By Laurie Miller Hornik

Before AI it was fairly easy to teach students what academic honesty was and how and why they should do their own work. That doesn’t mean they were never dishonest, but the logic behind academic honesty was clear.

As AI becomes more prevalent, it can be tricky even outside of a school setting to say exactly what “doing your own work” means.

Adults are using AI to help with more tasks each day. Some experts argue that, since students will become adults in a world where AI might be a thinking partner for most human tasks, we should devote time in school to teaching students to use AI.

I am not convinced. For now, in middle school classrooms, “doing your own work” still seems pretty straightforward. The same way we ask young cildren to learn to do arithmetic themselves before turning to calculators, middle school students need to develop independent reading, writing, and thinking skills before turning to AI technology.

For now, in middle school classrooms, “doing your own work” still seems pretty straightforward. The same way we ask young cildren to learn to do arithmetic themselves before turning to calculators, middle school students need to develop independent reading, writing, and thinking skills before turning to AI technology.

Part of teaching students to think involves teaching students to think about this issue. So this year, instead of simply telling my students all the things they were not allowed to do (no ChatGPT, no Gemini, etc.), I tried a different approach. I engaged them in thinking about the “why.”

Would you let a robot do it for you?

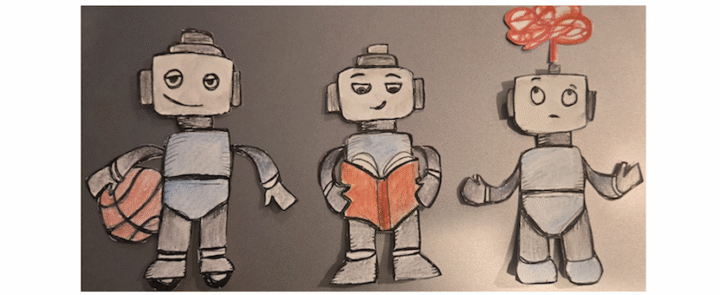

I began like this: “Imagine you are offered a robot to play basketball for you. You would ‘get credit’ for playing, but wouldn’t have to actually play. Would you accept the offer?”

The majority of students were aghast at the question, immediately proclaiming they would never allow a robot to play sports for them. A few students quietly admitted that they didn’t care about playing basketball, and they might consider it, although some of these students said they did care about getting exercise, so they might still not use the robot.

Next, I asked them about basketball practice. If they wouldn’t let the robot play in the basketball game for them, what about the boring parts of basketball practice? Again, most students readily exclaimed that the drills were important: You couldn’t learn to play well without them. Some students seemed to bring an ethical sense to it about what is fair. Others were more practical. Both approaches led students overall to say “no.”

I told students then about my own feelings about driving. I grew up in Manhattan, and my parents never had a car. They didn’t drive, and neither did I. It wasn’t something I ever valued. Eventually I did have to learn to drive to transport my children from activity to activity, but I never grew to care about driving.

“I would absolutely get a self-driving car,” I told my students. “I have no issue with a robot doing the driving for me.”

My students were shocked. Many of them very much look forward to learning to drive in a few years. But my point is that it isn’t necessarily wrong to let a robot do certain things for you. What matters is that you take the time to consider what you care about doing yourself and what you feel comfortable letting a robot (our shorthand for AI) do for you. And this can differ from one person to the next.

I invited my students to consider the following questions:

- What would you NEVER want a robot to do for you?

- What would you ALWAYS want a robot to do for you?

- What would you SOMETIMES want a robot to do for you?

Students shared in partners and then with the larger group. I helped them focus on our differences – how reasonable people can disagree about whether or not they would use a robot to vacuum for them or drive them around or feed their cats.

Then I asked them to think about thinking: “Would you want a robot to do your thinking for you? What would that mean? What would that look like?”

Everyone agreed they did not want to have a robot do their thinking for them. Thinking, they understood, doesn’t just mean looking up information. It is what you do with the information – the process of examining it and making sense of it, of making connections, decisions, and judgment calls.

I hearkened back to our basketball analogy: What about the “practices” for thinking? What about the homework assignment that seems boring or repetitive? Here students admitted that if they didn’t see the purpose in the assignment, if they didn’t think it would help them, they could imagine wanting to let a robot do it for them. Some still said they wouldn’t because it seemed ethically wrong.

But this was a good reminder to me, as their teacher. Students care about doing activities they find meaningful. More than ever, it is important that teachers help students find meaning in their schoolwork.

As AI presents more and more as magic, or as part of the world around us, it’s not enough to simply tell students not to use it. If we value teaching students how to think, the question of when to use AI is a great place to put these thinking skills to work.

Laurie Miller Hornik is a K-8 educator with over 30 years of experience. Currently, she teaches seventh grade English at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in NYC. Laurie is the author of two middle-grade humorous novels, The Secrets of Ms. Snickle’s Class (Clarion, 2001) and Zoo School (Clarion, 2004). She publishes humor at Slackjaw, Belladonna Comedy, Frazzled, and on her own Substack, Sometimes Silly, Sometimes Ridiculous. She also creates mixed media collages, which she shows and sells locally and on Etsy.