A MiddleWeb Blog

It was my senior year of college, and I had to take my last science requirement to graduate. I had to write the background section of a report in which I described the different rocks in the local limestone creek. This sentence, The shale is sandwiched between the sandstone and composite rocks layers, had multiple angry swirling red circles, accompanied with a “Please see me!”

It was my senior year of college, and I had to take my last science requirement to graduate. I had to write the background section of a report in which I described the different rocks in the local limestone creek. This sentence, The shale is sandwiched between the sandstone and composite rocks layers, had multiple angry swirling red circles, accompanied with a “Please see me!”

When I met with my instructor she said, “This type of writing is not used in science.” She explained that scientists do not use figurative language when writing. They use expository writing that analyzes facts and statistics objectively.

I was shocked. I thought that the writing used in a literature class was the kind of writing used in all subjects. After all, wasn’t that the goal of English classes – to teach me to write in English?

Filling the academic writing gap for MLs

From that experience I learned that each subject has its own rules and format for writing. This was never taught in any of my classes. I was assigned writing tasks but never explicitly taught how to write in the appropriate way. After years of figuring out how to teach writing to MLs – especially those who are no longer beginners – I’ve refined my process for explicit academic writing instruction.

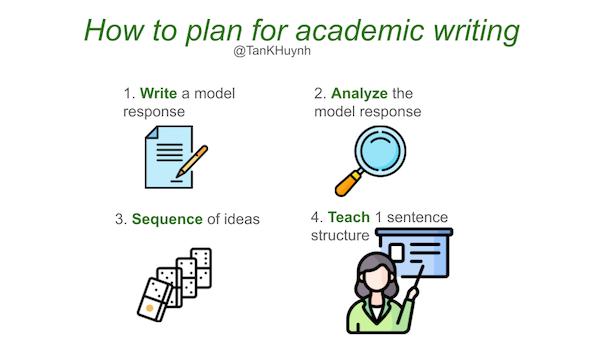

Step 1: Write a model response

All educators know what they want students to write about when assigning a writing task. Topics are found in the instructions they often provide, but few students can identify the linguistic requirements to fulfill that task from the instructions alone. When teachers are writing a model response appropriate for their grade level, write the highest quality example that your students can produce. Include the required content and the formatting (e.g. citations).

Generally, I do not give my students my model response. I want them to generate their own ideas. The model response is just to help me identify the linguistic requirements I expect them to meet. If, however, I have a model response for another topic on hand, and think it might help them understand my requirements, sharing that model response is appropriate. I might also share a model response with some students but not others, based on individual needs.

Step 2: Analyze the model response

When we have our model response written, we can use it to identify the linguistic requirements of the task. Analyzing our model response reveals the:

- tense

- transitions

- vocabulary

- sentence structures

- sequencing of the ideas

Identifying all of these things helps us map out the linguistic requirements of the task. Instead of “hoping” students will produce this level of writing, now we have a clearer vision of the learning journey students have to travel to communicate at this level and how we need to support them.

Step 3: Sequence the ideas

The sequencing of ideas can be elusive to multilinguals. Many simply do not know where to start or how to structure a paragraph, let alone an essay. We can scaffold the linguistic requirements by writing prompts or guiding questions for MLs.

List these prompts in the particular order that the ideas should appear in their writing. For example, here is the sequencing for a short-answer response about what a major cause of the French Revolution might be:

►Identify one thing that can cause a revolution.

►Explain how this cause was a factor in starting the FR.

►Provide a specific example of this cause before the FR began.

►Explain how this example shows that this cause was a major one in producing the FR.

Providing sequenced prompts like this helps students communicate more logically, resulting in clearer expression of ideas. With this type of scaffold, MLs not only know the content they have to write but also have a sequence to communicate these ideas. This step keeps the academic challenge while scaffolding the linguistic demands.

Step 4: Teach a helpful sentence structure

Complex sentence structures are one feature of academic writing. However, MLs often use social language when writing as they have not been taught to make the transition to an academic register. One way to explain this shift is by teaching the sentence structure that meets the central task of the writing prompt.

For example, when writing about the major cause of the French Revolution, I identified that a sentence starting with a “When” subordinating conjunction works best to communicate a cause-effect relationship…when/then. Before having MLs write their paragraph, I explicitly teach them how to write sentences with “When” about a situation not connected to the FR (e.g. sports, holiday, a pet, a family member). Then MLs practice writing a “When” sentence for the FR, which they can then use in their short answer response later.

Conclusion

Writing for academic purposes is different from writing for social purposes such as leaving a comment on a video or writing a caption for a photo posted on a social media platform.

Multilinguals can be taught to use academic language in their writing when we explicitly teach it. The process takes more time than simply assigning a task and assuming students have the skills to produce the desired writing.

With this process MLs will become more successful in our classes as they become more confident in their ability to use academic language in their writing. While teaching content is discipline-specific, when we teach MLs to acquire academic language, they will be successful across the disciplines.

If you are an ELD teacher or a secondary content teacher and found this article helpful, you might be interested in reading Long-Term Success for Experienced Multilinguals, a book I co-authored with Beth Skelton, which is devoted to supporting content teachers as they instruct MLs who have already acquired social language.

If you are an ELD teacher or a secondary content teacher and found this article helpful, you might be interested in reading Long-Term Success for Experienced Multilinguals, a book I co-authored with Beth Skelton, which is devoted to supporting content teachers as they instruct MLs who have already acquired social language.