By Laurie Miller Hornik

At the progressive college preparatory school where I teach, the seventh grade English curriculum uses the standard model of (1) read and discuss a book together as a whole class and then (2) write an essay about the book or sometimes a piece inspired by the book.

Early in the year, we read The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros and the students write their own vignette collections.

Later, we read Lord of the Flies by William Golding, and the students write essays about responsibility (see my article). Near the end of the year, we read Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s beautiful book of personal essays, World of Wonders, and students write their own essays about “wonders” of the natural world.

We read six texts together across the year. Along the way, students are also expected to engage in nightly free reading, but in the past many have been reluctant to do so.

I get it. Students are busy. They have six classes, maybe eight classes. They have after school activities. They have social lives – in person and online. Increasingly, free reading is what drops away. And yet, studies (1996, 2020) show that the more students read, the more they develop as readers, writers, and thinkers. What to do?

Last year, I decided to look for new ways to center free reading without giving up the whole-class-book model. I began by reviewing the lessons I use while we are reading whole-class texts. For each lesson, I considered whether it was more important than free reading or not. Which lessons contributed significantly to student learning? Which were not necessarily more valuable than time spent reading? This helped me pare down the teacher-centered lessons, and free up enough time for “Free Reading Friday,” discussed below.

When Can Students Free Read?

The English classes at my school usually begin each class with ten minutes of free reading. We realized years ago that this was the perfect “Do Now” for English class. As students settle in, they take out their books and begin to read, creating a quiet, productive atmosphere and sense of community. This routine gives students daily accountability for their reading (What are they reading? Did they bring their book? Are they actually reading?). And seeing them reading each day helps me get to know the students as readers.

The rest of free reading is scheduled for outside of class time. Our school expects students to read for 20-30 minutes (almost) every day outside of class. Last year, I found it worked better to help students create week-long free reading goals rather than nightly ones.

Most students were able to commit to reading 100-150 pages per week. This worked out to be about the same amount of time as they were spending before, but the weekly goal gave them more agency in deciding when to read, and many students reported that this helped them develop a better reading routine.

Free Reading Friday: What It Is and What It Isn’t

Students don’t spend “Free Reading Friday” reading. Instead, our Friday class is focused on talking and writing about free reading. Free Reading Friday gives students a stronger sense of purpose and accountability for their free reading during the week, which in turn helps them increase the reading they do outside of class. It also creates a shape for the week.

This was an unexpected benefit: Students enter class on Friday delighted to spend it talking and writing about their free reading. I could have called it “Weekly On-Demand Writing” and that would have been accurate, but the students and I think about this writing more as an exploration and a chance for them to articulate their thinking about their free reading. It feels – to the students and to me – like a special way to end our week together.

Free Reading Friday begins with students in pairs, usually with an assigned partner with whom they are already working. For ten minutes students talk with their partners about their books, responding to four prompts: (1) What are you finding interesting or enjoyable about your book? (2) What questions do you have or what are you curious about in your book? (3) How far will you plan to read by next Friday? and (4) a unique prompt just for that day, which serves as a rehearsal for the writing they will do individually for the rest of the period.

Students also let me know how far they intend to read by the following Friday. They know they can always read more than that: the target number of pages is meant to inspire, not limit.

Writing about Free Reading

After the partner talks, each student grabs a Chromebook and writes off the assigned prompt, which they already rehearsed. I call this writing their “Free Reading Journal” (FRJ), and in our 45-50 minute period, students usually end up with about 30 minutes to complete it. A few students get so engrossed that they choose to continue working on it over the weekend, but the intention is for it to be classwork.

I let them know that their goal is to show their best thinking about their free reading book, not just what happened. Their weekly FRJ assignment often gives them the chance to be creative or to apply skills from class in a new context.

Here are a few examples of FRJ Prompts I created to go with our work in class.

►FRJ: Argument/Counterargument

After we finish reading Lord of the Flies and students write argument/counterargument essays, an FRJ asks students to think of a claim about their Free Reading Book. They then write an argument supporting the claim and a counterargument pushing back against the claim.

►FRJ: Paint Chip Poetry Cards

This game comes with 400 “paint chip” cards – each a different color with a poetic “paint chip” name. I give each pair of students a handful of cards and ask each of them to choose THREE cards that go with their book in interesting ways, either because of the color or the name of the color. They explain their colors/book to their partner and then write about them in the FRJ.

►FRJ: Choose Five

►FRJ: Choose Five

During partner talks, students choose five vocabulary words from class that will best help them discuss their specific book. They explain to their partner why they chose the words they chose. Then, for the FRJ, they write a paragraph about their book using the five words. The most interesting part of this FRJ is the process by which students choose the words they will use. They end up discussing many of the other vocabulary words and ruling them out as they decide.

Responding To Free Reading Journals

I don’t consider these weekly writings to be major assignments; instead, they remind me of the Reading Journals from when I taught third grade. My third graders would write me a letter each week, and I would write back.

This was an onerous routine, and what I’ve learned over the years is that onerous routines are hard to keep up and are seldom worth it. So I read my students’ weekly FRJs quickly and write each student a short comment, responding to the ideas in it rather than evaluating how good a job they did. This keeps the focus on the thinking and on the reading itself.

How It’s Going So Far

Free Reading Friday has transformed my class into a reading community, without having to give up our whole-class-text experiences. Students arrive on Fridays excitedly saying, “Oh! It’s Free Reading Friday!” They tell me they like the routine of knowing what Friday’s class will be. They also like that they get “credit” for their free reading.

They are reading more than they used to, and I can tell from their writing that they are thinking deeply about their books and understanding them. They are developing meaningful reading lives.

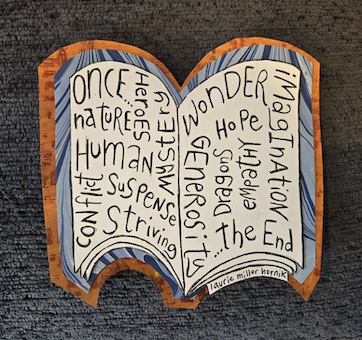

Laurie Miller Hornik is a K-8 educator with over 30 years of experience. Currently, she teaches seventh grade English at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in NYC. Laurie is the author of two middle-grade humorous novels, The Secrets of Ms. Snickle’s Class (Clarion, 2001) and Zoo School (Clarion, 2004). She writes a weekly Substack of humorous essays called Sometimes Silly, Sometimes Ridiculous and creates mixed media collages, which she shows and sells locally and on Etsy.