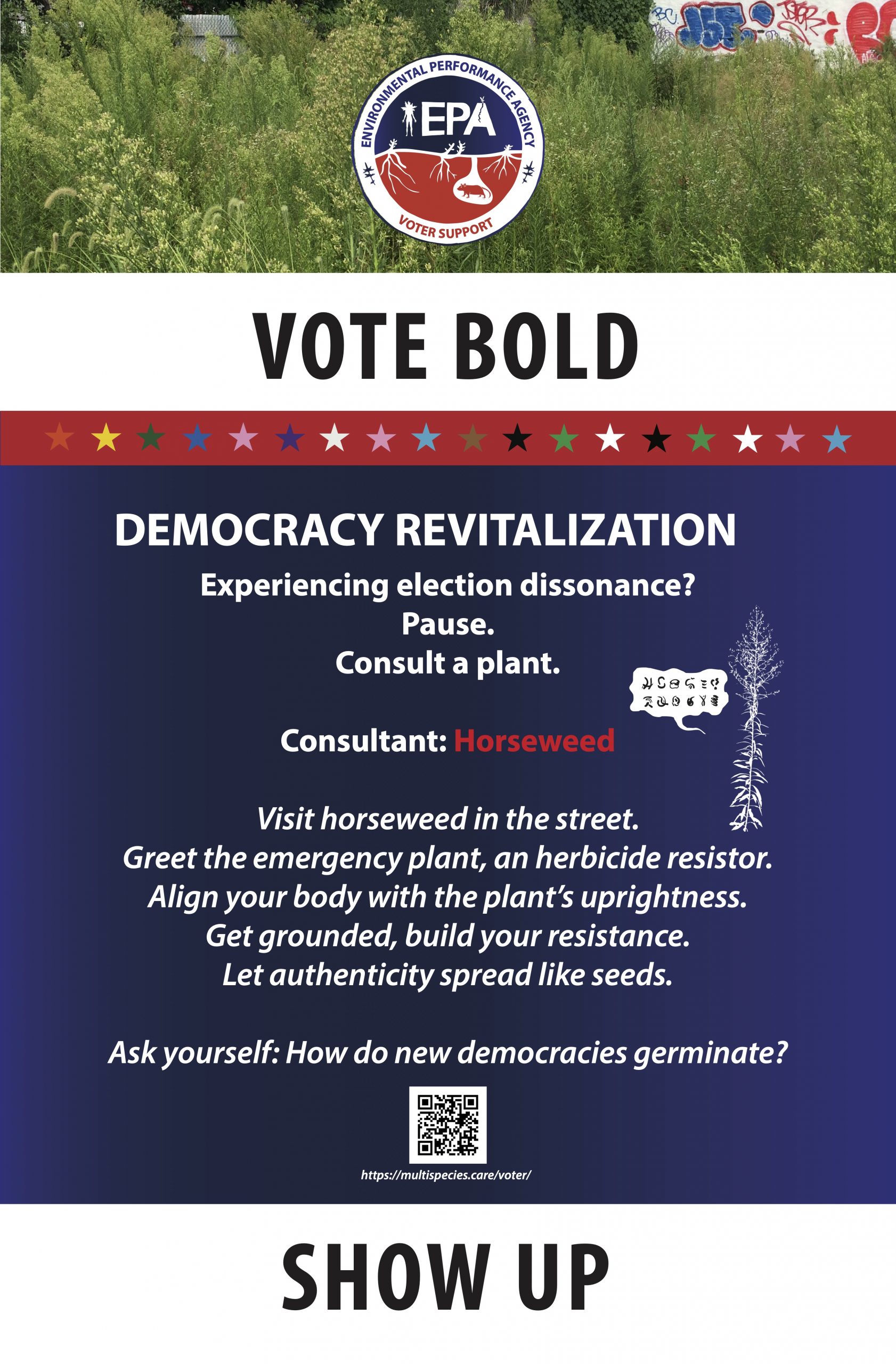

Next, the EPA invites you to commune with Horseweed (Erigeron canadensis), whom we’ve dubbed the EPA’s Herbicide Branch Chief. This resilient annual plant, native to much of North and Central America, grows as a tall, upright stalk encircled by leaves. Horseweed has adapted remarkably well to monoculture farming and holds the distinction of being the first species to develop resistance to glyphosate, a common herbicide. Historically, it has also been used medicinally to treat ailments ranging from diarrhea to headaches and earaches. Horseweed encourages you to stand tall, be bold, and reflect on the power of resistance. It prompts you to think about how you can best spread your ideas, seeds of change, within your community and beyond.

|

DEMOCRACY REVITALIZATION Experiencing election dissonance? Pause. Consult a plant. Consultant: Horseweed Visit horseweed in the street. Greet the emergency plant, an herbicide resistor. Align your body with the plant’s uprightness. Get grounded, build your resistance. Let authenticity spread like seeds. Ask yourself: How do new democracies germinate?  |

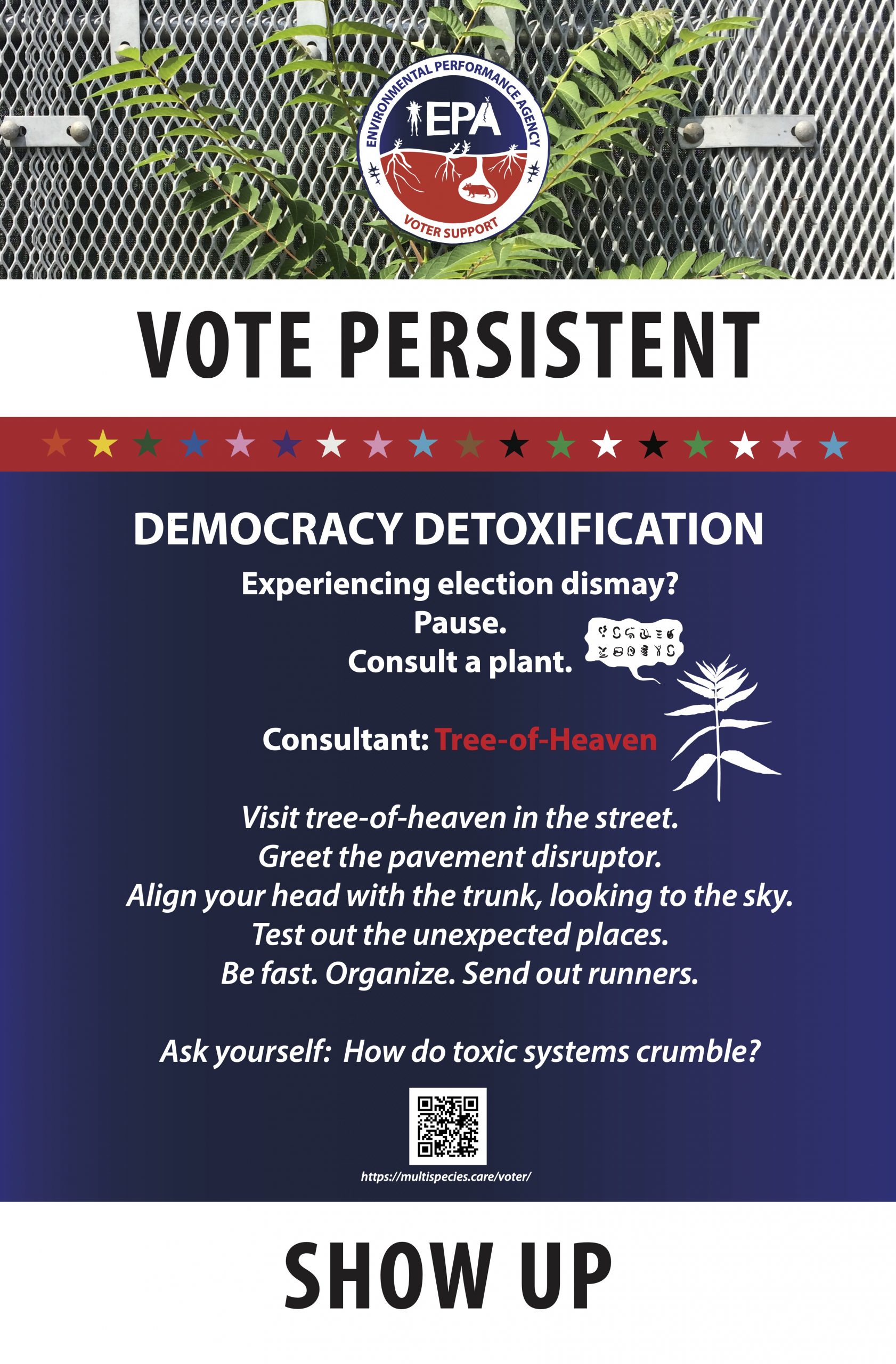

Finally, consider the Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima), the EPA Air Pollution Investigator. Originally brought from East Asia via Europe for both botanical and commercial purposes, it was once planted widely as a street tree due to its remarkable adaptability to polluted urban environments, but now widely considered an invasive pest. Despite its fast growth and short lifespan, the Tree of Heaven can reproduce vegetatively, extending its life and even fracturing concrete and other impermeable surfaces, aiding in stormwater drainage. It’s also culturally significant, lending its name to the classic novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. The Tree of Heaven invites us to be persistent, to disrupt toxic systems with actions that can break through and create space for renewal.

|

DEMOCRACY DETOXIFICATION Experiencing election dismay? Pause. Consult a plant. Consultant: Tree-of-Heaven Visit tree-of-heaven in the street. Greet the pavement disruptor. Align your head with the trunk, looking to the sky. Test out the unexpected places. Be fast. Organize. Send out runners. Ask yourself: How do toxic systems crumble?  |

While it is unlikely that you will see weedy plants like Horseweed or Prickly Lettuce on your local ballot anytime soon, there is immense value in imagining how other species could be included in our political processes and governance. Our lives are deeply entangled with those of other species, forming a mutual interdependence that many believe is crucial for our survival. As you navigate an election season that feels at times like an emotional rollercoaster, I hope you can find a sense of hope and solace in knowing that these plants and other species hold space for us regardless of who we vote for—we rely on them, and in many ways, they rely on us. Let them serve as guides and reminders of our shared kinship, and perhaps an invitation to consider a new multispecies approach to governance that can foster a greater sense of connection in a time of immense uncertainty and change.

Visit us online at https://www.environmentalperformanceagency.com/ and to share or download a copy of the Multispecies Vote posters visit: https://multispecies.care/voter/

Christopher Kennedy

San Francisco

About the Writer:

Christopher Kennedy

Christopher Kennedy is the assistant director at the Urban Systems Lab (The New School) and lecturer in the Parsons School of Design. Kennedy’s research focuses on understanding the socio-ecological benefits of spontaneous urban plant communities in NYC, and the role of civic engagement in developing new approaches to environmental stewardship and nature-based resilience.