By Frank W. Baker

In a recent MiddleWeb article, Teaching Kids About AI and Other Media Risks (October 2025), I wrote of the urgent need for us to redouble our efforts in teaching critical thinking, healthy skepticism and media literacy. But what does it mean to teach 21st Century media literacy? And how might more teachers get involved?

In a recent MiddleWeb article, Teaching Kids About AI and Other Media Risks (October 2025), I wrote of the urgent need for us to redouble our efforts in teaching critical thinking, healthy skepticism and media literacy. But what does it mean to teach 21st Century media literacy? And how might more teachers get involved?

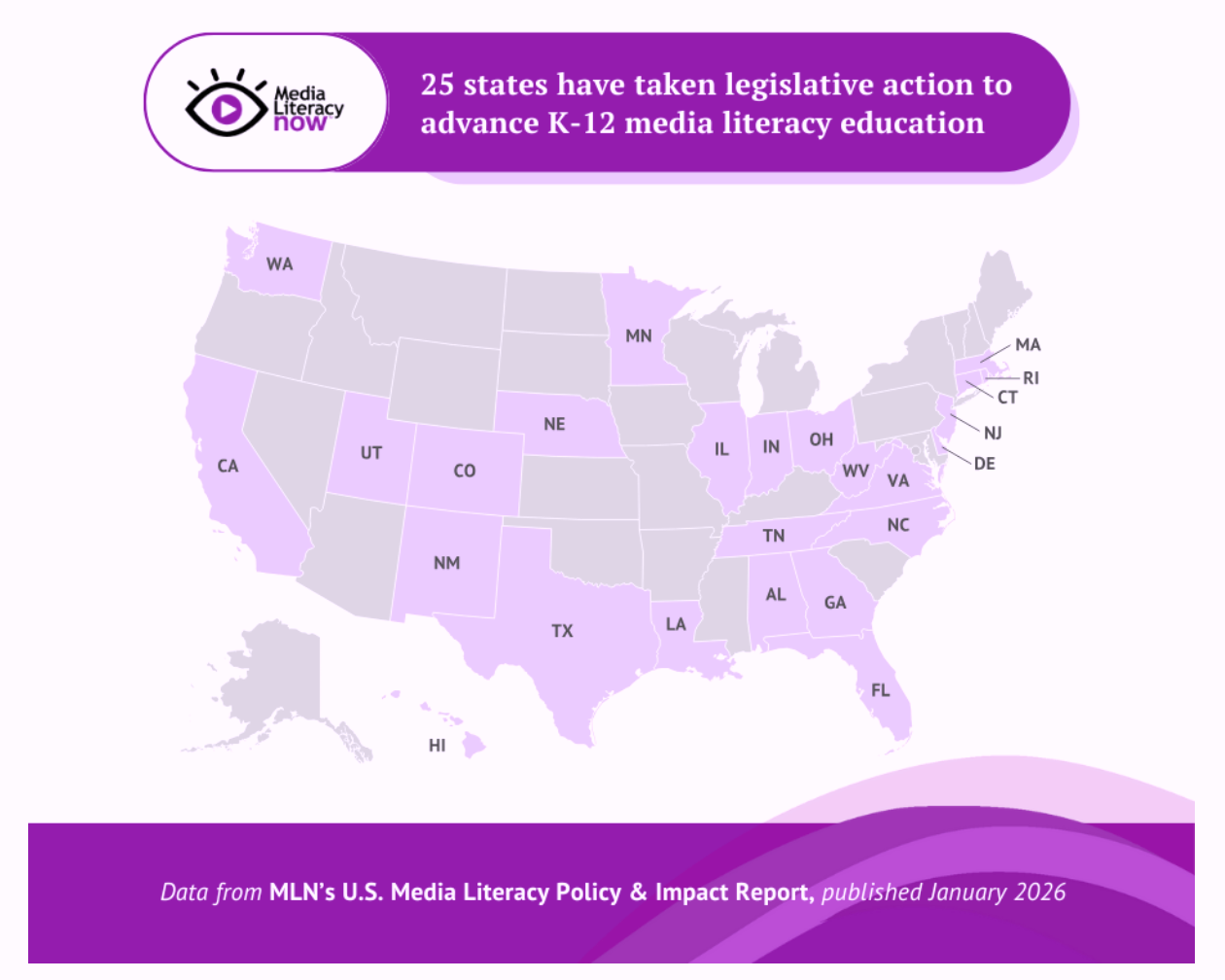

Recent research in the U.S. indicates that most educators also want to teach media literacy and that most students want media literacy instruction but are not receiving it (or don’t realize they are). A brand-new 2026 study by Media Literacy Now notes that many states are developing policies “alongside debates over student phone use, social media restrictions, and artificial intelligence.”

“Rather than focusing solely on limiting access, an increasing number of states are pairing restrictions with instructional requirements, directing schools to teach students how media systems, algorithms, and platforms work, and how to evaluate information critically,” the report notes.

However, the report also finds that meaningful support for policy implementation is often lagging:

“While the policy momentum is strong, the report also identifies a growing gap between legislation and classroom implementation. In many states, teacher training, curriculum guidance, and funding have not kept pace with new mandates. As a result, schools are often expected to implement media literacy instruction without clear standards, sustained professional development, or accountability structures, even as student and public support for media literacy education remains high.” (Source)

As state legislatures increase their attention to questions of media literacy, several questions are raised:

- Are schools and districts staffed and equipped to provide teachers with media literacy instruction?

- Do educators really want/need help starting to teach it?

- Are policymakers simply appealing to popular sentiment or are they committed to funding a comprehensive media literacy program?

Then there’s the problem of definition

In my work I find that educators frequently misunderstand what “media literacy” is exactly. (Some in the mainstream media misuse the phrase when they actually mean news literacy or digital literacy, or information literacy.)

On my website, the Media Literacy Clearinghouse, I define media literacy (from my POV as an educator) as “applying critical thinking and viewing skills to all media messages.” That can include advertising, visual imagery, motion pictures, video games, social media, chatbot-produced content and more. The key element is whether we examine media using critical inquiry questions, which I have written about in many past MiddleWeb articles.

Many schools do provide media literacy instruction, but educators may not call it that or recognize that’s what they are doing. For example:

- A school librarian who demonstrates “lateral reading” shows students how questioning sources is vital in the 21st century.

- A social studies teacher who explores how the Nazis used propaganda to convince people that Jews were the reasons for Germany’s problems, demonstrating how words and images influence public opinion.

- Literacy educators who read a “picture book” to students may utilize questions while they read to show how important visual literacy is in reading and comprehending illustrated content.

- Any arts educator who decides to guide students through the deconstruction of an historic or iconic photo or graphic image is also demonstrating how to both analyze as well as infer/deduce meaning through images.

- An ELA teacher using a film like “To Kill A Mockingbird” has opportunities to teach “film language” by pointing out how costume, lighting, sound and set design are designed to be read, like a book.

- A math educator who might use the occasion of the annual Super Bowl football game to engage students in a study of the costs of those 30 second commercials and why advertisers may spend up to $8 million per spot.

Are you one of those educators who has already dipped their toes into some aspect of media literacy?

Years ago, when I began teaching media literacy as a consultant, it was clear to me that I needed relevant examples that educators (and students) could instantly recognize and be familiar with.

So, a toy commercial (recorded from TV prior to the Christmas holidays) became fodder for a lesson to help students see through some of the deceptive practices often used to make things “look better than they really are.” At the same time, I would challenge students to brainstorm the answer to: who would you write to in order to complain about a toy seen on TV?

During the election campaign season, using any of the various politician’s TV ads was another opportunity to help students understand how words, images and sound combine to make persuasive and influential messages – which may fool unsuspecting voters who are susceptible to appeals to emotions, prejudices, calls to patriotism, etc.

An ad for pizza, from a magazine aimed at children, gave me the chance to explore how advertising targets specific audiences as well as guiding them through how words and images persuade (and appeal to our taste buds).

Does any of this sound doable or adaptable in your classroom?

Ideas for a Weekly Media Literacy Lesson

Here are some suggestions that you can easily adapt to your particular students or subject area. You’ll note that I’ve included a few mentions of artificial intelligence. Given the rapid expansion of AI tools that make it easy to “fake” just about anything, some AI discussion can figure into any of these ideas.

► Have students bring in one news story from their TikTok or other social media feed. This provides an opportunity to discuss source evaluation and reliability.

► Task students with bringing in a photo (or other image) from their feed that they suspect has been AI-altered. A rich lesson will involve having students say specifically why they suspect it might be altered. (Did they take the time to verify the image or fact check it?)

► Task students with bringing in a photo (or other image) from their feed that they suspect has been AI-altered. A rich lesson will involve having students say specifically why they suspect it might be altered. (Did they take the time to verify the image or fact check it?)

► Have students bring in the cover of a magazine, preferably one from a family member, for a visual literacy deconstruction. Use questions like who is the audience, who is likely to advertise in it, why do you think it appeals to your parent and/or grandparent. (Students might also create a cover using Canva or AI tools where they apply principles of persuasion).

► Task students with downloading an opinion or op-ed piece on a subject of their choosing. They should be asked to identify if bias exists and how the writer uses words or phrases that demonstrate persuasion or influences the reader to think one way or another.

► Assign students a lengthy news story (examples from the New York Times are particularly good) and have them create a tweet (280 characters)…how did they determine what to prioritize/summarize and why?

► Ask students, “What’s your favorite movie and be prepared to discuss a favorite scene from same?” This activity is one of my favorites. Students love to describe why a particular film (or scene) is memorable.

Media literacy can fit in just about anywhere

Educators across the curriculum have many opportunities to introduce media literacy activities and “healthy skepticism” to students, especially at a time when it seems that EVERYTHING online and in social media has been manipulated in some way. Just about any lesson can be adapted to include a media literacy moment. And given the current crisis around what’s real and what’s true, I feel justified in urging you to do just that.

To aid educators, I recently created the web page Students Should Know, a curated collection of brief media literacy-related videos (divided into categories) that I believe could be used to jump start media literacy instruction, discussion and research. You’ll find videos exploring advertising, agenda-setting, algorithms, artificial intelligence, bias, clickbait, confirmation bias, conspiracy theories…and those are just the A’s, B’s and C’s. I hope you’ll check it out.

Other resources:

How Can I Be a Critical Consumer and Creator of News and Media (a Common Sense Media curriculum)

The News Literacy Project: Rumor Guard (here’s an example)

Pew Research Polling: What Americans Think (numerous topics)

Snopes Fact Checks (the original and still one of the best)

For 10 years, media educator Frank W. Baker contributed columns and blogs to MiddleWeb about media literacy. He is also the author of Close Reading The Media – a publishing collaboration between MiddleWeb and Routledge/Eye On Education. He can be reached at fbaker1346@gmail.com. Visit his extensive media literacy website here.

Frank has been recognized for his many contributions to media literacy. In 2019 UNESCO honored him with the Global Partnership Alliance for Media & Information Literacy award for his lifelong work. And in 2025 he received the Elizabeth Thoman Service Award for life achievements from the National Association for Media Literacy Education (NAMLE).