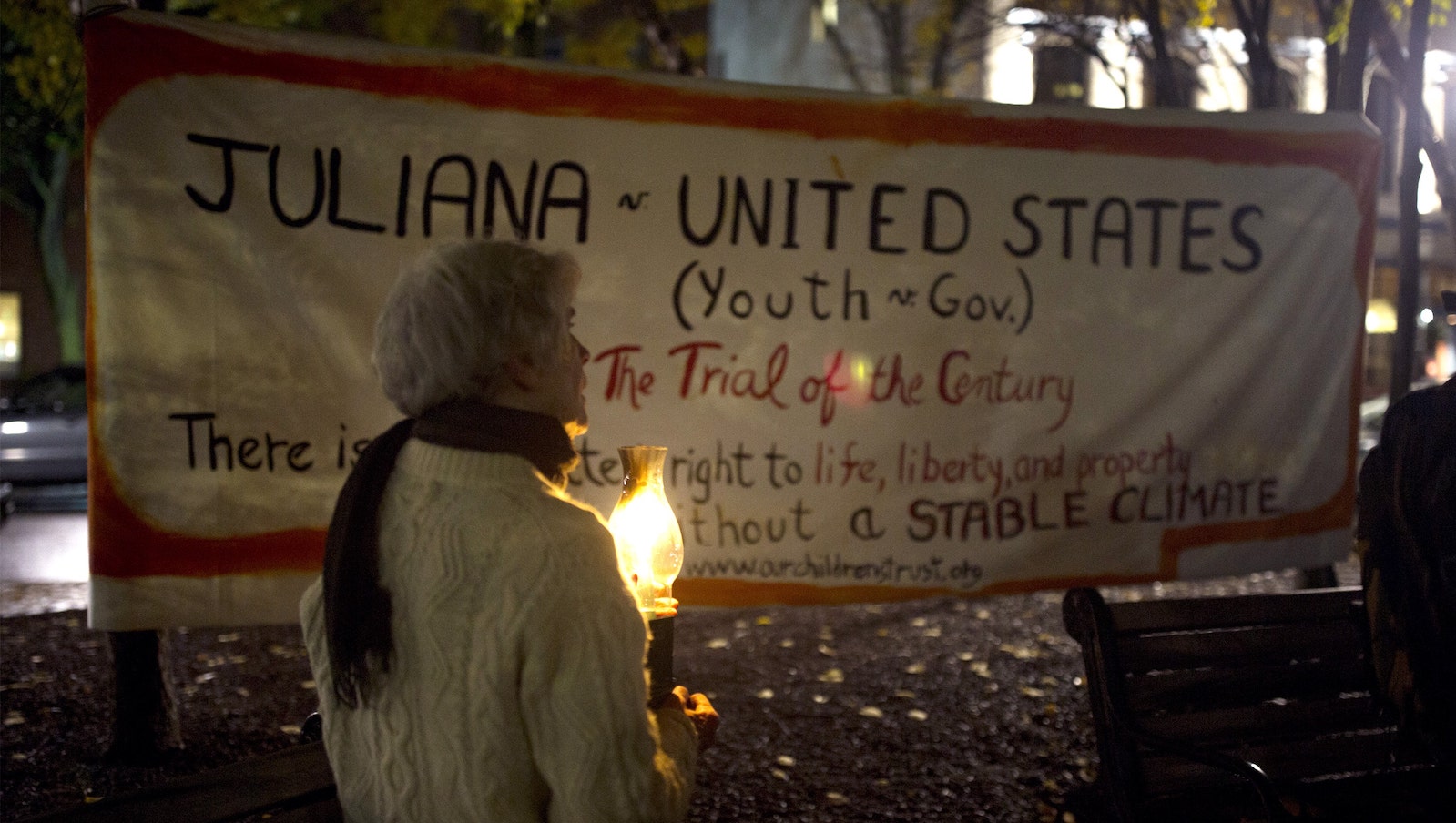

Miko Vergun, a plaintiff in the landmark 2015 federal youth climate lawsuit Juliana v. United States, which questioned the constitutionality of 50 years of government support for fossil fuels, wasn’t surprised on the first day of President Donald Trump’s second term when he issued three executive orders meant to clear the way for the drilling of more oil and gas and the mining of more coal in the name of energy security. She was nevertheless “disheartened” that her government planned to redouble its support of fossil fuels even in light of the harm climate change was causing.

Then three months later, she learned that the U.S. Supreme Court would not reconsider its 2020 dismissal of Juliana — after a decade, her case was over. “After Juliana, truthfully, I had given up hope,” she told Grist.

The Juliana case was the first in a series of lawsuits brought by the nonprofit law firm Our Children’s Trust on behalf of youth plaintiffs. In August 2023, they won their case against Montana, which argued for a “fundamental constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment,” and now the state must consider greenhouse gas emissions and their impacts in its permitting process. In 2024, the state of Hawaiʻi settled a case brought by Our Children’s Trust, agreeing to decarbonize its transportation system and reach zero emissions by 2045.

In spring of this year, Our Children’s Trust invited Vergun to join another lawsuit — challenging the constitutionality of Trump’s three executive orders, “Unleashing American Energy,” “Declaring a National Energy Emergency” and “Reinvigorating America’s Beautiful Clean Coal Industry.”

Vergun had her doubts. “It’s really easy to take a nihilistic view, especially in these uncertain times,” she told Grist. “But I woke up one day, and I was like, ‘Yeah, I want to join.’”

In September, after the initial court proceedings, Vergun, her lawyers, and 21 other plaintiffs, ages 7 to 25, met in a Missoula, Montana, courthouse for the evidentiary hearing in a new case, Lighthiser v. Trump. The hearing was a sort of mini-trial in which both sides were given a chance to present their arguments and to question witnesses. The testimony was both emblematic of Our Children’s Trust’s approach and indicative of their evolving strategy.

Photo by Alex Wroblewski / AFP via Getty Images

On the first day of the hearing, gray fog cloaked downtown Missoula, but the young plaintiffs bubbled with excitement as they strode toward the red-brick courthouse through a pathway festooned with marigolds. About 100 supporters carrying signs cheered as they entered the courthouse and filed up to the second floor. Once everyone settled into the long wooden rows facing the judge’s bench, Julia Olson, the lead attorney for the plaintiffs, rose for her opening statement. “This case asks a fundamental question,” she said. “Does the United States Constitution guard against abuses of power by executive order that deprive children and youth of their fundamental rights to life and to their liberties?”

It’s a question that, according to Mary Wood, professor of law at the University of Oregon, distinguishes the legal strategy in Lighthiser from Juliana. The earlier case asked the court to order the government to prepare and implement a plan to fix climate change. This time, plaintiffs are seeking a narrower remedy — an injunction to stop implementation of the three specific executive orders. “It’s a discrete request in the here and now designed to prevent further, ongoing harm,” Wood said.

But it wasn’t a difference the government lawyers conceded. “Here we are back again, attempting to deal with fundamentally the same legal claim all over again,” Department of Justice attorney Michael Sawyer said in his opening argument. The plaintiffs, he said, want the courts to “step in and exercise general supervision over the nation’s energy policy.”

Since the defendants declined to call any witnesses, Our Children’s Trust had two days to make their case. They began with young plaintiffs. First Olson called to the stand Joseph Lee of Fullerton, California, a wiry 19-year-old with long bangs and glasses wearing a dark suit and sneakers. He raised his right hand and became the first youth in history to testify in a federal youth climate case against the U.S. — something that Our Children’s Trust had been working toward for more than a decade. Sitting in the witness stand, Lee recounted growing up near an oil refinery and developing asthma; how heat, humidity, and wildfire smoke made it feel like his lungs were filled with water; how he has been hospitalized multiple times, once even surgically intubated during a heat wave. “I’m not sure if I can go on,” he said.

Olson asked him: “Will stopping the EOs end climate change?”

“No,” he replied. “But it will stop it from getting worse.”

In cross-examination, DOJ attorney Erik Van de Stouwe noted the lack of air conditioning in Lee’s dorm at UC San Diego and how that must aggravate his asthma. “But you didn’t take legal action against the State of California, right?

“To categorize the years of struggles I’ve had into a mere issue of air conditioning is something that’s hurtful,” Lee replied.

The second witness, Jorja M., 17, told the court about grabbing her stuffed animals when a wildfire threatened her home in Livingston, Montana. She testified about a 2022 flood that crept up to the door of her family’s vet clinic, “even though we are not on a floodplain.” She described black coal dust from trains coating her home and irritating her nose, throat, and lungs. The coal came from Colstrip, a plant that was scheduled to close and will now remain open following the Trump executive orders.

As the government’s attorney Miranda Jensen approached the witness stand, Jorja shifted nervously in her seat. “You testified that you have three horses, right?” Jensen asked.

“Yes,” Jorja answered.

“And you’re aware that raising horses contributes to global warming?”

“I am aware of that, yes.”

“Are you concerned by the emissions that your horses contribute to the problem?”

Gasps of exasperation arose from the audience.

“I think that having three horses has minimal emissions,” Jorja said.

After answering more questions, Jorja returned to her seat in the gallery and caught eyes with Avery McRae, the next plaintiff to testify. They smiled knowingly at each other.

After she was sworn in as the next witness, Olson asked McRae, 20, to describe struggling to care for her horse and other farm animals during wildfires and heat waves that have been plaguing Oregon. McRae remembered “coughing” and “feeling awful.” As she continued on with her testimony, McRae described moving to Florida for college, only to walk right into a different sort of climate disaster: In her first three years, she had to evacuate for three massive hurricanes. “The whole campus was inundated with sea water,” she said, her voice calm but tinged with anger. She had to pay for an Airbnb, huddle in a closet during a tornado warning, and fly home to attend class on Zoom for five weeks.

In the cross-examination, the government lawyer clarified which climate disasters happened before Trump signed the executive orders and which happened after.

Olson had a chance to redirect.

“Are you bringing this case to remedy past injuries?” she asked.

Avery answered, “No.”

“Are you asking the court to provide the remedy of stopping the EOs?”

“Yes.”

With those testimonies, Our Children’s Trust had begun to lay out its basic argument — that its clients are suffering from climate change and Trump’s executive orders will make it worse, a violation of their constitutional rights to life and liberty. Their legal strategy for the rest of the hearing depended heavily on what Wood, the professor at the University of Oregon, called “an all-star cast” of fact witnesses.

The afternoon testimony opened with Steve Running, a white-haired man in a gray suit who joked he might be the oldest person in the courtroom. Running, who shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for his work with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, testified that science has established that the burning of fossil fuels releases greenhouse gases, which warm the planet and harm the plaintiffs. “Every additional tonne of CO2 matters to the whole world and definitely matters to these plaintiffs,” he said. When asked if the executive orders would make the youth’s injuries worse, Running answered, “Unquestionably.”

Excitement was palpable in the courtroom as Olson called John Podesta to the stand. Podesta was an adviser for former president Joe Biden on clean energy and climate policy when Juliana was in pretrial motions. He and the Biden administration took the position that the argument in Juliana was too broad to implement, so his appearance here was striking.

Olson asked Podesta to explain how executive orders were created and administered. Then she said: “Mr. Podesta, is it fair to say that if an executive order is enjoined, that [government officials] could ensure implementation of that court-ordered injunction?” she asked.

“It would be incumbent on every agent of the federal government who has taken an oath of office to abide by that order, up to and including the president,” he answered. In cross-examination, Sawyer, of the DOJ, worked to get to the heart of the government’s defense — that the plaintiffs are asking the court to weigh into a policy debate. “President Biden also issued day one executive orders, right?” he asked.

Podesta nodded. “Yes.”

Sawyer led Podesta through a series of questions about Biden’s executive order, which compelled the executive branch agencies to take actions geared toward addressing climate change — and which one of Trump’s orders revoked. Sawyer’s main point was to make the case that signing executive orders that revoke a prior administration’s policies and establish new ones is just something that presidents do.

When court recessed for the day, the young plaintiffs chatted warmly with the experts as they exited, thanking them for their support. All the experts had testified for free. On the second day of the hearing, dawn broke brightly, the sun rising over the golden hills surrounding Missoula. In the court room, the young plaintiffs stood in the rows of wooden benches, chatting and laughing quietly as the lawyers hustled to take their seats. The witnesses included an energy economist, a pediatrician, and one more young person.

In her closing arguments, Olson attempted again to draw distinctions between Lighthiser and Juliana, and underscore the injuries that her clients are experiencing, which, she argues, are being worsened by the government’s actions. The judge jumped in. “What is it that you want me to do?”

“The remedy is a simple one,” Olson answered. “It’s enjoining the government from implementing the three executive orders and the specific provisions within them that we have alleged are infringing the plaintiffs’ rights.” The judge expressed concern that a ruling in their favor would lead to an ongoing judicial monitoring of the administration’s actions.

“Your Honor, it’s not about policy choices,” Olson countered. “The Supreme Court has said, in case after case after case, that the fundamental rights to life and liberty don’t get put to a vote. If policymakers could decide to threaten children’s lives, then the Bill of Rights would mean nothing.”

In the government’s closing arguments, Sawyer said the judge was correct to be concerned about wading into a policy issue that should be addressed by Congress and the executive branch. Linking government actions to the rights to life and liberty is, he warned, “a one-way ratchet for safety-ism.”

Judge Christensen has not indicated when he will rule on the plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction, which would put the executive orders on hold until there is a trial to decide the case. The defendants have also filed a motion to dismiss that is before the court.

According to Mat Dos Santos, co-director of Our Children’s Trust, all the youth climate cases, including Lighthiser, aim to place bumpers on government action — like in a bowling alley — so governments are nudged into taking greenhouse gases and kid’s lives and health into account whenever they set policies.

The key question facing the judge, according to Michael Gerrard, the director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University, is whether there is a constitutional basis for the court to act. Striking down executive orders “can be done in a proper case if there is a legal basis for it,” Gerrard said.

Miko Vergun, for one, is still hopeful. “I’m just waiting for good news, to be honest,” she said.